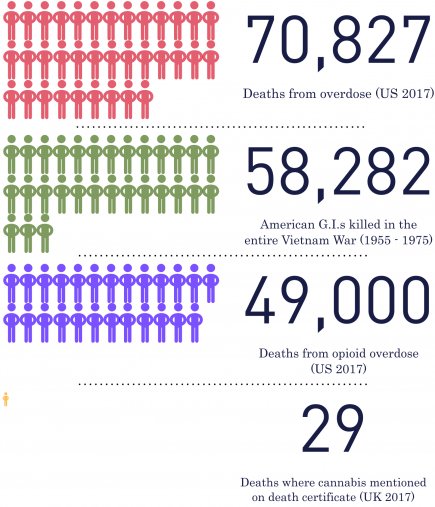

There are 58,282 names inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington: the name of every American G.I. that died during the entire 19-year span of the Vietnam War.

Yet, in one year, this number of American deaths was greatly outdone. What was the cause? Not war, or guns, but drug overdose.

In 2017, 70,287 deaths were attributed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention to drug overdoses with the vast majority being attributed to opioids.

Of the 49,000 opioid deaths, many are attributed to legal prescription drugs.

Co-codamol. Oxycodone. Tramadol. Naproxen. Fentanyl.

In the UK you may only have a passing knowledge of these drugs if you or someone in your life hasn’t had a chronic pain issue.

Their prescription in the UK is becoming more common and this fact is concerning many doctors and academics, particularly when medicinal cannabis is proving to be safer and more effective at treating conditions where opioids are traditionally prescribed.

Medical practice in the UK has seen a significant and continual increase in the prescription of opioids over the last twenty years.

Researchers for the British Journal of Pain, Clinical Pharmacist and the British Journal of General Practice found that the prescription of tramadol has increased tenfold since 1994. Co-codamol prescriptions have almost doubled since 2001.

The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) published a report in June 2019 that analysed the rates of use of opioids in 25 of its 35 member countries. They found that opioid prescriptions and use in the UK is increasing at a faster rate than 22 of the other analysed countries. The only places where opioid use was expanding faster are Israel and Slovakia.

Speaking to the BBC, lead OECD researcher Christian Herrera described this expansion in use as a “warning sign” indicative of what happened in the US that has resulted in alarming overdose death rates due to opioid use.

Meanwhile, only 29 deaths were logged by the Office for National Statistics in 2017 where “cannabis was mentioned on the death certificate”; none of these were from overdose or strongly attributed the death to cannabis use.

With these statistics coming out of the US, why is it that prescription of these dangerous drugs is becoming more commonplace in the UK?

Why is it that even though cannabis has been legalised for medicinal use, it is still kept out of patient’s hands when its safety is irrefutable?

One of the physicians and academics at the forefront of trying to answer and change this is Professor Mike Barnes.

In his 30-year career, Prof Barnes has held posts with the Royal College of Physicians, the World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation and The University of Newcastle, but most recently his work has focused on ensuring medicinal cannabis becomes a widely offered treatment as chief medical officer for European Cannabis Holdings and director of education at the Academy of Medical Cannabis.

In May of 2016, Prof Barnes co-wrote and presented a report for the All-Parliamentary Group on Drug Policy Reform, a report that was critical in the government’s decision to finally make cannabis legal to prescribe in 2018.

He’s since most famously been involved in securing a medicinal cannabis licence for Alfie Dingley, the seven-year-old epileptic boy who had to fight for access to life-changing medicinal cannabis treatments.

Though Dingley’s gone from having 150 seizures a month to zero on account of these medications, Prof Barnes sees getting cannabis to epilepsy sufferers as only part of the battle; a major fight is taking place to try to and get cannabis to patients who are otherwise being made to take killer opioid drugs with alarming regularity.

DEAD: The Vietnam veterans war memorial (Photo: Gabriel Bell)

This is particularly true for chronic pain sufferers who are kept on a continuous stream of high doses of Oxycodone and Fentanyl patches.

At the time of writing, patients struggling to get access through the NHS but want cannabinoid treatments have very few options; there are three private clinics set up by Prof Barnes in Manchester, London and Birmingham.

The first clinic of the three was opened in Manchester in March 2019 but solely focuses on the treatment of chronic pain. Birmingham’s focuses on neurological disorders whilst London’s provides alternative cannabis treatments for pain, neurology and psychiatric disorders.

If you can’t get access or more importantly afford the treatments on offer at these private clinics, you’ll have to remain on whatever NHS treatments are available and these are likely to be opioids.

I asked him what factors kept the NHS in this dangerous descent towards a US style opioid crisis, especially when government legislation provides the space for cannabis treatments to be readily available.

“The main over-riding problem is doctor education,” said Prof Barnes. “The other main negative is the guidelines from the Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Neurology Association which are unnecessarily restrictive.”

He discussed steps being taken by the Medical Cannabis Clinicians Society who have produced their own guidelines that give a more accurate picture of medicinal cannabis’ uses.

They chart conditions where cannabis was found to have “conclusive and substantial”, “moderate” or “limited” evidence as a useful treatment.

Among the conditions in the “conclusive or substantial” category are spasticity, pain and chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting: conditions treated regularly with opioids both stateside and here in the UK.

According to Prof Barnes, much of this comes down to convenience and an archaic view of what constitutes evidence.

In October of this year, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) will be publishing updated guidance for physicians.

This could be a landmark moment in which guidance leaps forward with legislation to stem the tide of opioids in support of cannabis treatments. Unfortunately, this is unlikely.

“[NICE] need to broaden their view of the evidence. It’s a different situation from most drugs. Most drugs that you don’t know much about, it’s just one single molecule which you can compare to a placebo but you don’t with cannabis,” said Prof Barnes.

“Cannabis has been around for centuries and we, therefore, know an awful lot about its side-effect profile and its safety. It’s not a typical pharmaceutical medicine; it’s a plant, a family of medicines. You’ve got a highly complicated plant with thousands of different strains and subtleties all of which have slightly different properties that affect people in slightly different ways.”

CAMPAIGN: Professor Mike Barnes (third from right) presenting the report on cannabis at 10 Downing Street in May 2016 (Photo: United Patients Alliance)

Describing cannabis as a “trial and error” medicine in which patients will be given cannabinoids with different properties based on what works, Prof Barnes sees this as a crucial point as to why his colleagues find the prospect of its use so disquieting: it necessitates a complete shift in how they view pharmaceutical medicine.

Even with the known dangers associated with opioids, it is easier to keep prescribing these single-molecule medicines than to prescribe complex and differing strains of cannabis.

Prof Barnes said: “You often have to try two, three, four strains before you get the right result for that individual. Many doctors feel that cannabis is cannabis and if you try it and it doesn’t work, that’s it. This is not the case. It’s personalised medicine.”

According to Prof Barnes, 25% of opioid deaths can be avoided by prescribing cannabis. In America, that saves over 12,000 people a year. In some cases, people can entirely replace the use of opioids with cannabinoid treatments.

For others, the use of cannabinoids can greatly reduce the amount of opioids they have to take and dramatically reduce the risk of overdose.

In the UK, we have the information and knowledge to avoid the public health epidemic we are currently on course for. NICE are presented with a clear opportunity in October to take steps to apply the work of Prof Barnes and others that may be critical in avoiding a British opioid crisis that apes that of America.

Will NICE take the steps to avoid the impending crisis? To quote Prof Barnes: “I’m not holding my breath for the guidelines to make a blind bit of difference.”