In 2018, a raft of public figures including the female Prime-Minister at the time, Theresa May, payed tribute to the 100 year anniversary of women gaining the right to vote.

However, the determination which saw the Representation of the People Act finally passed over a century ago hasn’t necessarily become obsolete in 2021, and as Channel 4 anchor Cathy Newman warned: ‘history still needs to be made’…

Fighting new battles

Although a landmark victory, the bill which allowed women to vote was only applicable to 43% of the adult female population who fulfilled certain conditions.

These included those over 30 and married to men who occupied a property which charged over £5 per year, or University graduates.

It wasn’t until ten years later, in 1928, that all women over 21 were granted votes on the same conditions as men, as part of the Equal Franchise Act.

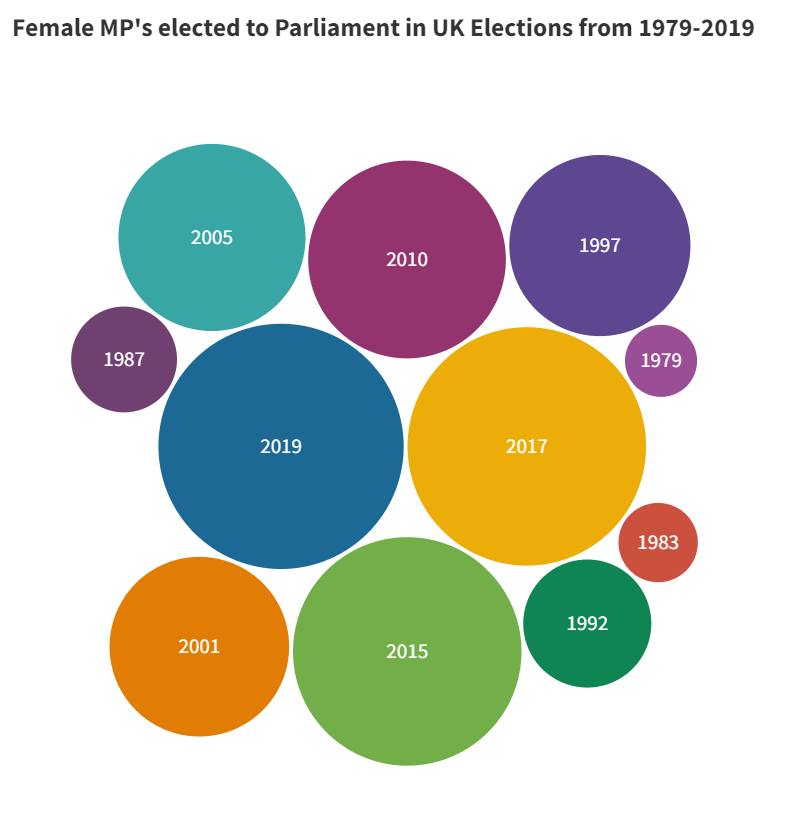

It would be easy to assume that the struggle ended there. However, 93 years on, women still only make up 33.8% of Parliament.

This figure has significantly improved from a low of 2.9% 40 years ago, when the 1979 parliament saw just 19 female MP’s making up the 650 in the commons.

Rachel Sills, from the Pankhurst Centre explained why closing the representation gap has been a slow process: “There are barriers which are invisible to women entering politics, such as living away from home. Women who do stand are prone to the ways in which maternity is not set up for them in parliament.”

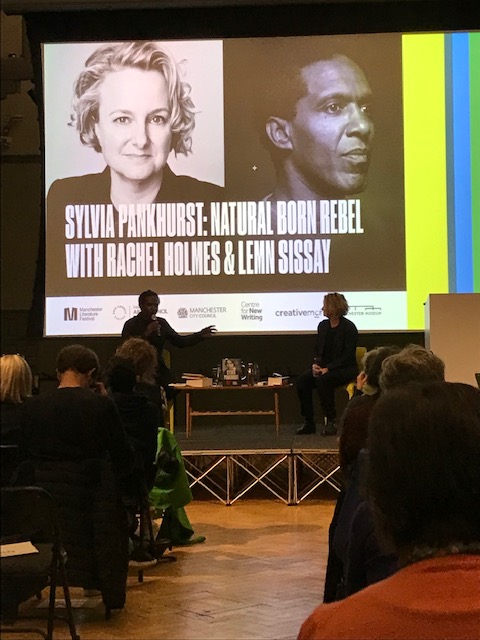

Talking about leading suffragette figure Sylvia Pankhurst at last month’s Manchester Literature Festival, author

Rachel Holmes pointed out that she was particularly passionate about supporting maternity services. Indeed, Emmeline’s second daughter wrote a book entitled ‘Save the mothers’, which was published in 1930.

The law states that female MP’s are currently entitled to full maternity pay, but a ‘locum’ replacement stands in as a replacement, restricting them to consistency business. The fact that these replacements are not allowed to take part in Common’s debates or votes led Stella Creasy, Labour MP to allege in June this year that voters could be discouraged from voting for candidates of childbearing age.

In February 2021, Suella Braverman, a Conservative attorney general, became the first cabinet member to take six months off on full maternity pay. This was thanks to the Ministerial and Other Maternity Allowances Bill, passed in February, which meant that cabinet members wouldn’t have to step down from senior positions when taking maternity leave.

Deeds not words

Take a walk down Peter Street and you’re amongst history. In 1905, the newly formed Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU or suffragettes) interrupted speakers at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. This was the first of many more radical acts they would go on to commit, as part of their motto ‘Deeds not words’. Vandalism became a regular tactic, with churches, politician’s houses, railway stations and public buildings having their windows smashed or set alight.

Back at the Pankhurst Centre, Sills explained why they felt the need to intensify their campaign: “I think they became desperate, they felt that extreme measures were needed if extreme matters required attention.”

She considered: “It polarises people, but at least it attracts attention to the cause.”

Holmes also reinforced the view that creative design was crucial to the suffragettes’ news presence: “The artist was the activist, and the activist was an artist. The artist performed so the activist could gain attention to their cause.”

This narrative seems familiar. In a Radio 4 interview in April 2019, Extinction Rebellion member Clare Farrell said: “The press want the drama, they’re not interested unless there’s a lot of disruption and people get arrested. Then, it starts a conversation.”

If this is the case, then does causing chaos with the intention of highlighting a cause mean that there parallels with the suffragettes and their environmental descendants?

The 21st Century suffragettes?

In September 2020, Labour MP Diane Abbott told Sky News that Extinction Rebellion were “protesters and activists in the tradition of the Suffragettes.”

It follows multiple comparisons from eco-campaign group members to female suffrage in the twentieth century. Even Sills told me: “I think people are more interested in the suffragettes today with movements such as environmental movements”.

Indeed, a stunt led by Extinction Rebellion involving the smashing of windows in London’s Canary Wharf saw them wear the suffragette’s famous green, white and purple rosettes and hold posters displaying the message ‘Better broken windows than broken promises’.

Although many model themselves on the plight of the suffragettes, are they justified in undertaking similar methods?

Logic suggests that any activist group could justify disruptive behaviour by making the same comparison, and it should be noted that other campaigns such as the smoking ban, no-fault divorce or exiting the European Union didn’t rely on vandalism.

Esme Finch is the director and founder of Enviro-Matters, a storytelling and dance enterprise which aims to inspire children to value the natural world. She explained to me that she believed environmental movements have a distinct affinity with the suffragettes and supports their actions: “Extinction rebellion is the prime example of comparing suffragettes to environmental campaigners and yes, I think women or any protestors are justified in their right to protest for the future of our planet.”

An author herself, Finch was able to offer another angle on the comparison, contending that 80% of people women are affected by climate change are in fact women: “In the global south, women have traditional duties such as walking to get water or taking care of farmland, heavily reliant on weather, so if there’s a drought they’ll have to walk much further.”

This coincides with Alok Sharma, President of the COP26 Summit, announcing last Thursday that “gender and climate are profoundly intertwined” as well as a heavy emphasis on the relationship in the United Nation’s Development Programme.

But would the suffragettes be proud of today’s crusaders donning their colours?

Back at the literature festival, Holmes insisted that Sylvia Pankhurst believed she couldn’t separate out social justice and women’s equality: “She thought that if you’re not going to give votes to working class women and men then it’s not worth having!”

Having explored this, it’s not difficult to imagine the suffragettes of yesteryear getting behind today’s movements, although to what degree remains open to speculation.

‘No taxation without representation!’

One glaring difference between the suffragettes and today’s eco-groups is that women in the 20th century didn’t have the basic right to vote. People now can freely choose to vote for parties adopting environmental change, such as the Green party, and accordingly, their vote share rose from 1.1% to 2.7% in the 2019 election.

However, despite pulling in 865,715 votes, the Greens are only represented by one MP in Parliament, owing to our first past the post system.

To Finch, this justifies the insurgency conveyed by current environmental campaigners: “We can’t wait for the votes to come in to hope for a government to act, we are creating our own grassroots movements and uprising anyway.”

Finch also confirms that she supports proportional representation as this would give Green MP’s a greater say in Parliament.

The suffragettes, and within this, even the Pankhursts themselves were not affiliated to one political party, proven by the fact that Emmeline stood for the Conservative Party and Sylvia was a devout socialist.

To the Pankhurst Centre’s Sills, this epitomises the very concept of free will that the women were fighting for: “The whole point was freedom of choice so they could vote for whichever party they felt best.”

So, even if the suffragettes had been divided over the issues surrounding climate change in the present day, reforming the way in which we vote now may still have been a high priority.

Back to basics

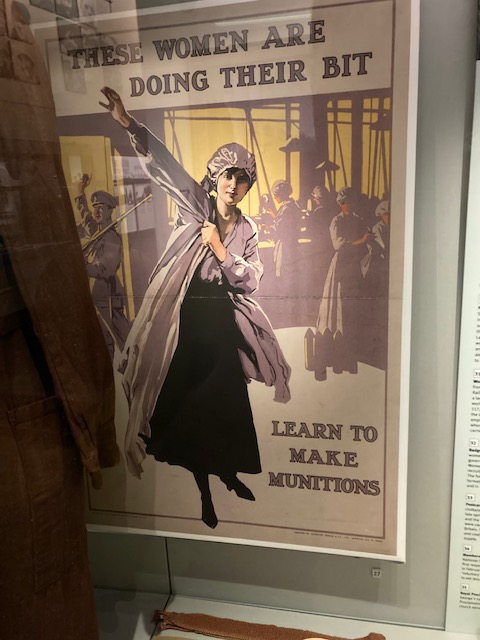

Not all historians agree that the suffragettes’ success can be attributed to their radicalisation. Indeed, there are many who believe it was their contribution to World War I which saw them rewarded with achieving the vote.

Following the suffragettes’ suspension of their campaign activities, the outbreak of war saw as many as a million women sign up to work in munition factories, and 23,000 join the Land Army.

Writing in BBC History Revealed Magazine, Dr Diane Atkinson argued that women fulfilled an essential role in public life left by men who were away fighting that it afforded them a moral right to vote: “When the war was over, nobody in their right mind could say that women didn’t deserve the vote.”

Throwing their weight behind this to keep the country going was a significant change of direction by the formally antagonistic, antisocial suffragettes, and it immediately won them their victory as soon as the war came to an end.

This begs the question: Is campaigning through legal channels rather than vandalism something which the suffragettes would adopt now?

Adam Peirce, 35, from Climate Emergency Manchester illustrated why his group is approaching the issues surrounding environmental sustainability differently to Extinction Rebellion:

“You’re always going to get people who believe that radical tactics such as getting themselves arrested are needed but we think it’s more effective to go through the democratic process.”

Peirce explained: “Larger, deeper, movements and a consensus is needed to enforce real change”.

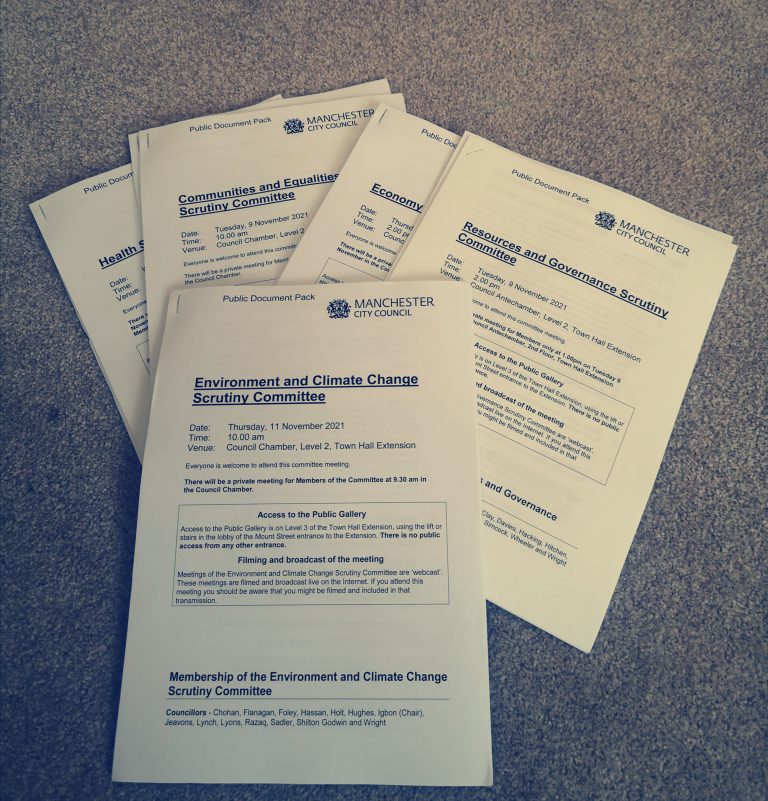

Climate Emergency Manchester’s have achieved a rare triumph, successfully initiating a dedicated Environmental climate change scrutiny committee in Manchester City Council.

Getting enough signatures to petition the Council, as Peirce explains, has granted them a speaking slot where they can hold them to account: “Name one other activist group who’s managed to get a constitutional change in the council.”

The group are using this platform to contribute to policy making, with an emphasis on more devolved local democracy through neighbourhood planning.

When quizzed on which approach has the most effective legacy, Sills somewhat sat on the fence: “It’s hard to tell, people have their allegiances. That’s why there were suffragettes and suffragists.”

However, she did add: “Part of giving women the vote in 1918 was that they didn’t want Government action to continue.”

So, perhaps there’s a time and place for the radical activism adopted for the suffragettes after all, not only for getting the message discussed, but for pushing its urgency.

Are groups such as Extinction Rebellion or Insulate Britain indirectly helping lawful groups to gain support, as more people become aware of their importance? Peirce considers: “I think activism is a spectrum, it isn’t black and white. Although I don’t condone them, I can understand their tactics tactics as it drives the notion that this isn’t business as usual and people have to wake up to that.”

Off limits

Peirce also shared that he didn’t support the decision by some members of Extinction Rebellion to block the distribution of certain newspapers in September 2020.

This incident stands out as an aperture in the equating of suffragettes and today’s eco-campaigners, as the suffragettes relied on media to spread their message, also printing two publications of their own; The Suffragette and Votes for Women. However, Peirce is clear that he is against censorship, and would instead like to see more accountability by some journalists to report climate change truthfully.

Another key difference which potentially diverges from the suffragette legacy is the aims of environmental campaigners to place limitations on the population consumption.

Sylvia Pankhurst is quoted as saying “We do not preach a gospel of want and scarcity, but of abundance… We do not call for a limitation of births, for penurious thrift, and self-denial. We call for a great production that will supply all, and more than all the people can consume”.

The think tank Policy Exchange claimed in 2019 that groups such as Extinction Rebellion seek to ‘impose full system change to the democratic order’ by means of extremism.

Whilst the suffragettes may well also be labelled as extremists today, it remains true that they did advocate for increased democracy.

When asked whether there should be a referendum to ask the population whether they want a net-zero carbon strategy adopted, Peirce argues that this would be too simplistic: “I can’t see it being productive. People are far too polarised to have nuanced debate between them.”

He adds that a Citizen’s Assembly would offer people the chance to democratically make an informed decision on our environmental future, as detail would be lost in a binary referendum.

So should we liken Insulate Britain activists stepping out in front of cars on the M25 to that of Emily Davidson throwing herself in front of a horse at the Derby in 1913? Would the suffragettes be proud of today’s eco-activists or would they take lessons from their more co-operative approach which helped them achieve the vote after the war?

Have your say at @mancunianmatters

Join the discussion

A highly interesting thought provoking read. The best article I’ve read in a while .