Three new entries and a leap from sixth to third place – the most-spoken languages in Manchester underwent a considerable reshuffle between 2011 and 2021.

The 2011 census was the first to ask respondents what they considered their main language, and the 2021 census followed suit.

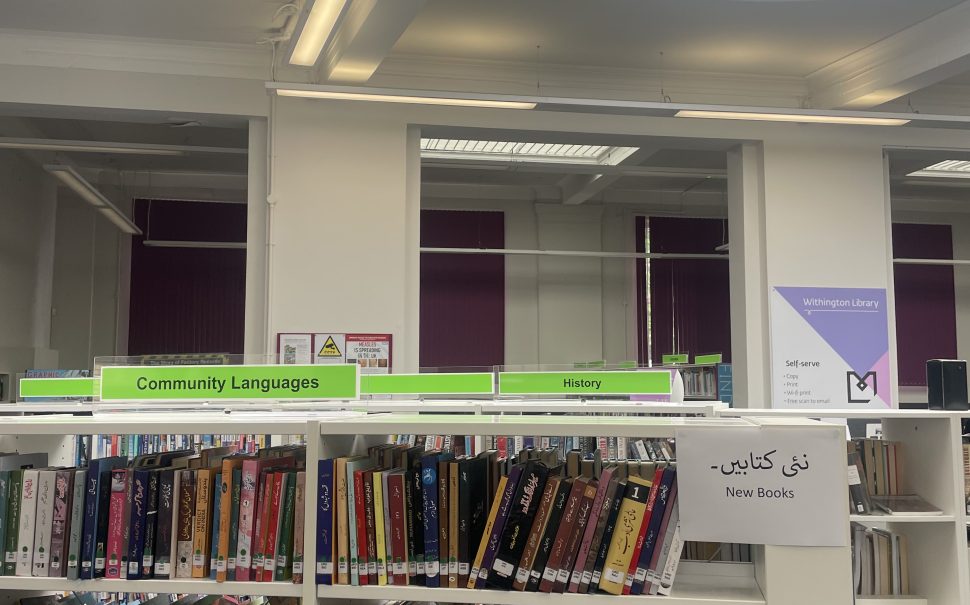

Besides English, the most spoken language in the region remains unchanged: there were more than 45,000 Urdu speakers across the region in 2021, a rise of over 40%. It is the most spoken second language in seven of the 10 boroughs, with the highest concentration in the Manchester ward at more than 17,000 speakers.

Adeel Khan, from Stretford, says English is his main language but he grew up speaking Urdu to his family. Now 35, he wants his children to learn it.

“My mum speaks English with my kids because that’s how they communicate. But I tell them to speak Urdu with my mum, so they can practise. So it can be hard finding that middle ground,” he said.

He thinks any issues with comprehension today will mostly be limited to the elderly, especially women. “When the elders came to this country, the men would go out and work, so would get a lot of exposure to English people.”

“Whereas the majority of women – not anymore, but in the 60s and 70s – would stay at home. If they did mingle, it would be with people within their community. So they had no reason to learn.”

Khan himself has never had to translate for a relative, but says it does happen: “Whenever my grandma has doctor’s appointments, she takes her daughter who almost acts as an interpreter to translate what’s being said. I can imagine that being common among older people.”

Khan is even-handed about the local services available in other languages. His children’s school has recently made its parent portal available in four languages. His local GP has multilingual posters too, and doctor’s letters come with a note advertising a translation service for those who need help.

He thinks the council is doing enough to manage the language barrier. “There’s got to be a point where you can’t put everything in another language. It works both ways, you should also be learning to read and write English yourself, though I know it’s not always the case [that you can]. But I don’t expect the council to translate everything.

“I think it just takes time. 20 years ago, all the imams would give their sermons in Urdu or Arabic. Now, at lots of the newer mosques, the imams are born and bred in the UK, and speak in English.

“My mum, when she came here, she couldn’t really speak English but now she’s got her own business. She’s still got that slight accent but other than that her English is good.”

Rochdale, Tameside and Oldham had the highest incidences of South Asian languages across the region. Despite being in the top five in eight of the 10 boroughs, the overall numbers of Punjabi speakers saw a fall of 4%. Bengali remains the most spoken second language in Oldham, but numbers are down by almost 20% across the region, and Gujarati speakers saw a fall of over 25%.

The second most spoken language across the region also remained stable: there were almost 25,000 Polish speakers reported in 2021, a rise of 17% on 2011. It is the most common second language in Salford and Wigan.

Maria*, 51, has been working as an EAL specialist and teaching assistant at a Catholic school in Wythenshawe since 2011. She considers Polish her first language but speaks several others which she uses at work to help parents and children who need it, recently using Russian with children from Afghanistan and Ukraine.

She also liaises with multilingual families, finding out which language is spoken at home, and who can speak English. Besides Polish, Hindi, Malayalam, Farsi and Urdu are common. “I don’t come across Polish people who don’t speak English well enough anymore. Maybe the new generation are learning it more diligently at school”, she said.

She has seen a lot of parents struggle. “But they have no one to talk to about that, because first of all, they can’t express themselves. As long as they can say their name and date of birth, many people decide very quickly that they can speak English. Therefore, they don’t need an interpreter.

“As long as they nod along, the assumption is that they understand, when they’re looking at your face and your lips are moving. But they don’t really. People won’t admit to it, but they turn around and they have no idea what you just said.”

How do teachers deal with this? “I would say that they don’t struggle with it, because they just continue speaking and they don’t care. They don’t have time to care.”

People struggling often go to their community for help, she says, to relatives or friends who know English. She saw free ESOL courses for people on benefits and leaflets at GP surgeries and libraries – but she could understand them as she already knew English. “I have been lucky enough to be learning it for a long time. I work in a public place and learn new words every day. I polish my language”, she said.

“For many people it’s not the case, and they are very limited. Many people just stick to the Polish church, listen to Polish TV, go to Polish shops, and make Polish friends. It is difficult to merge into society that way.”

Previously she worked as an agency interpreter. She has a dim view of the business: “The people working there are not trained interpreters at all. They claimed to require qualifications, but really they were so desperate they would hire anyone. We were paid peanuts.”

Most of her work was attending medical appointments. She attended a Caesarean section, an abortion – “I had to wait with the client before and after” – three prison visits and several probation meetings. “The feedback I got was usually very good, but occasionally someone said that I didn’t have a good knowledge of medical terms. But I had no idea what sort of appointment I was going to. We just get a job sheet, put the postcode in the car and go,” she said.

When she arrived in the UK, her daughter did not know any English. “As a foreigner with a child who was only 4, I was deeply shocked that there was nothing in place to help her. They just assumed that she will learn because she has to, because everyone speaks English sooner or later.” But when I ask her if the council is doing enough to help people learn, she is ambivalent.

“It’s difficult to say who should do that. Why would England have to do that? For the people who made a decision to come and live here? We came because we knew the language, though the English that I heard in Manchester was shockingly different to what I was taught.

“But British people were very nice. I find them very warm, welcoming and kind. They didn’t understand much about our culture, but it takes a few years and a lot of goodwill to learn about each other. That’s the point of living in a neighbourhood. Both sides are learning.”

Arabic has now passed Punjabi and Bengali to reach third place in the region with a total of 19,323 speakers, a rise of 78% on the 10,846 reported in 2011.

It was in the top five of seven of the 10 boroughs, finding its highest concentration in the Manchester ward, with 10,425 reported speakers.

At Dahlia House Cafe in Burnage, in a Southway Housing building, most of the volunteers in the kitchen speak Arabic.

Najwa Benramadin was already running a successful catering business when she was asked by the housing trust to run the cafe. From Libya originally, she speaks fluent English as well as Arabic and Maltese.

Rather than hiring catering staff, she decided to open voluntary applications to women from ethnic minority backgrounds.

“They all try the ESOL courses, but unless you’re advanced in education, they don’t really work. Coming from those backgrounds, there’s a big struggle, a big gap into employment, and the main reason being is the English language,” she said.

“I know they’re all amazing cooks but if we give them a chance to communicate with the customers, then it will push them more to practise their English. I’ve found that the best way to learn a language is by practising it, not sitting at a desk.”

The building itself is known as an extra-care scheme, where Najwa estimates around 90% of the residents are elderly native English speakers. “We have a lot of people that support what we’re doing, that encourage the girls to come in. We have both sides too, the downsides of being from different cultures and not being accepted. But we’re breaking barriers.”

The project has been a resounding success. Initially planned as a pop-up two days a week, the cafe is now open Tuesday to Saturday and enjoys a raft of regulars, each of whom Najwa greets by name as they stroll inside. And its impact has spread well beyond Burnage Lane: Sofra was lauded as Social Economy Champion at the Spirit of Manchester Awards last year.

It has managed to employ five out of the seven volunteers they had initially; the other two have secured jobs elsewhere. Among Najwa’s papers is a stack of over 20 applications from women all over Manchester for further positions.

Beyond the cafe, she plays a vital role as a kind of advocate for her community. “Southway had a community event where they wanted people’s views and they asked me if I could bring some people in. The room that they had wasn’t big enough for the number that I brought. It just shows that because I communicated it in a different language, it reached people.”

She thinks it is largely women from the community that struggle with learning: “It’s a culture thing…the lifestyle is different. They’re not outgoing, they’re not going to public or community events, whereas men will get more involved. It’s a confidence thing too: if you’re not sure what’s happening around you [due to a language barrier], you feel uncomfortable being there. Here, they know I speak Arabic, so they feel OK. I do feel there’s a lack of services that translate what’s going on.”

She gives the example of food hygiene training, which is compulsory for anyone working in a kitchen.

“For food safety, the training has only been produced in English. So none of my staff could do this qualification unless I interpret it for them, which I have done, which is why it’s become successful.

“When they can’t gain that qualification, that means they can’t get a job in the kitchen. But it’s all a big circle. It starts with volunteering, gaining the experience, the language, food hygiene, safety, then CVs and job search. And in the long run, maybe a big job, independence and empowerment.”

The decade also saw three new European languages enter the top 10.

It was Romanian that saw the biggest jump across the decade, going from 1,311 in 2011 to 10,261 in 2021, a staggering 682% rise which took it from 30th to 7th place. Romania joined the EU in 2007, but restrictions on how Romanians could work in the UK were not fully lifted until the end of 2013.

There were also 10,624 reported residents speaking Portuguese as their main language, a rise of 172% on the 3,620 speakers registered in 2011.

Spanish was the third language to enter the top 10, rising from 3,252 speakers in 2011 to 8,852 a decade later, a leap from 14th to the eighth most common language in the region.

Persian, French and Somali all exited the top 10, which was rounded out by Gujarati and Chinese (other) in the ninth and tenth spots.

Wigan and Salford had the highest incidences of European languages across the 10 boroughs, occupying 4 of the top 5 places in each respectively.

AllFM might be what the future of a truly diverse community offering for Manchester looks like. The radio station based in Levenshulme has a team of over 100 volunteers producing and presenting a schedule that is astounding in its diversity.

It doesn’t just speak to a wide variety of people (an Irish community programme, a pan-African show, LGBTQ+ hour) but does so in their own language, with an array of shows in Farsi, Ukrainian, Spanish, Urdu, Punjabi, Polish, Mandarin and Cantonese.

Station director Ed Connole is clear about their mission: “The aim of the station is essentially to be a voice to and for the various communities of Manchester. We are here to engage with as many as we possibly can, so in a way it’s natural that we would have numerous shows in different languages.”

An offering like theirs is rare. Does he feel they are filling a gap in the market? “Over lockdown we were putting out medical advice in different languages at the request of various agencies, in order to engage the more isolated communities whose English maybe isn’t great. I do think we came into our own then because we could reach out to various demographics and get messages to them.

“These presenters are not living in ivory towers. They’re living and working in the same areas as the listeners. I think that builds up the trust and the relationship between audience and presenter. They are no different from the people they broadcast to. They are those people.”

The majority of presenters are the legacy of previous training programmes the station has run. Participants complete their training by hosting a show live on air, and then get the chance to pitch their own: the successful ones are taken on. “We train people in a skill and then we put their skill to use”, as Connole puts it.

He says the council, who provide some core funding, has always been supportive: “I think they recognise the strength of community radio”. Public reaction has been warm too: “It’s very positive that we have people who can speak for and to their communities, who in turn engage and embrace the shows.”

He can’t say what might be coming next: “We don’t tell people what shows to do. The community brings the shows to us, then we help them develop it.”

“Our ethos is quite simple – by the community, for the community. We remember that when we’re developing shows, training and schedules – we are merely a catalyst providing a voice for the various communities of Manchester.”

*Name changed at interviewee’s request

Image Credit: Mancunian Matters