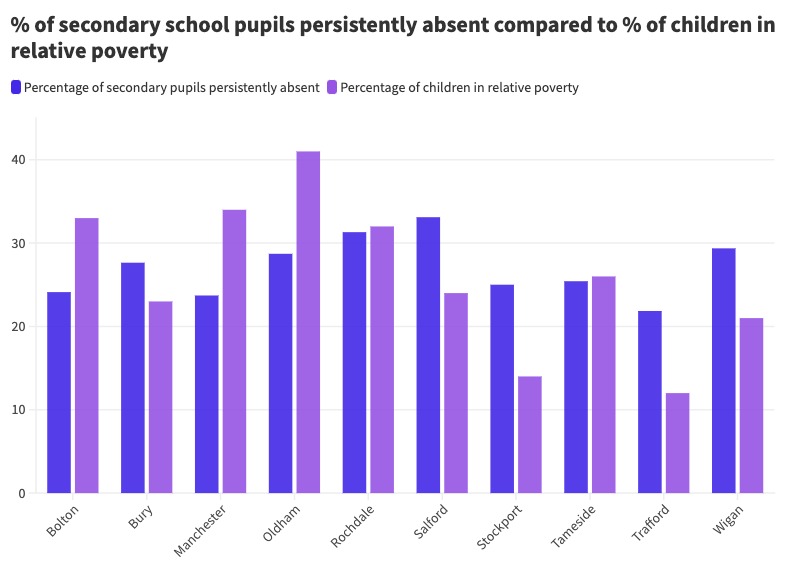

A parliamentary report claims there is a strong link between low school attendance and low income – but analysis of attendance data in Greater Manchester’s ten boroughs suggests the city-region bucks this trend.

A House of Commons Education Committee report published at the end of September 2023 said “a major driver of low attendance is low income” across the UK.

But this link is not clear in Greater Manchester, when the latest child poverty statistics are compared with the latest figures on school absenteeism.

What caused the spike in school absenteeism rates?

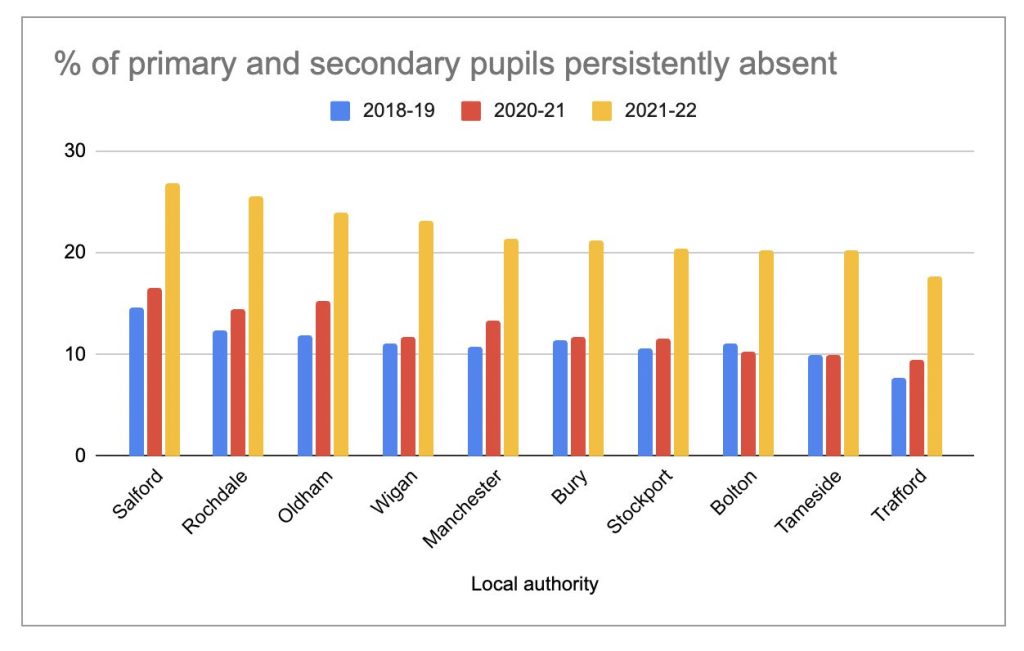

There was a huge increase in persistent absenteeism between the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. Data was not collected for the 2019-20 school year, due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic coincided with the spike in absenteeism rates, and indeed goes a long way to explaining the increase.

Elizabeth Adamson, a school social worker based in Tameside, agreed with this explanation.

She told Mancunian Matters: “I do think that Covid made people much more conscious of illness. Before it was the norm to send them in unless their heads were falling off.

“The way it was suddenly OK to have your child out of school for long periods [during the pandemic] has potentially made people wonder how necessary it is for them to be in every single day, come hell or high water.”

The Education Committee also found that since the pandemic, “parental attitudes to illness and attendance have shifted”.

Nick Gibb MP, Minister of State for Schools, told the committee that “there is higher caution among parents about sending their child into school if they are showing symptoms of a cold or something”.

The Association of School and College Leaders instead pointed to ‘changing advice to parents from government about how to handle illness in children’ as helping explain increased absenteeism.

This ‘cultural’ explanation fits with the statistics for Greater Manchester. In Trafford and Stockport nearly twice as many children are persistently absent than are relatively poor. The of obstacles living in poverty brings cannot explain that.

Since 2016, the national rate of persistent absenteeism — missing at least 10% of lessons — has doubled from 10.1% to 20.5% in 2021-22.

In some areas of Greater Manchester the increase has been even more severe. Over the same period, the proportion of pupils persistently absent in Wigan and Trafford more than doubled, from 10.6% of pupils to 23.1% in Wigan and 7.5% to 17.6% in Trafford.

Yet Trafford has by far the lowest rate of relative child poverty in Greater Manchester, at 12%, with Stockport not much worse at 14%, where persistent absenteeism rose from 10.5% to 20.4%.

Relative poverty is defined as an income of less than 60% of the median – or middle – wage that year.

Across the UK, 20% of children up to age 15 meet this criteria.

By this measure all of Greater Manchester’s boroughs, apart from Trafford and Stockport, fare worse than the national average.

In Salford and Tameside around one in four children lives in relative poverty, whilst in Rochdale, Bolton and Manchester that figure is around one in three.

Across Greater Manchester, Salford saw the most persistent absenteeism, with more than one in four pupils missing more than 10% of lessons. Yet for child poverty, Salford ranks in the middle of Greater Manchester’s boroughs.

Rochdale was second for absenteeism, also with one in four pupils persistently absent. The borough has the fourth-largest proportion of children in relative poverty.

Oldham, the borough worst affected by child poverty, meanwhile saw the third smallest increase in persistent absenteeism.

The link between child poverty and school attendance therefore seems weak in Greater Manchester.

In many of Greater Manchester’s boroughs, far more children are poor than are persistently absent. In Oldham, Manchester and Bolton particularly, children in relative poverty are attending school regularly.

In the constituencies of Bolton South East and Oldham West and Royton, 44% of children live in relative poverty — the sixth worst performing areas in the country.

Yet across Bolton, only 20% of pupils are persistently absent, and around 25% of Oldham’s pupils.

For Greater Manchester, then, the Education Committee’s findings on the links between child poverty and school attendance do not wholly convince.

Seamus Murphy, CEO of Turner Schools Trust, told BBC Radio Four: “Children who are in families who are experiencing deep poverty are more likely to struggle to get to school, for all sorts of various obvious reasons.”

As hard as tackling child poverty is, educators in Greater Manchester will also have to look at other factors to improve school attendance.