Antisemitism is currently at the forefront of many people’s minds.

CNN’s study into antisemitism in Europe last November revealed that a fifth of British people think that more than 20% of the world is Jewish, and a quarter of Europeans think that Jewish people have too much influence in business and finance.

Back in January, a report by the Independent revealed that 5% of UK adults were Holocaust deniers, with a further 8% believing the scale of the genocide was exaggerated.

Then last month, the Equalities and Human Rights Division launched a formal probe into antisemitism in the Labour Party, following many years of speculation about just how entangled the party is with the issue.

It seems to have come as a shock to the general public – but just how well do we all know what casual day-to-day antisemitism looks like?

With this question in mind, MM decided to run a survey that tested participants on their knowledge of antisemitic stereotypes, and conspiracy theories.

The first category on the survey covered stereotypes about the Jewish people, with participants being asked to identify whether or not they had heard them before.

The most well-known of the 15 provided options was the idea that all Jewish people are greedy or rich, with 93% of respondents having heard this stereotype.

It is one of only three known by 50% or more of respondents.

Second most well-known, at 70%, is the idea that Jewish people control the government, media, economy, and/or world. In third, at 54%, is the idea that Jewish people are untrustworthy.

The most commonly known stereotypes paint a picture of the Jewish people as untrustworthy and power-mad, particularly in regards to money.

The basis for these stereotypes dates back to the Middle Ages – the Church at the time forbade Christians from lending money while charging interest.

Naturally, as they were not Christian, Jewish people were not held under this ban. With Christianity as the largest religion in Central Europe at the time, and Judaism as the next largest religion (making them both large enough to be recognisable, but small enough that they could be easily targeted), Jewish people became associated with ‘greedy practices’ – and this stereotype has lasted the ages ever since, simply thanks to an ancient Church-made rule.

Of the remaining 12 stereotypes, seven were recognised by 25% or less of respondents. It is interesting to note that the four stereotypes directly linked to Christianity are not equally well known, and that 64% of Christian respondents hadn’t heard any of them.

In all cases, less than 20% of respondents who know of said stereotypes hold Christian beliefs. In stark contrast, only 30% of Jewish respondents hadn’t heard of these specific stereotypes.

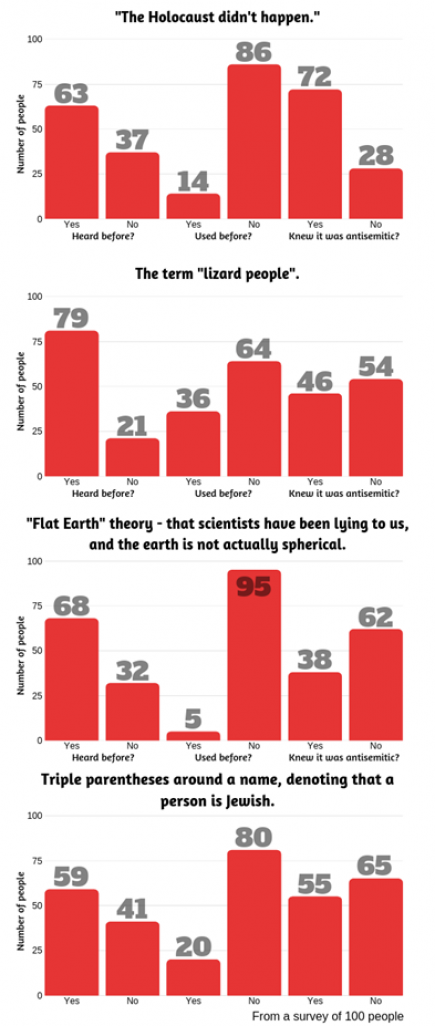

The second segment of our survey dug a little deeper – had respondents heard the following phrase or conspiracy theory, had they ever used it before, and were they aware that it was antisemitic (or if they were unaware of it, would they have been able to tell?)

Perhaps surprisingly, the most well-known option from this section was not the concept of Holocaust deniers (63%), but instead the idea of lizard people at 79% – a difference of 16%. “Lizard people” is also the most commonly used option, at 36% – which is perhaps unsurprising to regular users of the internet.

The term has become a popular way of referring to someone who’s socially awkward, with many people unaware of its initial antisemitic roots – this is represented in our results with 54% unaware that it was an antisemitic term.

“Lizard people” can easily be linked to the fabricated antisemitic text ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’.

The text details a supposed plot by Jewish people to control the world, and has been debunked several times over. Despite this there are still a great number of people who praise it – including former footballer and sports broadcaster, David Icke.

Icke is now a professional conspiracy theorist, whose most popular theory tells of an ‘inter-dimensional race of reptilian beings’, called Archons, who control the world.

There is a clear parallel between this theory and the aforementioned antisemitic text which he has endorsed, showing just one clear link between antisemitism and the concept of ‘lizard people’.

The next most well-known option, the Flat Earth conspiracy theory (which sits at 68%) finds its origins in a general belief by antisemites that the Jewish people that they believe control the world ‘spread misinformation’ – most conspiracy theories can actually be linked back to antisemitism, including anti-vaccination myths and denial of climate change.

The least well known of these options – triple parentheses, at 59% – is more recent, and originates on the internet. Called an ‘echo’, they were popularised by a white-supremacist, neo-fascist blog called The Right Stuff, and fascists use it as a flag by placing an echo around the names of Jewish people.

Following this, for our final section respondents were asked whether or not they thought a number of controversial celebrity incidents were antisemitic or not.

Of 13 scenarios, only one was agreed to be antisemitic by all participants – an incident involving the angry tirade of a well-known actor and filmmaker. While the remaining twelve proved controversial, with many instances of mixed opinions, only one was believed to be wholeheartedly antisemitic by less than 50% of participants.

So exactly how does the general ignorance of antisemitism impact people? MM had the opportunity to interview a Jewish person who has encountered antisemitism frequently – they wish to remain anonymous for fear of their safety, so will be referred to as P.

P has run a Tumblr blog for five years maximum, and uses it to post about their general interests – music, anime, but more and more frequently important current affairs issues. From the very start of that blog’s lifespan, P has received threatening messages.

“I would have to turn off the ask and submit inboxes in order avoid that. And then at some period of time, I was being… I wouldn’t say stalked, but I had been repeatedly watched and threatened by a specific user, who I’m suspecting sent me antisemitic threats.

“They’d send death threats, suicide threats, telling me to kill myself, saying I deserve to die. And then a lot of the time, the threats would turn antisemitic for no reason at all except for the fact that I was Jewish. There was a whole thing back then where people would send Jewish users uncensored gore through the submit box, just because they were Jewish.

“[At that time], I would’ve been about 16. But the first instances of hate messages, when I first got my blog, I would’ve been about 13 or 14.”

Naturally, receiving death threats for so long from such a young age was traumatic for P: “It’s had a great detrimental effect on my mental health, especially in regards to my paranoia.

“I have noticed antisemitism is becoming more and more common and normalised – and the way it correlates with the political climate is no coincidence or surprise. I think I experience it more online because, like other types of harassment, it’s easier to hide behind a screen. The online antisemitism I’ve experienced is usually more violent and brutal as a result.”

When asked how gentile people can assist in combating antisemitism, he gave this advice: “Gentiles should educate themselves on how to spot antisemitic statements and dogwhistles and step in to shut such instances down when possible.

“This goes for casual and overt antisemitism in daily conversations, and casual and overt antisemitism online, especially when disguised as jokes or memes.”

P also notes that the Anti-Defamation League does great work to combat antisemitism, and is an amazing resource for anyone hoping to start trying to make a difference.

PROPORTIONALITY: The Manchester Reform Synagogue is a clear example of just how small the Jewish population is, as the only synagogue in Manchester city centre

More locally available is the Community Security Trust (CST). MM had the chance to talk to the Director of Policy, Dave Rich on what antisemitism is like on a UK-based scale.

“We [the CST] support victims of antisemitic hate crimes and generally represent the Jewish community to police and government on matters relating to antisemitism, terrorism, security and extremism,” said Rich, on his organisation’s work.

He told me that the CST don’t just work to prevent antisemitism after the fact – they also aim to nip it in the bud too.

He said: “CST’s youth project Streetwise works with the Muslim organization Tell MAMA on a joint project called Stand Up! that uses Jewish and Muslim educators to run sessions in schools about antisemitism and Islamophobia.”

But just how often do they receive reports of incidents? Unfortunately, an awful lot.

In 2018, CST recorded a total of 1652 antisemitic incidents across the UK, with over 100 incidents in ever calendar month. This is a record high annual total, and it seems there’s a fear that the current political climate will only worsen this.

Rich said: “The problem of antisemitism in mainstream politics has definitely affected the overall prominence of antisemitism in wider society, and has had a strong impact on Jewish experiences of, and exposure to, antisemitism.

“Attitudes that used to be confined to extremes are now much more commonly heard in regular society, especially on social media.”

The Genocide Convention of 1948 was created in order to prevent events like the Holocaust ever happening again – yet in spite of this a great percentage of society fails to recognise basic antisemitic dogwhistles, with education on the Holocaust being minimal in the American system, and only taught in the UK if History is continued to GCSE level.

With so little compulsory education on the subject, and left-wing people expected to sit back in the face of discrimination as proof that they are ‘liberal’, maybe the resurgence of antisemitism shouldn’t come as such a shock after all.