“It’s remarkable to think that an old tobacco warehouse in Chorlton-Cum-Hardy would go on to influence Hollywood.”

For around forty-five years, Brian Cosgrove and Mark Hall, who together founded the Cosgrove Hall Films studio imprint, were behind some of the most loved children’s television shows including Danger Mouse, Bill & Ben, and Postman Pat.

Following its closure in 2009, the studio had been desperately seeking a place to keep its archives of well-loved characters.

In 2017, Waterside Arts in Sale became the home of the many 2D hand drawn animations, scripts, and stop motion puppets that helped to create such fond television memories for children growing up over the years.

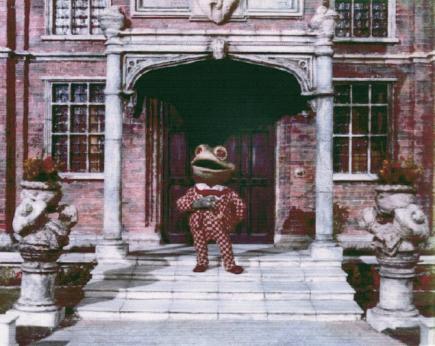

But, for almost thirty years, some particular puppets were missing from that archive. A large group of the puppets used for the main characters in 1983’s Wind In The Willows, and its subsequent television show running from 1984-87, were presumed lost following an exhibition.

Earlier this year, it was revealed the 25 puppets, made out of cast resin with metal jointed skeletons, had been kept in storage by a shop display designer who acquired them. In April, they were put up for auction – estimated to be worth around £10,000.

Now, the puppets are back where they belong with the rest of Cosgrove Hall history at Waterside and will appear in a forthcoming exhibition at the end of the year.

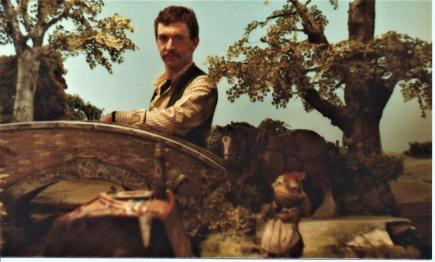

The puppets were brought to life by a team of animators, who would meticulously move each puppet frame by frame.

One of those animators was the Oscar and BAFTA nominated Barry Purves. Alongside Wind In The Willows, Barry has also worked on other children’s shows including Bob The Builder and Rupert Bear, as well as productions with directors Tim Burton and Peter Jackson.

We caught up with Barry to talk about his fondest memories working on the tale of Mr Toad and how much of an impact the film, alongside other Cosgrove Hall productions, has had on the animation world in Hollywood today.

This year marks 35 years since the Wind In The Willows TV show first began airing. How special was the film and the show to your career?

It was six years of my life. Seeing the puppet again this week has brought back all sorts of emotions. It wasn’t exactly the start of my career, but it was right at the beginning.

I think really the thing that I will always remember is Toad. He is such a gorgeous character, he’s a naughty boy that won’t grow up and he has such passion for everything he does. I think that sort of thing echoes in my career and in my life now, about not wanting to waste time.

It wasn’t a job to work on something that had such amazing production values for a children’s show. It was like the Downton Abbey of children’s television: we fussed over every knife, every plate, every detail of the costume, none of which you can go out and buy. You can’t go out and buy a nine inch suit for Mr Toad, you had to be creative so that the set looked correct on screen.

I think what was joyous was Mark Hall and Brian Cosgrove – they cared about the atmosphere on the sets, they cared about the scripts, the way things were filmed, and they encouraged you to contribute. It was very much a team effort, it started with Mark and Brian and a very good adaptation of the book.

What was the process like to film?

It was terrifying to film because we couldn’t tell what we were doing. There were no monitors to show us what we were filming.

When we were filming Wind In The Willows, we just had the sets, puppets, and a 16 millimeter Bolex camera. So, we were, in a sense, working blind in the way that Ray Harryhausen worked, you know. You just moved the puppet, took the frame, and moved the puppet again.

We started in ‘81 and the film came out in ‘83, if you think of the technology then, VHS had only just come out but we didn’t have video on set. If you moved a puppet, you moved him – you couldn’t go back.

Were there any specific behaviours or attitudes that you had to display through the animation of Mr Toad?

We had to act the characters out, which sounds like an odd way to think about it. The animators were cast as particular characters and you animated that character and nobody else did. So, basically, your qualities came out in him.

There’s a sort of osmosis, after playing a character for six years, Mr Toad starts looking like you and you start looking like him, but that’s not a bad thing – there are worse characters.

Animation is sort of like a mask that rather than hiding, reveals you. You can safely behave in a way that you can’t behave ordinarily in animation. It’s like putting on a mask, it gives you licence to be outrageous or a diva. Toad was a drama queen and a diva, and we loved him for it.

What was it like seeing the puppet again after all these years?

He is so ingrained in my hand, there’s a muscle memory that will always be there.

This is the original puppet, and this is the real one we used. My thumb feels the buttons on his suit I felt thirty years ago. That’s the joy of stop-motion, you can touch it.

It’s not about digital things, your hand was the best recorder and the performance was created in your hands, not in post-production. What you did ended up on screen.

Toad’s family motto is ‘semper bufo’, which means ‘toad forever’ or ‘always a toad’ and I think, yeah, that’s about right. After six years of working with him, he’s part of me and I’d love to revisit him somehow in some shape or form.

He is an iconic character.

He is. He’s naughty and he always gets away with it. He has a passion and heaven help us when we don’t have a passion for things, wherever it’s the countryside, cars, or caravans.

He’s a multifaceted character, selfish perhaps, but his friends love him and he loves his friends. He’s just this bundle of energy and it was such fun to animate. David Jason caught the voice perfectly.

Why do you think the story has resonated with audiences for so long?

It’s a great story about friendship and how time is slightly changing. It has that melancholy feel in it that this may be the last summer and there’s a shadow of things changing.

It’s a very profound book I think, especially about the joy of the countryside. Go and sit by the river and enjoy a picnic, do look at the birds and butterflies, while they’re still there. Get off the computer screens, mess about boats, and have the passion of Toad.

What was it like working with such an esteemed cast of actors?

What a luxury to have giants of British acting like Michael Hordern, Ian Carmichael, David Jason, Beryl Reid, and Una Stubbs. To have that quality of voice, for the series as well, not just the film, was incredible.

You can’t underestimate the power of a good voice artist and, for me, as one of the animators of Toad, David was very good and was directed to include the breaths and gasps perfectly.

Toad was vocally fussy and that was a joy to animate. To see a puppet suddenly breathe is magical. You see international animated films today where they just put a voice over a character, and they don’t always fit, but to see a puppet suddenly react to its environment or voice is exciting.

How much footage were you able to record in a day?

Because we didn’t have video, I think our schedule for a day on Wind In The Willows was that each team had to produce twenty seconds, which is a lot. We couldn’t do that today because the lighting and technology takes longer to set up. It was a case of move the puppet, click, move the puppet, click.

When I work now, I sort of have half an hour for a second of film – that’s a good schedule to work to. I was on the team that made the Twirlywoos (2015 Cbeebies show) and that was very technical, we shot about eight seconds a day. There was a lot of green screen, rigs, and technology. Again, that was a joyous shoot.

What can you tell us about the upcoming exhibition at Waterside Arts?

They’re hoping to freshen up the puppets as best as they can and have a big exhibition before the end of the year and people will be able to look at them closely.

There’s been more sophisticated puppets since, he looks a bit basic now as the whole craft of animation has developed, but it may not be bold to say that without Cosgrove Hall, you wouldn’t get these big films today.

How do you think the film and television series has had an impact on animation today?

There was nothing like it and it was influential – we started something and I think it spread. A lot of the animators and artists involved went on to work on the big Tim Burton feature films and at Laika, who did Coraline and ParaNorman, and the puppets were made by Peter Saunders, who now makes puppets for Tim Burton and Wes Anderson.

It’s remarkable to think that an old tobacco warehouse in Chorlton-Cum-Hardy would go on to influence Hollywood.

What is your favourite part about being an animator?

What I love is when a script says ‘and Toad hears a car coming and gets excited’, I think, well, he can’t hear, he doesn’t have ears like human characters so you have to find a slightly different kind of body language. I think, well that’s why I enjoy being an animator, I love the challenge.

You do face challenges, but that’s what keeps you fresh. All in all, it’s been a fun career and I’m not ready to give up yet.

Cosgrove Hall: Frame By Frame will run from Friday November 15 to Tuesday December 31 at Waterside in Sale.