The Hungarian elections will not be decided in Manchester. But, for the first time, Hungarians living in the UK could have a bigger say – if the government allows it.

Should Prime Minister Viktor Orban have his way, it won’t.

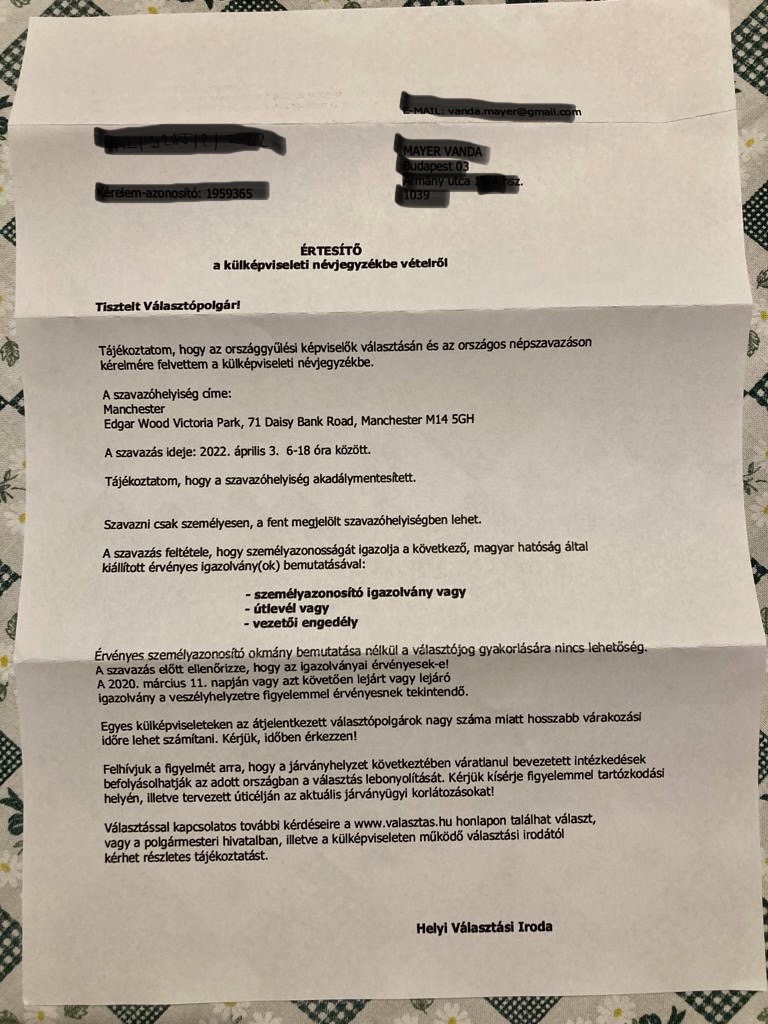

The Hungarian government has opened just three voting stations in the UK – in London, Manchester and Edinburgh – for a 190,000-strong community.

If this disengages many of the voters who would have to travel several hours and pay high costs to vote, the government might not mind – these absentee voters are likely to overwhelmingly oppose Mr Orban’s regime.

One campaign group has called for an expansion to 15 locations across the country, but the government has rejected the request.

So, Hungarians are restricted to three – an alarming number in comparison to Bulgaria’s 135 voting stations across the UK for their own national elections last year.

Endre Hann, the head of polling agency Median, has labelled the current system clear and obvious electoral fraud.

Diaspora Aid

In response to the unfair election laws, Balazs Lang, a Hungarian living in London, launched civil interest company Diaspora Aid to fight for an equal access to voting for UK-based Hungarians.

The NGO collects donations through Crowdfunder to cover transportation and accommodation costs for voters who otherwise would be unable to afford it.

It was formed by civilians for civilians, said Mr Lang.

“I’m a former producer for the BBC’s Hungarian language programme, and one of my partners is a manager with an international company,” he said.

“The other is a father who left Hungary with his daughter and a suitcase after his house was repossessed, and the fourth partner works the night shift at a crisp factory.”

The aim of the organisation is to mobilise UK-based Hungarian voters in support of their constitutional right to vote.

“That Hungarians living here can only vote in three locations – I thought something needs to be done about this,” he said.

“Because neither the government nor the opposition has done anything to help, civilians here have been forgotten – so I decided to help instead.”

Mr Lang had briefly moved back to Hungary – but he found the political environment unbearable. He returned to the UK three years ago.

Before founding the NGO, in November 2021, he petitioned the National Election Office (NEO) to open voting stations in 15 major cities across the UK with significant Hungarian diasporas.

He also called for an increase in voting stations in the established locations of London, Manchester and Edinburgh, where people complained of chaos and long wait times four years ago.

The NEO, dominated by a Fidesz majority, dismissed the request – in January 2022, NEO president Attila Nagy announced that the issue would only be revisited after the elections.

While Hungarians are limited to three locations, Bulgarians in the UK voted across 135 stations during their national election last year.

“The two countries’ diasporas are a comparable size,” said Mr Lang.

“The populations are also quite similar, and they tend to be behind us on the usual lists of shame – most corrupt, lowest GDP, basically anything bad – but they are a lot more democratic in the case of elections.

“Same with Romanians, who could vote in over 80 locations,” he noted.

Meanwhile, countries like Portugal and Lithuania enable online voting for their citizens abroad “so they can vote in five minutes over the phone”, said Mr Lang.

“In other countries, for some reason, the democratic right to vote works fine – in comparison, Hungary makes it impossible for their expatriate nationals to vote.

“And it’s because, predictably, 80 to 90 per cent of the Hungarians in the UK would vote for the opposition, so the government has no interest in helping,” said Mr Lang.

“It’s completely unconstitutional to have someone drive six or eight hours with high travel costs to vote, but they’re doing it to the Hungarians here – to discourage them from voting,” he said.

He launched Diaspora Aid to correct the injustice, despite people warning him against it.

“Everyone told me to stop doing it – it’s been tried before, and people have failed to collect less for much bigger problems,” he said.

“But we’ve already reached over half of our target, and we’ll be able to help hundreds of voters.”

Over 500 people have already donated – primarily from Hungary – and Mr Lang receives letters from many of the donors.

“Pensioners at home who barely have any money left will donate, and they’ll apologise for how little they can give,” said Mr Lang.

“If they want it to be fraud, it’s fraud”

In addition to struggling for funds, Diaspora Aid has to balance on a tightrope of complicated electoral rules – they cannot, for example, arrange transport for voters despite being a non-partisan organisation.

“We can’t do just anything, because the rules give the government complete discretion to label something electoral fraud at the drop of a hat,” explained Mr Lang.

“I could go over to the neighbour’s and offer him a ride to the voting station – and the government could say I’ve committed electoral fraud.

“If they want it to be fraud, it’s fraud.

“So we strictly collect donations from private donors and get the money to private individuals.

“Diaspora Aid is the middle-man, getting the money to voters who need support to access stations.

“We work to improve mobility – beyond that, it’s not our fault that the majority of the people we will help happen to be opposition supporters.”

Mr Lang believes that, in a working democracy, their work would be appreciated as a drive for civil freedoms.

“I would welcome support from anyone – if Mr Orban wants to thank us for doing his job for him, I would be incredibly happy,” he said.

“In a normal country, the Prime Minister would acknowledge our work – but I’m not that naïve.”

When Mr Lang launched the NGO, he hoped it would trigger a wider movement for Hungarians across the west.

He added: “We don’t want to march on Parliament – we’re just civilians who want people to have the right to vote – not just nominally.”

The other diaspora

Despite the good intentions, Mr Lang has accepted that any aid will fall short of evening out the playing field for voters in the UK – particularly in comparison to the ethnic Hungarians in the east.

These non-domiciled Hungarians have been unflinchingly loyal to Mr Orban. And why wouldn’t they be?

In 2004, the strongman campaigned to provide dual citizenship to this population, while the left-wing vociferously opposed the proposal. The 2004 referendum failed, and the left won the battle – but they would soon lose the war.

Between two and four million ethnic Hungarians live in regions that belonged to Hungary before the much-maligned 1920 Treaty of Trianon.

Six years later, Fidesz took the 2010 parliamentary elections with a sweeping two-thirds majority, with Mr Orban at the helm.

By 2011, the administration granted dual citizenship – and voting rights – to ethnic Hungarians across the borders. Unlike those with a registered address in Hungary, they cannot vote for individual constituency candidates, but they are eligible to vote for national party lists.

When elections rolled around again in 2014, Fidesz were quick to remind these new voters of the left’s rejection a decade ago. Over 95 per cent of the votes cast by this group went to Fidesz.

This pro-government group can vote easily with mail-in ballots. By contrast, Hungarian migrants and emigres in the west – who vote overwhelmingly for the opposition – can only vote in-person at designated locations.

“Votes from abroad could make a difference for the first time”

Because experts predict the elections to be significantly closer than recent ones, marginalised supporters from abroad could be key for the united opposition – an unholy alliance of six parties, ranging from the far-right Jobbik to the left-wing DK – led by conservative Peter Marki-Zay.

Adam Sanyo, a data analyst who has modelled the upcoming vote based on the past three elections at the local, national and European levels, predicted 117 seats for Fidesz and 81 for the opposition.

“This is a slightly optimistic scenario, but we have about 25 to 30 really close constituencies with a very small margin of error – plus or minus four per cent of the given constituency,” he explained.

Which means issues like partisan gerrymandering could impact the outcome. With the electoral boundaries drawn in 2011, the opposition needs 300,000 more votes than Fidesz to win just 50 per cent of the seats in Parliament – this is 3.6 per cent of the total votes.

And now, mail-in ballots from the ethnic Hungarian diaspora could have a bigger effect on the final outcome as well.

“Fidesz is expected to get around 300,000 votes by mail, which is expected to give them two additional seats on the party lists – that’s their built-in advantage in the system,” said Mr Sanyo.

“But the opposition will also get some votes from those who live in the west, like London, who have two votes – the party lists and the constituency in which they have an address.”

While the mail-in group has been shrinking due to aging and assimilation, Hungarian communities in the west have been growing rapidly since the 2000s – according to Statista, every sixth Hungarian baby is born outside of the country.

Hungarian thinktank 21 Kutatokozpont estimates around 415,000 Hungarians living abroad in western countries – a significant increase from the 300,000 in 2018, when only 52,000 went to vote. This year, analysts expect around 80,000 to turn out.

Of the Hungarians abroad, more than 230,000 have said in a survey that they would vote if online voting was an option. Based on past elections, this could translate into 74,000 additional opposition votes – which would swing nine to fourteen constituencies for the opposition in a close election.

More than 184,000 respondents said they would turn out if voting required less than one hour of travel, which would translate into 50,000 additional opposition votes according to the thinktank’s model. In the event of a close race, these votes could swing three to six constituencies.

These numbers, according to Mr Sanyo, would impact the makeup of Parliament.

“It would make life so much easier for us”

Due to the high stakes, Tamas Csillag has been campaigning for better voter access in the west as the parliamentary representative for UK-based Hungarians who still have citizenship and a right to vote.

“They did not have representation in the Hungarian parliament – no representation of their interests in the Hungarian national legislation – so we decided to have someone from our party represent them,” he explained.

In the last year, he campaigned face-to-face across cities in the west with large Hungarian voter bases.

“We can’t get into television or radio, but we have people on the ground,” he said.

“Fidesz governs from state media – it’s really difficult to meet a Fidesz politician, and they don’t come out to meet voters,” said Mr Csillag.

A few weeks ago, Mr Csillag accompanied Marki-Zay on a campaign trip to London in hopes of engaging more UK-based Hungarian voters.

“The numbers are pretty good – I was hoping for slightly more, but we’re at least 25 per cent above the highest turnout previously,” said Mr Csillag, who is hoping around 70,000 will register by the deadline.

“In 2018, we found that 93 per cent of those in London voted for the opposition – seven per cent voted for Fidesz-KDMP.

“So, if it was up to us, Fidesz wouldn’t have even reached the threshold – they wouldn’t be in Parliament.”

Currently, he is campaigning to make mail-in ballots available to anyone living outside Hungary, including domiciled Hungarians abroad.

“Some Hungarians have to travel for several hours and queue for several more before voting, which isn’t easy to do – especially if you have kids or health issues,” said Mr Csillag.

“We tried to petition the government to open new voting stations, and they said it’s not an option – but we looked into the laws, and it’s allowed.

“More stations would be a temporary solution – an end solution would be getting the mail-in ballots, which would make life so much easier for us.”

When two plus two is five

Many of the voters in the UK are also concerned about whether their votes will be transported and counted correctly.

Over 20 civil associations asked the Organisation of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and its Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) to deploy a full-scale observation mission before the election – in place of the limited mission usually sent to EU members.

The call for closer supervision came after several anomalies were discovered during the 2018 national elections, when voters were bussed in from neighboring countries while others were allegedly intimidated or bribed.

To ensure a standard of fairness, Mr Sanyo has been training vote counters.

“The good thing is that the opposition has managed to recruit counters to almost all of the constituencies, so there will be very few places with no oversight from the opposition,” he said.

“I think there’s going to be attempts to commit fraud, but there will be much more oversight from people trying to prevent it, and it’s more likely to get reported this time than in 2018.”

But while oversight has improved for domestic votes, the mail-in ballots continue to lack any real transparency.

“There are no safeguards at all for the mail-in ballots,” said Mr Sanyo.

In 2018, Serbian press reported that Fidesz affiliates opened mail-in ballots and destroyed those cast against them. Fidesz won 96 per cent of these votes.

“It’s a horrible system – I know why it was put in place, I know how Fidesz expected a lot of extra votes from it, but it’s ridiculous that there are no safeguards,” said Mr Sanyo.

“We know, for instance, that there are 10,000 dead foreign voters registered to vote.”

An investigation by independent MP Akos Hadhazy also found that more than 3,000 people on the register were over 106 years old. Hungary’s average life expectancy is 76 years.

And concern only grew after discarded bags of burnt ballots were found in Transylvania last week. They were all for the opposition.

“There is no oversight, and there is no way of knowing the people who are voting should be voting,” said Mr Sanyo.

Mr Csillag’s constituents have echoed these fears.

“The vote will be closely monitored by both sides this time, so I keep telling people that it’s okay to vote here, but a lot of people have told me they don’t trust the system,” said Mr Csillag.

Which is no surprise – in 2018, many of these absentee ballots went missing sometime during their transportation to Hungary.

“I know a lot of people are afraid – my own mother wanted to like an opposition Facebook page, but then she got scared that her boss would see it and she’d lose her job.

“But I keep telling people to not be afraid – in the booth, you are alone.”