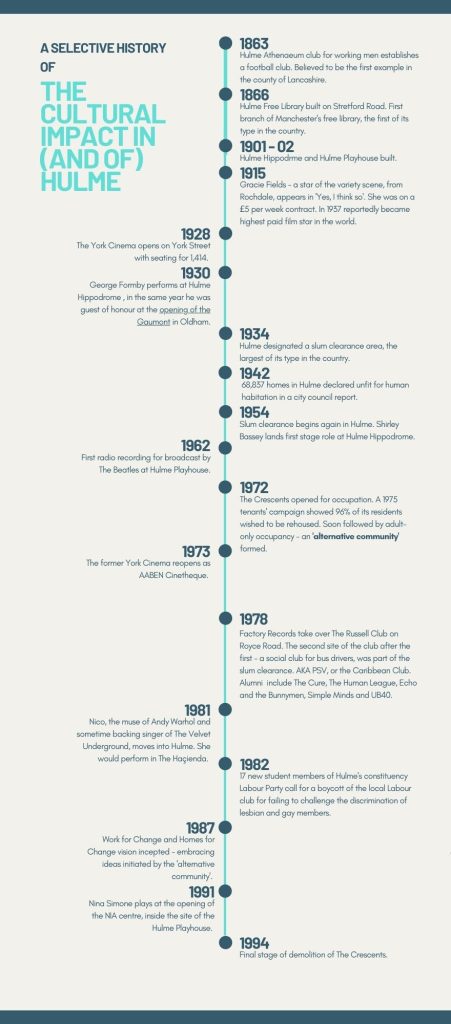

In the year that the 5,000-seat entertainment venue The Factory opens in Manchester at a cost of £186m, KEVIN GLENTON went along to Hulme Hippodrome, where up to 3,000 people were once entertained by A-list stars such as George Formby, Laurel and Hardy and Gracie Fields. This now-decaying venue was at the heart of the community and a campaign group is fighting to preserve the building and provide another home for arts and culture.

“It’s always good to remember where you come from and celebrate it. To remember where you come from is part of where you’re going.”

So said Anthony Burgess – novelist, poet, screen-writer, broadcaster, composer, son of Manchester and the borders of Hulme.

His mother was a singer and dancer on the stage and his father played piano in the same music halls. Burgess remembered him providing a solo soundtrack to Fritz Lang’s seminal film Metropolis during a Saturday matinée in 1927 at the Palace Cinema, located on Princess Road in Moss Side.

That building would have shone as a beacon of escapism for the 10-year-old John Burgess Wilson, as he was known then, and hundreds of children like him. It was near the tobacconists which his father ran.

The venues glowed with colourful advertisements for upcoming star turns and shows – today, protruding foliage from Hulme Hippodrome’s brick façades are the only sign of life.

Prominent in working class areas where locals rapaciously consumed their guttural content, these fine Victorian and Edwardian structures had foundations and cornerstones as deep as the communities they served. Inside and out, their owners spared little expense to provide colour and furnish the imagination of those whose daily view of each other and the real world was through a dark cloud.

It’s a short walk to Hulme Hippodrome from where the Palace Cinema once stood. One of the remaining variety theatres in the North West and the symbolism of this particular journey provides renewal and hope to a company who have come together to save it from potential ruin.

Seven A4 sheets of paper, some adorned with the crest of Manchester City Council, are attached to one of the walls of this grade II listed building, to give notice of a Section 215 action. Signed and dated 14th February 2022, a two month notice period begins on 16th March.

A Section 215 (to the owner of a building) provides a local authority with the power (in certain circumstances) to take steps requiring land to be cleaned up when its condition adversely affects the amenity of the area.

Save Hulme Hippodrome are not the owner but are fighting to save this 121-year-old edifice with a vision of invigoration via help from the community it once served to entertain, to now collaborate and rebuild it. A crowd-funding campaign raised over £17,000 in less than a month to cover the cost of potential surveys and valuations.

Chairman and director Paul Baker said: “It’s almost the last man standing.

“This is such a magnificent space. It has got an amazing heritage.

“So many things occurred in this community, which actually had a massive cultural impact on Hulme, on Manchester.

“And still does to this day and what we’re hoping to do is to find a way to make that building relevant in the 21st century and to think about how that could be used as a flexible space which would include the amazing Rococo theatre space which would have to be protected.

“There’s shop fronts, there’s all sorts of things we can do.”

The 3,000 seat building was constructed in 1901 and built for William Henry Broadhead, founder of a circuit of 17 theatres in the North West, marking a huge contribution to working class entertainment.

Next door is the Hulme Playhouse, another in Broadhead’s stable. The designer of both was JJ Alley, responsible for several other theatres in Manchester, including the Metropole, the Royal Osborne and the Queens Park Hippodrome. Sadly, many of these are no more.

Hulme Hippodrome began life under the name of the Grand Junction Theatre and Floral Hall with an original plan to perform melodramas.

After four years it was renamed and began to shake with the laughter and raucousness in the brightest music hall traditions, now as a variety theatre.

Over the years it hosted Gracie Fields, George Formby, the Tiller Girls as well as classical pianists like Marie Novello. Shirley Bassey is said to have had her first stage job there. A post called ‘Tracing the history of Hulme Hippodrome’ by Sarah K Whitfield expands more on the significance of the performances by touring black artists.

The site was prominent and elegant along a main road where trams ran back and forth. It’s hard to imagine 3,000 people jostling in and out now as that road has been repositioned, the old trams have gone and the building stands amongst terraced housing. Baker says it’s hidden in plain sight.

Once television consumed variety and its offspring of radio variety (the BBC occupied the Hulme Playhouse next door for a number of years), the echoes of laughter gave way to snooker and bingo and so began the slow decline of the building.

The Theatres Trust, set up by a 1976 Act of Parliament, work to promote the better protection of theatres for the benefit of the nation. They describe how the main body of the theatre stood empty for nearly 20 years until the building was purchased by Gilbert Deya Ministries, an evangelical group. They operated from a tiny part of the foyer and the main area was unused.

Closure to a now dangerous building in 2017 saw squatters move in until they were removed in 2018. The building has been left vacant since then and a slide into disrepair seemed inevitable. The current owner entered the building into an auction in January 2021 but it was not sold.

In the early part of that year, members of the local community, Friends of the Hulme Hippodrome, Save Hulme Hippodrome and the Hulme Community Forum came together to form a collective whose stated aim is to regenerate the building for the people of Hulme and Manchester.

And the renewed vigour and hope began.

Linking the past to the future

Perhaps the hope that links this working-class suburb via the committees which make up the body of Hulme Hippodrome comes via a bridge.

To get to Hulme Hippodrome from Anthony Burgess’ old stomping-ground on foot, you cross the Epping Walk Bridge and pass through the university campus until a narrow path brings you out just opposite.

It’s hard to recognise the crossing these days, which spans Princess Parkway on its way into the city, from its place in the sparse images of realism taken by Kevin Cummins in 1979 of then burgeoning post-punk music group Joy Division.

The glass and steel developments in the photographer’s updated image, on the other side of the Mancunian Way, look like giant USB-sticks plugged into the other side of this ribbon of road which separates Hulme from the 21st century, insulting it as their towering windows reflect years of interference and experimental planning back onto the suburb.

In 1979 the band could have turned to face The Crescents, a failed housing scheme of four blocks which within two years of its construction in 1972 was deemed unsuitable for families. By 1984 the council stopped charging rent to tenants but carried on supplying electricity to those who needed it. An eclectic home for beatniks, punks and a sub-culture had been born and raised by this point.

You could walk further past the bridge, turn left onto Bonsall Street and then turn left again where it joins Old Bailey Street. You will have just passed the site of The Russell Club, where a group of anarchic pacemakers took over a quiet Friday night on 19 May 1978 for the inaugural event of Factory Records.

Factory founder Anthony H. Wilson (another whose father ran a tobacconists, this time in Salford) has a legacy living on through numerous projects in the city. His son Oliver is another director of Save Hulme Hippodrome. The impact that these events had on the creative souls of Manchester were first heard in Hulme.

Paul Baker said: “The Russell Club was here, the AABEN (an independent cinema which became a focus of community life, eventually showing arthouse films to stir the ‘alternative’ lifestyle of Hulme residents), all these cultural artefacts that used to play an important part in…you know, where does HOME come from?

“The Russell Club, that’s now turned into The Factory. These big, mega projects, they’re spending millions of pounds on, let’s see some of that money invested in Hulme, which actually was the genesis of this kind of energy.

“This community gave opportunity for those kind of things which have now obviously become establishment and let’s be the laboratory, let’s be the sort of space where we generate new ideas, new spaces, new possibilities and new sorts of ideas about what Manchester can be.”

We met at the company’s Spring Festival to celebrate the Hippodrome’s heritage, held at Hulme Community Garden Centre. Shadowed by the building they wish to save, this is another fine example of a community-led project, launched 20 years ago, a literal example of life being breathed back into the area. Their work inspires sustainability and educates schools, colleges and the local communities. Laced between the polytunnels and bedding are old flyers and playbills for the Hippodrome.

I met a man in his eighties, brought along by his daughters. I spoke to him for five minutes. He told me how he and his friend used to put a shirt and tie on each Saturday evening and spent a night at the Hippodrome. His eyes softened and his face was smiling at the memory. His daughter told me that he had not been back to the area for years.

Paul Baker agreed to meet a few days after, in the headquarters of NIAMOS, listed as a radical arts and culture centre and situated in the Playhouse Theatre, next door to the Hulme Hippodrome.

In the five minutes before he arrived, young children were rehearsing on stage and a piano was being played in the background. People were busying the area for a celebration of Nowruz and the start of the Afghan new year.

Baker gave a quick tour around this smaller neighbour of the Hulme Hippodrome, built at the same time and in the same style to give me a sense of proportion and the task ahead for anyone looking to renovate.

Baker said: “Like a phoenix it rises again. And I think that’s what we’re saying, you know about both this building, in some way, metaphorically and symbolically representing that kind of amazing resilience and people do try to keep the spirt.

“The people feel they know what Hulme is…they will tell you what Hulme is and what it represents.”

Baker celebrates all that the area has offered and will continue to offer against the backdrop of the gentrification occurring over the other side of the A57 in Cummins’ shots.

He said: “Hulme needs to as much celebrate its distinct culture and we have to be the counter to the Northern Quarter, so in a sense it’s about bringing together what makes Hulme Hulme, historically and what it is today.

“The very fact that downstairs you’ve got this Afghani (celebration). Hulme and Moss Side in particular, you know, Somalian, Ethiopian, going back, you can roll it back, African, Jamaican.

“You know, there’s all sorts of communities here, Irish, Ukrainian, you name it. And I think it’s always been, because it’s closer to the docks, it’s always had that.

“When I see the ‘top ten things that Manchester was involved’ in, people tend to forget the Pan-African congress met here. I think we need to celebrate its diversity.

“This is a community that suffered trauma, not once, not twice, but three times. It was bombed, when the back-to-backs went, then they knocked down and built The Crescents and they knocked The Crescents down.

“We’ve got two wonderful older women who are sisters, who remember the Hulme (Hippodrome) and the thing that was most memorable for them was a woman who did a feather dance, they’ve never forgotten that.

“But they said that they came back, one of them went to Germany with her husband and she came back, shortly after the war in the early fifties probably and literally, her street wasn’t there anymore.

“When she got on the bus she asked to buy a ticket, the guy said ‘Are you sure?’. She got off and there was nothing, nothing. Just a street corner.”

My final meeting with Paul Baker in early May is in the company of Tony Baldwinson and Mike Bath, fellow committee members. They were holding a meeting at Kim’s Kitchen, known to anybody who passes through this part of Hulme.

The walls there are embellished with poetry, sketches and interpretations of life here – the Epping Walk Bridge features upstairs – and the tables, chairs and stools indoors and out invite collaboration and collectivity.

We were also shown around a shared workspace above Kim’s, part of a co-operatively managed workspace provided by Work for Change. A further embodiment of the vibrancy and diversity in the area, spaces are managed by the tenants, who set the rents and budgets. Their directory includes an artist studio, a company providing opportunities for adults with learning disabilities in the arts, charities and support groups. What more could they do in a larger community space?

The Save Hulme Hippodrome group were listening to a passionate newcomer who came along with publicly available building plans from Hulme Hippodrome’s past and offered his insight into three possible other histories the building has had. At once, the members of the committee turned into planners, architects, shop-keepers and engineers.

His words seem to inspire them into adding more to their vision and dreams for Hulme.

“We can destroy what we have written, but we cannot unwrite it” – Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange.