Three supermassive black holes which orbit close together could support Albert Einstein’s theory of ‘ripples in space time’, according to the University of Manchester.

An international team, including Manchester, Cape Town and Oxford scientists, examined six systems thought to contain two supermassive black holes.

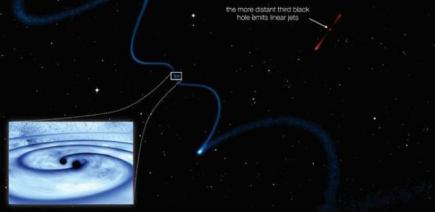

Their research found the rare trio of black holes more than four billion light years away.

The discovery could support Einstein’s general relativity theory, to transport energy as gravitational radiation.

OUT OF THIS WORLD: Discovery could be the first of many

The team used a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) to discover the inner two black holes of the triple system, which is leading the way in space research.

Dr Keith Grainge, from Manchester University said: “This exciting discovery perfectly illustrates the power of the VLBI technique, whose exquisite sharpness of view allows us to see deep into the hearts of distant galaxies.

“The next generation radio observatory, the SKA, is being designed with VLBI capabilities very much in mind.

“The finding suggests that closely packed supermassive black holes are more common than previously thought.

“These black holes orbit one another at 300 times the speed of sound on Earth.”

The technology used combines signals from large radio antennas separated by up to 10,000 km to see detail 50x finer than with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Future radio telescopes such as the SKA can measure gravitational waves from black hole systems as their orbits decrease.

At this point, little is known about black hole systems, which are so close to each other they emit detectable gravitational waves.

“This discovery predicts that radio telescopes such as Meer KAT will directly assist in detecting and understanding the gravitational wave signal,” said Professor Matt Jarvis from the University of Oxford.

“Further in the future the SKA will allow us to study systems in exquisite detail, and gain a better understanding of how black holes shape galaxies over the history of the universe.”

Although black holes may be so close together that telescopes cannot tell them apart, their twisted jets may provide easy-to-find pointers in the future.

The AMI telescope at Cambridge shows emission from this black hole system that increases at high frequency, directly due to extremely compact jets.

This may provide future telescopes a way to find binary black holes with greater efficiency.

Main image via ESO/WFI, with thanks

Article image via Roger Deane, with thanks

Inset image via NASA Goddard, with thanks