One looks at you with a hardened stare. Another has a wistful twinkle through his glasses. The next appears nervous, avoiding eye contact.

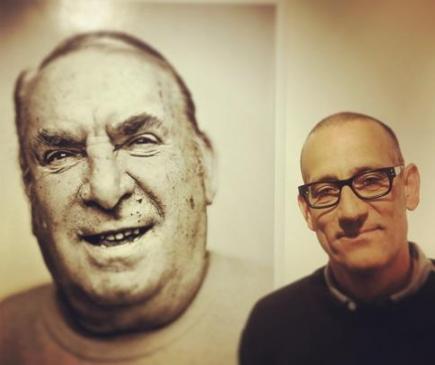

Your commute to work on a crammed tram this is not however. Brought to life by German photographer Oliver Soulas, When We Were Kings is an exhibition of cycling legends from the 1940s-80s using modern-day portraits which was launched last Friday in Manchester.

PEAS IN A POD: Soulas with his favourite of the legends, France’s Raphaël Géminiani who turns 90 this year

Soulas chose cycling giant Rapha, who opened their latest of seven worldwide clubs in St. Ann’s Square last September, as the venue to unveil his hidden treasures. He was glad he came here, if a little chastened by the cold.

“I’ve just seen a guy in a t-shirt and shorts. People here are crazy and wonderful!” he said enthusiastically at the launch as the frost began to settle outside.

Meeting people and getting on with them is what Soulas is all about but some of the old pros he interviewed for his project were not perhaps as friendly or open as he’d hoped. A few didn’t want to change into an old cycling jersey.

Nonetheless, his perseverance, and a bit of luck, took him much further than he originally intended: what started as a meet up with the 1966 road race world champion and 1962 Vuelta a España winner Rudi Altig (which Soulas hoped would lead to interviews with four or five German cyclists) swiftly became a European odyssey thanks to the matter-of-fact German.

When Soulas had wound up the interview two years ago, Altig asked: “Do you need anything else?”

Soulas was stumped. “I don’t understand, sorry.”

Same question from Altig, same response from Soulas. So Altig elaborated.

“Do you need contacts for other riders?”

Soulas did a little jig inside, said that would be really kind and before he knew it Altig was on the phone to Felice Gimondi, one of only six riders to have won all three grand tours (Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a España), 1984 Giro d’Italia and 1977 world champion Francesco Moser and Sigi Renz, who placed first in the 1963 German national road race.

The dream was born, presenting Soulas with the opportunity to interview 12 former pros born between 1925-1952 for the When We Were Kings exhibition which also features countryman Jan Ullrich, a relative youngster who retired as recently as 2007.

MM met Soulas at last week’s launch and having listened to him explain his work to a captivated audience, walked around the room with the photographer and asked him what first sprung into his mind when he stood in front of each portait.

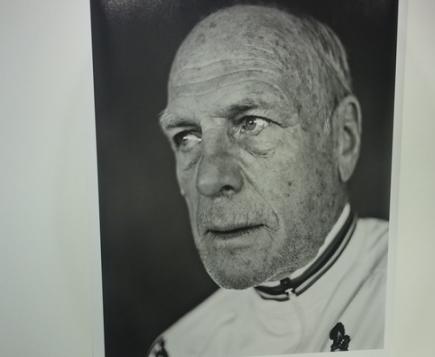

Rudi Altig. Interviewed in February 2013 in Sinzig, Germany. Born 1937.

RAPID FIRE: Altig was no nonsense on the bike and still adopts a military manner to his life

Soulas: He made everything possible. He’s very honest.

Altig is like a Prussian army general. He answers questions like a marksman: direct and no messing around. Altig still remembers the 1965 world championships when he let Briton Tom Simpson take the lead on the closing stretch. It cost him a lot of money but he says he’s still content with his lot. Winning the title the following year was of course an enormous highlight.

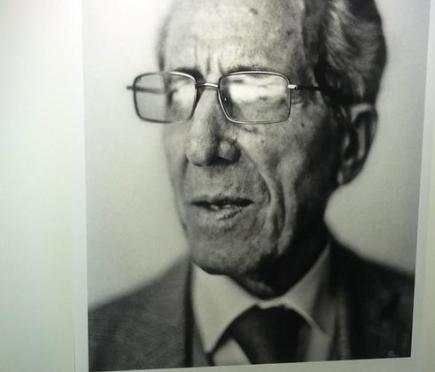

Gustav-Adolf ‘Täve’ Schur. Interviewed in January 2013 in Magdeburg, Germany. Born 1931.

COMMUNIST EUTOPIA: Schur says the world has been worse off since the end of far-left rule in Germany

For Schur, paradise is communism. His world became dimmer with the downfall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But that’s not the only thing collapsing for the German. It saddens him that there are fewer and fewer birds flying around every year and he wants people to stop destroying the planet.

Soulas: ‘Täve’ is a nickname for Gustav-Adolf, because he doesn’t want to be called Adolf due to Adolf Hitler. He’s very intelligent but I think he lives completely in the past and he can’t arrange himself living outside of communism.

Francesco Moser. Interviewed in March 2013 in Trento, Italy. Born 1951.

DON’T STOP MOVING: Moser regularly braves cold temperatures to cycle and ski

Soulas: He was berating me but afterwards it turned out he had tourettes. He was controlled but not unfriendly.

Cycling changed Moser’s life, the Italian acknowledged. The pair met as Moser removed a doorframe with a hammer and chisel in the freezing cold snow.

“One always has to keep moving, keep working,” Moser told Soulas.

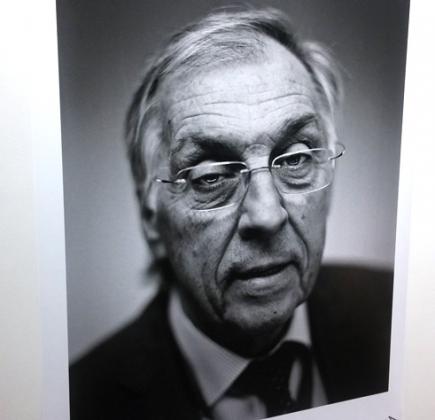

Felice Gimondi. Interviewed in March 2013 in Bergamo, Italy. Born 1942.

STEAK FOR BREAKFAST: Gimondi preferred to reminisce about his cycling career rather than talk about present day

Soulas: When he enters the room, he’s an appearance. He’s a very impressive person.

So when Gimondi speaks, you listen. Pay attention parents: the Italian’s advice is to sign your children up to play sport. Once you’ve done that, sit back and watch. No pushy parenting.

“The riders are living in the past though,” Soulas said to his Manchester audience, using an example in conversation with Gimondi to highlight how much.

“When I asked him what he ate for breakfast, he replied: ‘When I was riding we would have steak for breakfast!’”

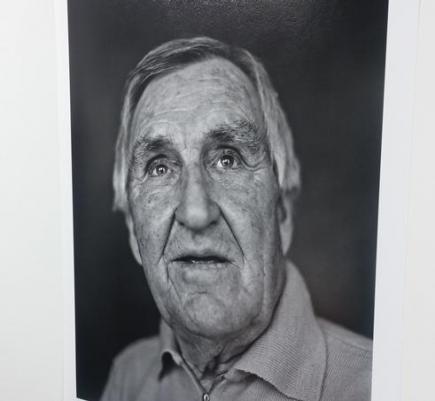

Joop Zoetemelk. Interviewed in April 2014 in Meaux, France. Born in the Netherlands, 1946.

ROOFS OVER HEADS: In another life Zoetemelk would have been building wooden roofs

“That was tough,” was Zoetemelk’s response when Soulas finished the interview.

Soulas: His eyes were very fast moving, he was friendly but shy. I got the impression he wasn’t very comfortable.

On a bike however and the Dutchman was certainly at ease. Cycling was his way out of a career building wooden roofs.

“It’s been a lovely life. It was hard too. But only the lovely images remain,” he explained to Soulas.

Freddy Maertens. Interviewed in Roeselaere, Belgium in November 2013. Born 1952.

FRIENDLY JOKER: Maertens teased Soulas that the fee to interview him would be 250 euros

Soulas: He first asked me for 250 euros. So I said ‘I haven’t come all this way just to portray you.’ So he said ‘Ok, 200 euros.’ He did me a discount! (Soulas laughs) No in all seriousness he was very friendly and in my eyes he said some really important things.

For example, when asked the question “Complete the following sentence: Life is…” he paused for thought and replied “Work.” The Belgian added that without grit and the will to win every time you would never cut it as a professional cyclist.

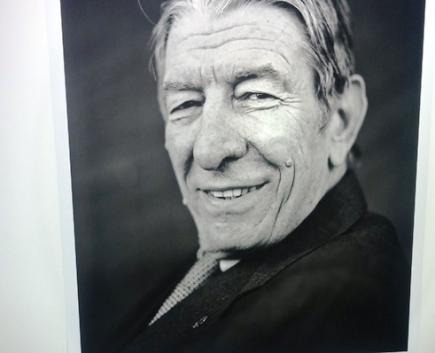

Roger De Vlaeminck. Interviewed in November 2013 in Kaprijke, Belgium. Born 1947.

LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL: De Vlaeminck’s outlook is bright despite a melancholic look

Soulas: When I told him about Freddy Maertens he brought me homegrown potatoes as a present. He also gave me a recipe, how to cook them in a Flemish way with apples and sausage. It wasn’t very good, I failed to cook it the right way (Soulas chuckles).

De Vlaeminck remembers his 1975 Tour de Suisse heroics when he beat off the challenge of Merckx. “Beautiful” was how he finished the sentence “Life is…”

He said he’d be a lion if he could be an animal. “Roar! I’d eat deer” was his response. Yet despite this frivolous way about him, Soulas also detected a different emotion.

Soulas: He looks a little bit sad. He looked straight at me.

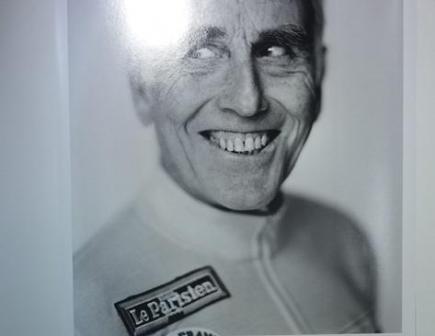

Federico Bahamontes. Interviewed in March 2014 in Toledo, Spain. Born 1928.

BIG ENGINE: Bahamontes became the first Spanish Tour de France winner in 1959

“Come to the garage,” the Spaniard told Soulas when he arrived outside Bahamontes’ apartment for the interview. But Soulas had no idea where it was.

The 1959 Tour de France winner was only 20 metres away but the comic introduction carried on before Soulas, finally, was able to meet the man who became the first Spanish winner of the Tour.

Soulas: The first thing he showed me was his Mercedes. I thought ‘So what?’ He still lives in 1959.

“There’s never been a bigger celebration,” is how Bahamontes remembers the moment that put Spanish cycling on the map. “The bells rang in 14 churches.”

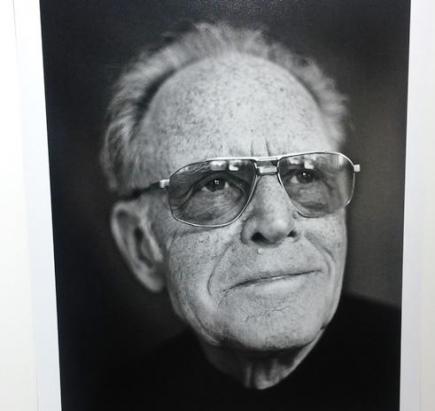

Sigi Renz. Interviewed in April 2013 in Munich. Born 1938.

RUNNING ON EMPTY: Renz is a self-confessed ‘airhead’ and was sadly never very frugal throughout his career

Renz spoke fondly of Eddy Merckx, echoing pretty much all of the 12 legends’ answers to Soulas’ question of “Best rider ever?” Renz said no one like Merckx will ever be seen again and despite stories of his egoistic ways, he was a gentleman at heart.

One time in Dortmund Merckx tested Renz’s shoes then told his German friend about his own cobbler, in Milan. So the Belgian told Renz to trace his feet on some paper and six months later Merckx presented Renz with two pairs of shoes.

Those were undoubtedly happier days for the German. Now, Soulas says, there’s a sadness even though Renz invited his compatriot to a meal of wild boar in the tennis club afterwards, a wild boar that Renz had shot himself.

Soulas: In his time he was driving a Porsche instead of saving money, and now I don’t think he has a lot of money to spend. He looks back with a tear in the eye.

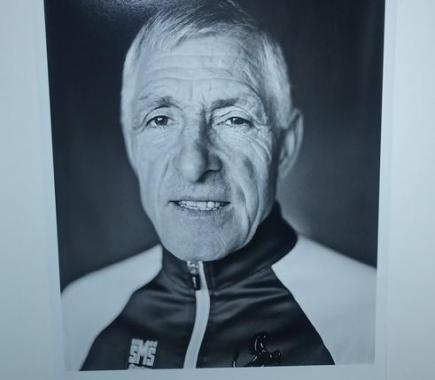

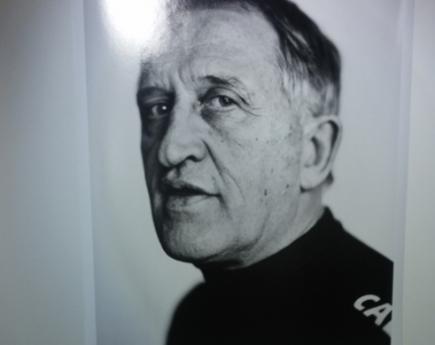

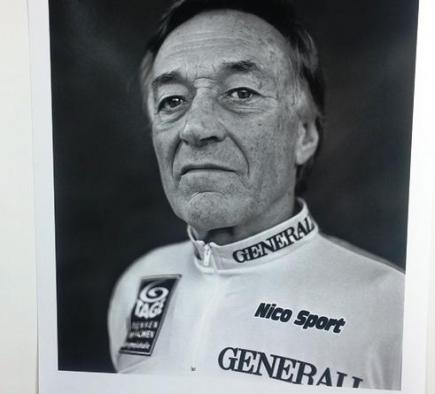

Hennes Junkermann. Interviewed in February 2013 in Krefeld, Germany. Born 1934.

MAN OF STEEL: Even approaching his 80s Junkermann estimated he was cycling around 25,000 kilometres a year

Junkermann defies his age, cycling approximately 24,000-25,000kms a year. So he knows what it’s like to simply keep on riding.

Sadly he witnessed the worst thing possible as a competitor in the 1967 Tour de France, when Simpson did exactly that, costing the Briton his life. Simpson refused to stop riding – his manager put him back on the bike – when suffering from heat exhaustion on the notorious Mont Ventoux and he was later found to have drugs in his system.

Soulas: Hennes told me putting Simpson back on the bike was the worst thing they could do. He was 100 metres behind and saw the whole thing. It was a sad story.

Patrick Sercu. Interviewed in November 2013 in Ghent, Belgium. Born 1944.

MAN’S BEST FRIEND: Sercu spoke of his soft spot for dogs. He has a labrador

Soulas: He was the perfect gentleman, I liked him a lot. He’s the best track rider ever and Eddy Merckx’s best friend.

The pair met at the famous Six Day Race in Ghent. Befitting Soulas’ ‘gentleman’ description, Sercu snuck the German into the iconic Belgian velodrome for their chat and gave Soulas a ticket to the race afterwards.

“I have a labrador,” said Sercu, replying he doesn’t want to be an animal when asked. “He’s so sweet and smart.”

Sercu was no puppy-eyed pushover though. At the 1977 Tour de France, on a stage from Roubaix to Charleroi, he rode nearly 200kms out front alone. “All of Belgium still remembers,” he recalled to Soulas. “No one ever expected I would win.”

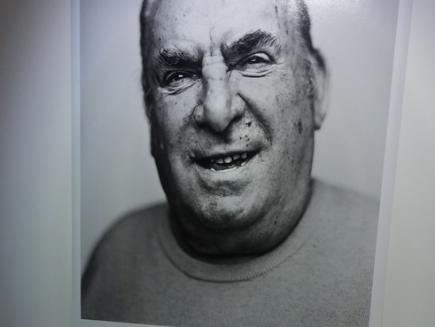

Raphaël Géminiani. Interviewed in April 2014 in Auvergne, France. Born 1925.

WINE, BEER OR CHAMPAGNE? Visit Géminiani and don’t expect tea or coffee

Everyone has a favourite. You can pick yours from this eclectic crew but, for Soulas, the Frenchman left the biggest impression when they first met on a spring morning.

Soulas: It was 10am, he opened the door with a cigarette and he offered me either wine, beer or champagne. I said ‘It’s too early for that!’ and he replied: ‘It’s not alcohol, it’s champagne.’

He was joking of course but yes, he was very humorous, clever and open-minded even though he’s 90 years old.

“We have everything we need, everything. It’s fantastic,” said Géminiani, pondering where he thought ‘paradise’ was.

“Paradise is here on earth.”

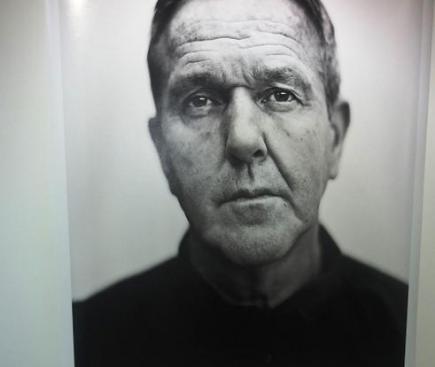

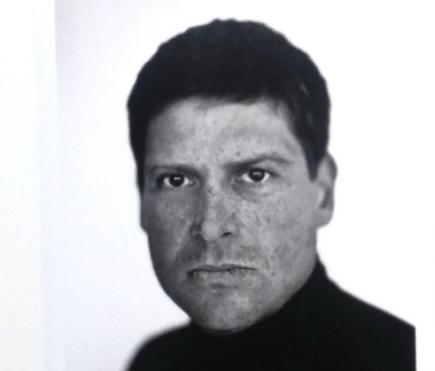

Jan Ullrich. Interviewed in November 2014. Born in Germany, 1973.

WILD ANIMAL: The fixed stare of 1997 Tour de France winner Ullrich, who later confessed to doping

Ullrich is Soulas’ most recent interviewee and by far the youngest of the bunch. The German won the 1997 Tour de France but in 2013 he confessed to doping during his career.

Nonetheless, just a brief encounter with the former Olympic champion was enough for Soulas to differentiate between average humans and elite athletes.

Soulas: I thought he was a relaxed, smooth guy, but he’s not, he’s tense. Friendly though.

His eyes were like a wild animal. Maybe you need to be the opposite of relaxed and laid back to be world class.

Funny Soulas should say that, because his exhibition is exactly the same: staring at these old pros can be a bit uncomfortable, but their allure is undeniable.

PAST GLORIES: When We Were Kings looks back at old pros’ lives while taking a look at their current existence

For all the ghosts of cycling’s past, the often uplifting tales from Soulas’ mission to not only photograph these old heroes but also spend time with them is heartwarming.

His next stop? The great Eddy Merckx, he hopes.