Crime has fallen year-on-year over the last decade according to official figures – yet when asked most people do not feel safer and do not believe crime has fallen.

In fact, 60% of people actually think that crime has increased over the last few years (2010/2011 British Crime Survey).

However, two in ten reported crimes go unrecorded by police, according to the police watchdog’s latest report.

In Greater Manchester, a THIRD of reported incidents investigated by the watchdog were not recorded as crimes by Greater Manchester Police – despite all being classified crimes by the watchdog… and those who reported them.

Could these discrepancies mean that the public have lost faith in the statistics?

It seems that the public simply don’t believe the statistics. Should we?

How crime is measured

Crime is basically measured in two ways – the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and police recorded crime data.

The CSEW is a survey of around 35,000 resident householders and provides a measure of the level of crime actually experienced by people and their perceptions of crime.

The CSEW estimates there were 7.5million incidents of crime against households and resident adults, down 15% compared with the previous year, 25% lower than in 2007/08 and 60% down on 1995.

The second set of figures – police recorded crime – is a measure of those crimes reported to the police and then recorded by them.

Since the introduction of the new recording rules, police recorded crime also shows a decrease between 2002 and 2013, falling by over a third.

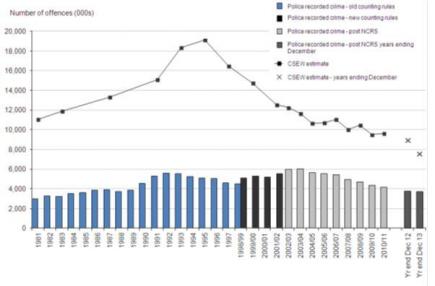

Trends in police recorded crime and CSEW, 1981 to year ending December 2013 (Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales – Office for National Statistics, Home Office)

Both sets of data show crime deceasing, but police figures over the last ten years show crime falling faster than the CSEW.

One reason for this may be that police are failing to record crime accurately.

In other words, people experience crime, report the crime to the police, but police then fail to officially record this as a crime.

In the latest two years for which figures are available, data show that only 68% of reported crimes are being recorded as crimes by the police – is this why 60% of us do not believe crime is falling?

In fact 34% of the public say they distrusted crime figures, although the police were most trusted to present crime figures in a fair and balanced way and politicians were least trusted.

One possible explanation for the discrepancy between people’s perception of crime and police recorded crime is put forward by the ONS (Office for National Statistics) who say that it may be due to ‘a gradual erosion of compliance with the NCRS (National Crime Recording Standard), such that a growing number of crimes reported to the police are not being captured in crime recording systems’.

Data collected by individual forces are fed through to the ONS where they are published every quarter.

Interestingly, in 2012 the UK Statistics Authority, whose main function is to ensure that official statistics serve the public good, removed police-recorded crime data from official national statistics records because of their concerns about its accuracy.

‘Serious concerns’

This issue was investigated by the HMIC (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary) who found that 20% of reported crimes are not officially recorded by the police

In their interim report Crime recording: A matter of fact, the HMIC said: “We are seriously concerned at the picture which is emerging. It is one of weak or absent management and supervision of crime-recording, significant under-recording of crime, and serious sexual offences not being recorded (14 rapes).

“Some offenders have been issued with out-of-court disposals when their offending history could not justify it, and in some cases they should have been prosecuted.”

The HMIC report concludes that under-recording of crime is due to a number of factors including poor knowledge of the rules and inadequate or absent training in their content and application; poor supervision or management of police officers; and pressure of workload.

Police and crime commissioners plans invariably contain commitments to reduce crime and to do this crime data must be accurate and yet the HMIC report concludes that police recorded crime date lacks the necessary reliability.

The HMIC found that of the 388 incidents they investigated in Greater Manchester, all of which should have been recorded as crimes, only 265 of these were actually recorded as crimes.

In other words, a staggering 31% of crimes were improperly recorded by Greater Manchester police, denying victims justice and allowing offenders to escape detection.

Across the country HMIC inspectors found that out of 3,102 incidents scrutinised only 2,028 were recorded correctly.

Among the incidents that were not recorded there were a number of serious crimes such as sexual offences (including 11 rapes) and crimes of violence, robbery and burglary.

The HMIC conclude that police are not properly recording incidents due to a range of factors including police not investigating fully every report and poor-decision making regarding the classification of incidents.

Another major concern is the police procedures and practices of no-criming – not all incidents reported to the police turn out to be crimes and they are therefore allowed to re-classify it as a no-crime.

The HMIC give the example of someone reporting a man on a ladder breaking the first floor window of a house and climbing in. A police patrol immediately goes to the house and finds the man who is inside is the owner and had forgotten his key.

When there is such an incident, or when the police have clear evidence to believe that a crime has not been committed, this is not a crime and not recorded as such.

In this case police have clear evidence that the incident was not a crime but in many cases the HMIC have found instances where police are no-criming incidents when they should not do so.

In Greater Manchester, the HMIC audit found that out of a total of 91 no-crime decisions they reviewed, only 65 were correct – nearly 30% of crimes reported to the police were incorrectly reclassified as no-crimes, again failing victims and allowing offenders to escape justice.

Typical errors in no-crime decisions arise simply because the police do not believe the victim and so do not investigate further and incorrectly decide to no-crime the report.

Community resolutions

The report also found that out-of-court disposals were often not being used in accordance with national guidance.

Out-of-court disposals are supposed to allow police to deal quickly and proportionately with low-level offences.

They include issuing cautions when offender’s behaviour requires no more than a formal warning, on the spot fines (a penalty notice for disorder) and community resolution.

Community resolution is dependent on the offence that has been committed; it may include, for example, simply apologising to the victim or making good damage caused – these generally only occur when the victim agrees there should be no formal action.

Community resolutions can be offered when the offender admits the offence and are mainly used in cases where the victim has agreed that he does not want formal action to be taken.

Inspectors found in many cases an offender’s previous criminal history should have precluded the use of an out-of-court disposal and also that the wishes of the victim had not been considered – in these cases the use of a community resolution was not appropriate.

The HMIC concluded that the main reason for under-recording of crimes or the inappropriate use of no-criming was poor training and a lack of understanding of the correct procedures.

Image courtesy of GMP via YouTube, with thanks.