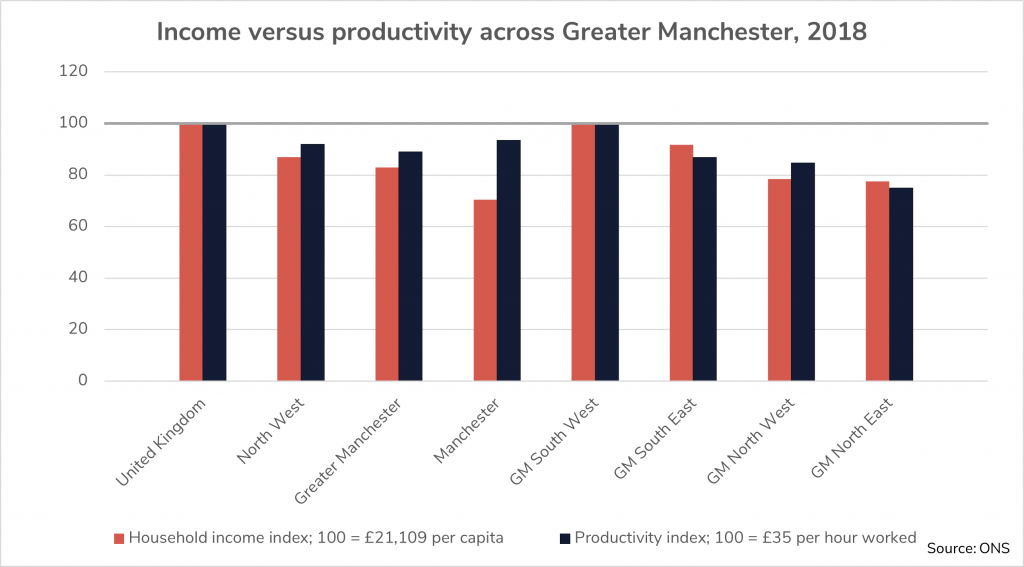

Every Greater Manchester region bar one was below the national average for both household income and productivity in 2018, according to an Office for National Statistics report which writes of a clear north-south divide.

Analysing the most recent available figures for income and productivity, the ONS found Greater Manchester had an average gross disposable household income per capita of £17,511 – 84% of the national average of £21,109.

As for productivity, Greater Manchester’s gross value added was £31.20 per hour – 89.1% of the £35 average.

Both household income and productivity are positive indicators of an area’s economic success – but the difference between the two figures can be considerable.

In the Manchester region, for instance, the household income figure (GDHI) was only 70.4% of the national average – among the country’s lowest. Productivity, on the other hand, was comparatively high, at 93.5%.

The ONS report suggests that one reason for such disparity is a “commuter effect” – high-income earners contributing to Manchester’s productivity may live outside the area.

In Greater Manchester, only the South West region, which includes Salford and Trafford, scored above the national average in either category, with its average household income 0.4% above average; productivity, however, was 0.4% below.

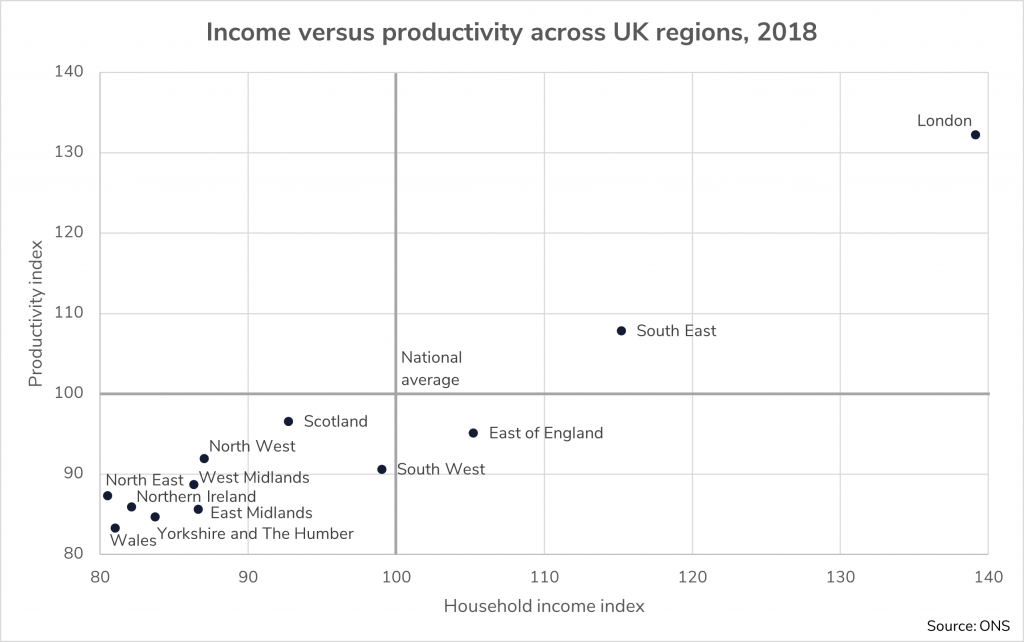

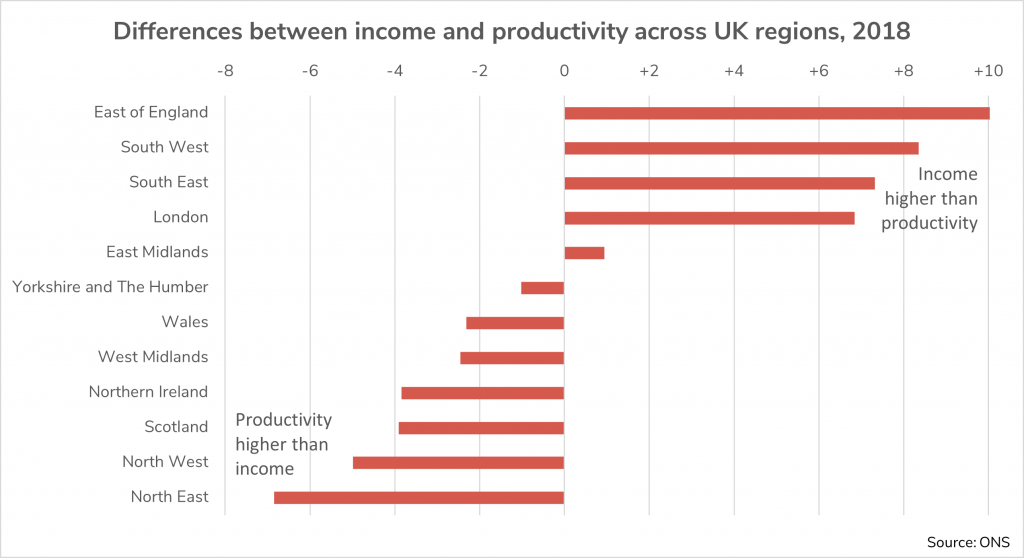

The statistics also reveal the disparities between income and productivity across the country’s regions – revealing what the report calls “a clear north-south divide at a regional level.”

In the south of the country and the East of England region, the income index is substantially higher than the productivity index – but in other regions, and most of all the North West and North East, productivity is higher than income.

In other words: in northern regions, high levels of value added through work – higher productivity – do not translate into higher income.

Charlie McCurdy, an economist with the Resolution Foundation, put the ONS analysis into a broader perspective: “When you hear talk about levelling up and sorting out these massive regional divides – that’s focusing at the regional level.

“If you use something like a metro area, then actually, the regional divides look much more in the middle of the park, more similar to France and Germany.”

Further, Mr McCurdy argued, the productivity and income statistics paint different pictures: “Productivity gaps have been growing in the UK for the last 20 or 30 years. But if you look at household income, those gaps have actually been shrinking between regions.

“There are a few reasons why that’s happened, including success stories like the minimum wage, and employment rising in traditionally low-employment areas.”

In terms of both productivity and another measure – GDP per worker – Mr McCurdy added that the UK’s larger cities outside London tended to underperform economically.

He said: “London and other parts of the South East tend to perform much better on things like GDP per person or productivity, but there’s a second tier of cities, including Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham, punching well below their weight when you compare their relative performance to other countries.

“These big spatial differences are explained by the sorting of people in terms of education and skills. You’ve got the most highly educated people in the capital city, and relatively few in the rest of the country.”

The Resolution Foundation’s own report (made jointly with the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance), The UK’s decisive decade, was published on 18 May – the day after the ONS’s analysis – and launches the think tank’s Economy 2030 Inquiry, which examines how the UK can achieve economic success over the next decade.

The ONS’s full report can be found here.

Main photo: Manchester Town Hall. Image by Parrot of Doom via Wikimedia Commons