Molotov cocktails streak across the night sky. Tear gas hovers just above the ground. Hong Kong appears on the brink of collapse.

In the special administrative region of China, protests aimed at thwarting an extradition bill have morphed into a six-month-long conflict, verging on civil war.

On one side, supporters of the government’s nationalistic agenda, presided over by Chief Executive Carrie Lam. On the other, students, office workers and public servants who regard Hong Kong’s autonomy as sacrosanct.

Far away from the city’s frontlines, tens of thousands of Chinese nationals arrived in the UK for school and university during the autumn – with higher-education attendees topping 120,000 in 2018.

Mirroring the dissonance abroad, across Britain, a schism has developed between protest sympathises and their local pro-government counterparts.

‘We were all afraid’

In the North West, where almost 6000 Chinese citizens currently attend the University of Manchester – the highest number of any European educational institution – confrontations have intensified.

On September 29, overseas Hong Kong students staged a mass “anti-totalitarianism” demonstration, broadly unopposed. By October 1, China’s national day, animosity flared between themselves and a nascent rival faction.

“We were doing a ‘people chain’ near the University of Manchester,” explained Ryan (not his real name), a member of Manchester Supports Hong Kong.

“When the Chinese people saw us doing some protesting, they found someone to shout at us on the opposite side of the road… Then it escalated to 200 or 300 [counter-protesters], totally outnumbering us.”

As they moved to a different location, closer to the city centre, the counter-protesters followed. Soon, the city’s streets echoed with motifs from the struggle – one group yelling “Two systems!” while the other responded “One China!”

Along the way, members from opposing sides almost came to blows. “They tried to assault some of us from behind,” Ryan says. “They kept on following us, even though we tried to avoid conflict.”

Two weeks later on Oxford Road, one of the city’s main arteries, the two groups faced-off again: the pro-democracy protesters clad in black; the pro-China activists brandishing bright red national flags.

Eggs were thrown from a fifth-floor window, narrowly missing members of the Hong Kong community. “Pretty lethal, if they had better aim,” one anti-government protester quipped.

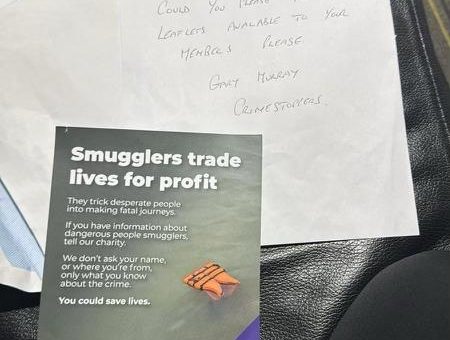

But in a more disturbing development, counter-protesters targeted Hong Kong students with surveillance equipment, sparking fears of retribution.

“Mainlanders would take close-ups of our faces and post them on social media,” a protester wrote, who wished to remain nameless.

“We were all afraid of the threats of ‘white terror’ and media violence if we were recognised.”

Later, another complained about “anonymous cyber-harassment”.

“It has caused me a lot of anxiety, and I am constantly looking over my shoulder when I’m on campus,” they wrote.

Others said they are now wary of openly expressing their views at university.

“When I’m on campus, I have to speak carefully if I am discussing or explaining the current issue in Hong Kong in order to avoid being targeted by the mainlanders, as threats have been made across social media,” they wrote.

‘I had to protect Hong Kong’

In a nondescript Manchester café, I meet Hiro (not her real name), who gave two speeches at the October 13 demonstration.

At the start of June, she was living back in Hong Kong. “That was when all of the things started to get worse,” she says. “The police started to use more force, more tear gas, and then more people got involved.”

At first, Hiro attended street demonstrations intermittently, assuming they’d soon fizzle out. But as police violence and arrests of protesters rose, so did her support for the pro-democracy cause.

“I never really wanted to get involved,” she admits. “But then I thought ‘Hong Kong’s my only home – that’s where I was born, I grew up in that place – and it’s very important for me to, you know, protect it.’”

For her, a mass attack against pro-democracy supporters on July 21 was a key turning point.

After a day of marches, gangs of white-shirted men, rumoured to be triad affiliates, stormed Yuen Long station, where they corralled, intimidated and bludgeoned those trying to board trains.

“It was crazy because I live nearby to that area,” Hiro says. “Sometimes I go out in the middle of the night, and I come back home quite late, and if I was the one being attacked by the mob in the subway, I would be so scared.”

In total 45 people were injured, including two of Hiro’s friends. But alarmingly, the police stayed away until the attackers left, fuelling belief the government was pursuing Chinese patriotism over protesters’ welfare.

“They’re supposed to protect citizens, but they weren’t doing their job,” she says. “That’s when I realised it was a very serious problem.”

A new front line

Despite her fervent activism, Hiro continues to operate in secret. She doesn’t just fear the ire of the Chinese authorities, but also acrimony with her parents. Her father is a committed government supporter.

“I don’t want to argue with them because they’re my family. I care about them, so I have to keep the balance,” she explains.

Her home life is a microcosm of divisions now found across the region. As the protests escalated, citizens severed relations with friends and businesses, often disregarding those with whom they couldn’t agree.

“What makes me feel really upset sometimes is how things got to this point, you know?” says Hiro, clearly affected.

“It’s literally like when two countries are at war. They don’t try to talk to each other; they don’t try to communicate.”

At the October 13 protests, this open hostility surfaced in Manchester. It’s disconcerting for many of those involved, and especially Hiro, who found herself on a new front line, 6000 miles from Hong Kong.

The pro-government supporters “were shouting and screaming,” she remembers, “and we were screaming back, too.

“I hated to do that because we should be peaceful. When you’re yelling at each other, you’re just having an argument. I found it very unfair.”

Today Hong Kong, tomorrow the world

Following a vigil honouring the death of pro-democracy activist Alex Chow, I meet with two members of Manchester Supports Hong Kong in the back of a pub.

The event took place on a day when a policeman shot a student, masked protesters set a government supporter on fire, and security services first tried to storm the occupied Polytechnic University.

“There are a lot of people who are having mental breakdowns these days,” says James (not his real name) of those in the Hong Kong community.

“We can’t really do much, and we are only watching the news, so today was more [about] just grieving and trying to support each other.”

Aside from this, they stress the Hong Kong protests shouldn’t be seen as an isolated incident but as part of a much broader struggle.

“What’s happening in Hong Kong is the suppression of freedom, speech and democracy,” says Anna (not her real name). “But this is not just happening in China’s territory. It’s happening all around the world.”

In October, Daryl Morey, general manager of NBA team Houston Rockets, deleted a tweet supporting the pro-democracy movement after criticism from Chinese fans and sponsors.

A few days later, tech giant Apple removed a mapping app that protesters had been using to avoid police during demonstrations, sparking further concerns about censorship.

“We are the [current] victims because we are directly controlled by the communist party,” Anna says. “But if we don’t boycott China now, then it’s not just going to be Hong Kong – it’s everywhere.”

A lost cause?

Apart from holding rallies, the group has sought talks with MPs, drawn up petitions and encouraged others to snub Chinese made goods. But it feels like a losing battle, especially in their current city.

In 2013, the then Chancellor George Osborne set up The Manchester China Forum, “a special purpose vehicle for driving forward the Manchester-China relationship”.

The group states Chinese financiers have since invested 3billion, funding the new Airport City development along with building projects in the 155-hectare Northern Gateway site, approved by the council in February.

This isn’t an isolated case, with many large-scale ventures in Britain acquiring China’s backing.

But the government has postponed a decision to allow Chinese telecoms giant Huawei to develop the country’s 5G network, amid fears it would use the tech to spy on the UK.

Anna believes the UK’s economic dependency on China will result in pervasive forms of censorship and rights abuses if un-checked.

“In the future, our hands will all be tied because businessmen will have to stand on China’s side.”