Greater Manchester Police have dealt with almost 60,000 reports of missing people in the last two years, new data has revealed.

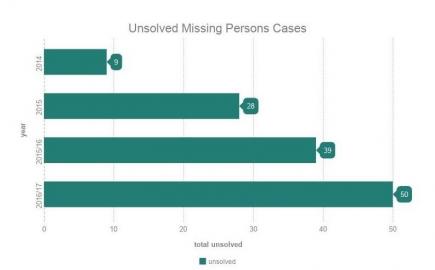

Of those cases, revealed after a Freedom of Information request by Mancunian Matters, 89 remain unsolved.

The latest figures, for 2016/17, show an increase of around 26% from the year before.

The reasons why people go missing are varied, and in some cases several factors may contribute to a person’s disappearance.

However, research collated by the charity Missing People has shown that, nationally, up to 80% of people who go missing may be experiencing some form of mental health problem, the most common problems being depression and anxiety.

This indicates that mental health problems are more prevalent in people who go missing than in the general population.

While more research needs to be done to determine the relationship between missing people and mental health problems, the link between the two is clear.

GMP attributes the rise in reports of missing people to better recording practises and a greater awareness of the risks involved when a person is reported missing.

Speaking to MM, a spokesman for GMP said: “Looking at the number of cases both active and closed, it’s evident that [the rise in missing people reports] can mainly be attributed to the greater awareness of the risks involved when people are not where they are expected to be, not only by police, but also by partner agencies including the social care systems for adults and children.”

Research carried out by the National Crime Agency has also shown that, in 2015/16, just under half (44%) of the total missing incidents were attributable to repeat individuals – people who have been reported missing on more than one occasion.

While a study conducted by the Centre for the Study of Missing Persons at the University of Portsmouth found that private care homes made up over half of locations from which people went missing in that area alone.

Susannah Drury, Director of Policy and Research at Missing People, said: “When someone goes missing it is nearly always a sign that something is wrong. The high number of people, especially children, who are reported missing more than once, shows that it is crucial to have a framework in place to prevent people being vulnerable to harm by going missing again and again.”

Research across Greater Manchester shows that 95% of young people identified as being at risk of Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE) went missing on more than one occasion.

So, if up to 80% of missing people have some form of mental health problem, almost half of all people who go missing are repeat individuals, and a majority of cases come from care homes, is enough being done to provide support to those in care?

The GMP spokesman added: “Safeguarding vulnerable people is a priority for officers and with information sharing and improved practices among partners, such as medical and mental health agencies and partners from the third sector, we are given increased opportunities to implement the most appropriate measures to find missing people and do everything we can to ensure they are safe and well.”

In response to the recent growth of missing persons reports, the charity Missing People said: “Some growth may also be linked to more people being in crisis and feeling they have no option but to run away due to the reduction in support services, for example community mental health services.”

Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham’s plan to end rough sleeping in the region by 2020 includes ‘expanding mental health and rehabilitation programmes across Greater Manchester, including re-building community mental health support’, which hopefully will go some way to being precautionary measures, instead of reactive.

Addressing the number of repeat missing persons, the charity said: “This pattern highlights the importance of agencies working together to provide the right support for these vulnerable people to help stop the cycle of them going missing again and again.”

However, while the link between mental health and people going missing, rough sleepers and homelessness is yet to be defined, it is clear that victims would benefit if mental health support was more widely available earlier, especially to those in care, as a preventative course of action rather than as a result of an issue developing to crisis point.