Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham recently introduced the Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s (GMCA) plans for a ‘Manchester Baccalaureate’ – or MBacc – to the city-region’s schools.

He claimed it would create an “equal pathway” for pupils wishing to go into a technical career instead of applying for university.

But what do the new plans actually mean, how are they so different from the ‘English Baccalaureate’ currently in place across the country – and what does the Department for Education think?

Mancunian Matters has put together a full guide with everything you need to know about the new system, how it could be a game-changer for young people in the city, and why it has courted controversy at a national level.

First things first: what is it?

The MBacc is a new core set of GCSEs that lean more towards technical subjects than the current ‘English Baccalaureate’ (EBacc) system.

The idea is to allow 14- to 16-year-olds who already know they do not want to take the academic route to focus on skills-based subjects that will help them get jobs in the most needed industries in the city-region.

Councillor Eamonn O’Brien, now GMCA lead for Technical Education and Skills, said: “Employers say there is wide demand for skills in areas such as digital, education and early years or construction, but our current skills system is not linking young people to these jobs.

“Our ambition is to start with what is already working well, in this case the well-travelled route to university, and ensure young people have the same route to technical education.”

Under the new core set, English Language and Maths will still be compulsory, alongside ICT or Computer Science.

Then pupils will have a choice of subjects, from engineering and the sciences to creative subjects.

The Mayor is also considering other GCSEs such as Business, Economics, and PE, but these are yet to be confirmed.

How is it different from the current GCSE system?

Burnham’s MBacc is supposed to sit alongside the current EBacc system.

Under the EBacc, all 14-16 year olds are encouraged to sit a set of subjects that according to the Department for Education “keep young people’s options open for further study and future careers”.

These are English language and literature, maths, sciences, geography or history and a language.

The system was introduced by Michael Gove in 2010 primarily as a way of measuring the performance of schools – with the argument being that the more pupils sitting and passing these subjects, the better the school.

I’ve been hugely encouraged by the overwhelmingly positive response to our plans for technical education and the #MBacc.🙏🏻

— Andy Burnham (@AndyBurnhamGM) May 24, 2023

In case you missed it, here’s a brilliantly simple animation explaining it all.👇🏻pic.twitter.com/pAfafHmKu0

If there’s already an EBacc, why bother with this MBacc thing?

In 2021, the government set a new ambition for the scheme. They wanted to see over 90 percent of young people leaving school with EBacc qualifications by 2025.

Yet EBacc entries across the country have flatlined at around 40 percent since 2014.

In Manchester, the number of 16-year-olds leaving school with grades in EBacc subjects lies at 36 percent.

Burnham argued this is because these subjects are geared towards academic students.

He said: “For too long, we have ignored the value of technical skills and that ends today in Greater Manchester.

“The EBacc is great for young people who want to go on to university, but there is no equivalent suite of qualifications at 14 and 16 that align with the real-life employment opportunities being created in our city-region.”

The MBacc is supposed to provide a clearer path for those pupils, by allowing them to specialise in technical skills at a younger age.

Will it help school inequality?

There’s no way of knowing until the MBacc is trialled what impact it will have on pupils’ lives, but the current system has a couple of major issues that have been criticised by teachers, parents and the media since its introduction.

For one, government statistics from 2021/22 indicate that disadvantaged pupils – who have been eligible for free school meals in the last six years – were a third less likely to be entered for the EBacc.

This seems to indicate that under the current roll-out of the EBacc system, some of the most vulnerable pupils wind up slipping through the net and leaving secondary education without the qualifications they need.

Equally, the EBacc has been blamed for the decline of creative subjects, as schools are forced to make difficult budgeting decisions and prioritise spending on EBacc subjects.

Councillor O’Brien claimed that the MBacc was not only about offering an alternative route for pupils, but also “to create a system which ensures the city-region is a fair and equal place for everyone to get ahead in life and work”.

Is this all about schools?

No. Burnham emphasised the change will not just help young people into work. He also wants to address the growing skills gaps in key industries in the region. Some examples listed by the GMCA include:

- Manufacturing and Engineering

- Financial and Professional

- Digital and Technology

- Health and Social Care

- Creative, Culture and Sport

- Education and Early Years

- Construction and Green Economy

When does the change happen?

The MBacc is set to be introduced for Year 9s from 2024.

What does the future look like for an MBacc student?

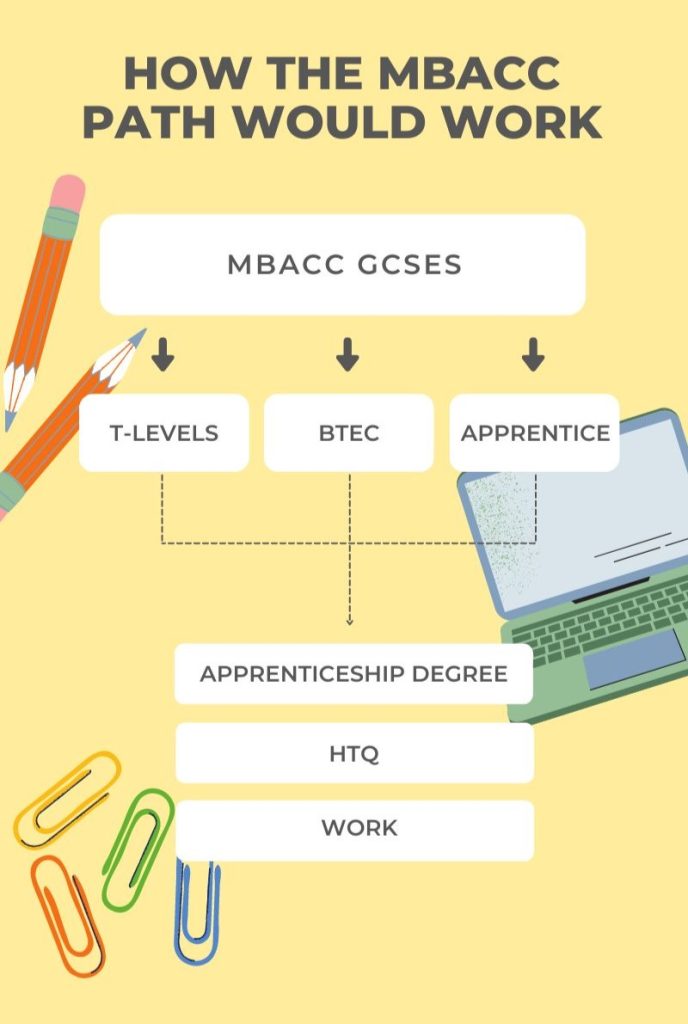

A pupil who completes their MBacc will have a number of options open to them, including technical A-levels (T-Levels), BTEC qualifications or an apprenticeship.

These could then lead to an Apprenticeship Degree, a Higher Technical Qualification or into work.

On top of introducing the MBacc, the GMCA have plans to expand the Greater Manchester’s Apprenticeship and Careers Service (GMACS).

There are ambitions by the council to transform the platform, where jobseekers can find apprenticeship schemes and entry-level positions, into the technical equivalent of UCAS, the university platform.

Why is this happening now?

The MBacc changes are only possible because of the new devolution powers given to Manchester in the national budget on 21 March.

Jeremy Hunt’s budget entitled Burnham to a single pot of cash, instead of setting out limits in spending for different areas of governance.

This means the GMCA now has more freedom to decide how and where money is spent.

In this case, the mayor appears to have freed up finances to focus on education.

What does it mean for schools?

The MBacc was announced in the midst of ongoing salary disputes between teacher’s unions and the government.

Changing priorities and hiring technical staff could consequently present a major barrier to Burnham’s project.

Equally, the EBacc will still be the national performance measurements of schools and the mayor has stated that he has no interest in ‘competing’ with the current league table system that ranks schools by their EBacc attainments.

This has led voices from the sector, such as the FE Week, to raise concerns about how the GMCA will incentivise offering the MBacc options.

Why has Burnham’s move been considered ‘controversial’?

The MBacc was not greeted with much enthusiasm by the current government.

When MM reached out to the Department for Education, a spokesperson said: “Our reforms to post-16 qualifications are simplifying the system, providing a clearer choice of all the high-quality options available to young people including new T levels alongside A Levels, and creating a level playing field.

“Introducing a separate system or Manchester Baccalaureate would undermine this progress, create an unequal system and narrow the opportunities available to young people.”

The announcement of the MBacc also reportedly caused tensions between Andy Burnham and the Labour party, though Keir Starmer claimed in an interview with the Bury Times that he was “supportive of Andy’s programme”.