National Stress Awareness Week aims to highlight stressful experiences and raise stress management – but what exactly is stress and what causes it? And what can we do to limit it? We look at what happens to our bodies when we feel stressed.

How stress works

You’ve just missed the bus. You’re going to be late for work. Don’t panic, you tell yourself, there’s nothing you can do. But it’s too late, your amygdala (a small node like part of the brain which contributes to emotional processing) has registered the stress of the situation and sent a messenger pigeon to your hypothalamus. Your heart rate elevates as hormonal changes send signals to your sympathetic nervous system. Panicking seems inevitable.

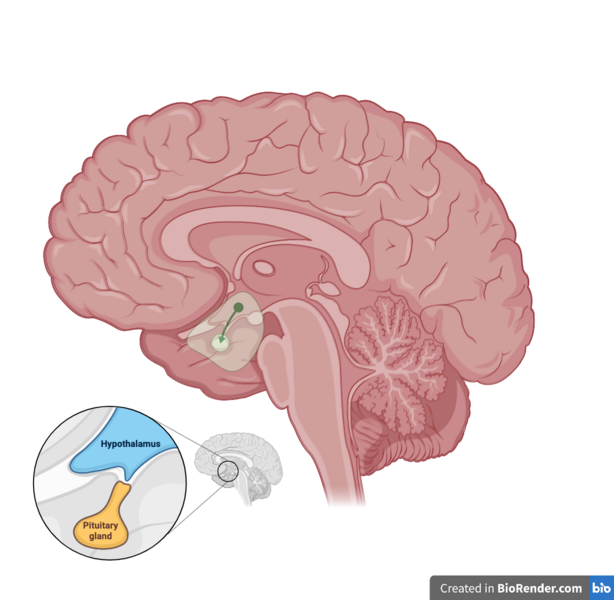

This series of events happens on some level every time you encounter stress. When the amygdala continues to perceive a threat for a longer duration – perhaps the next bus is half an hour away – the hypothalamus goes one step further and activates the HPA axis.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is a communication system between the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands. These three organs work collaboratively to manage your hormones, regulating stress in the body.

The key hormones involved in the body’s stress response system are epinephrine, corticotropin-releasing hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol.

Everyone responds to stress differently as genetics, early life experiences, environment and age all have an impact on individual experience.

Although reacting to stress is important, research has shown that consistently elevated levels of cortisol can have a negative impact on your physical and mental health.

So how can you combat stressors in your life and prevent chronic cortisol levels?

Managing stress

The NHS recommends a range of ideas, from being active and challenging yourself to helping others.

The key to managing stress and preventing long term damage to our bodies and minds is to minimise activity of the HPA axis loop.

When you go for a run, for example, two things happen. Your stress hormones are reduced and endorphin production increases. The “runner’s high” is a real neurochemical response to exercise. But don’t worry if running isn’t your thing – most exercise results in a similar bodily reaction.

Similarly, sleep is a contributing factor to cortisol levels in your body and in activating the HPA axis.

As you sleep your body naturally reduces cortisol levels with minimum production of the hormone at around midnight. Cortisol levels begin to rise again gradually until your alarm clock sounds – if everything goes to plan with your sleep schedule.

When you don’t get enough sleep and this hormonal change is interrupted, the HPA axis is triggered as the body registers your lack of sleep as a stressful situation, and cortisol levels are elevated.

Research suggests maintaining a regular sleep schedule or winding down routine, spending less time on your screen before bed and breathing exercises can all help improve your quality and quantity of sleep.

This Stress Awareness Week lower your cortisol levels by going to a yoga class, making time to bake a cake and prioritising sleep.

Feature image: Workplace stress illustration. Copyright ciphyr.com and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence