A number of days have passed since the hope of a progressive country that protects its most vulnerable and funds the basic social systems required in order for its citizens to survive was consigned to history.

On December 12 2019, for the many Labour voters emboldened by politics of Corbynism, the vision of a compassionate, progressive and equal Britain died.

The following morning was a Friday the 13th that would live up to the billing that those of a superstitious disposition have oft profesised. For once, the naysayers were right. For Friday 13th December was the darkest of days in Britain’s recent and most troubling, history.

It was the first day of a post-hope era.

So, let’s get all the cliches out of the way early. The Brexit culture war had been won by Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson and his chums and the turkeys, in the first December election in living memory, had voted for Christmas.

Cliches such as these, in other circumstances, would perhaps be a succinct, insightful way of articulating an otherwise complex series of events. However, it was this sort of facetiousness that had alienated the working-classes in the hinterland towns left isolated by what they clearly perceive to be the metropolitan elites in the first place.

The dismantling of the working-classes is often attributed to the centralisation of the British economy under the Conservative rule of Margaret Thatcher.

The cast-aside mining towns of Yorkshire, the Midlands and Wales and the docking communities of Liverpool, Glasgow and Tyneside immediately spring to mind when one casts an eye back at a time when class was deemed an irrelevance.

Famously, Thatcher didn’t believe in class. Rather, or so she contended, such a notion was simply a creation borne out of Marxist militancy.

The sloganeering of an Alastair Campbell-steered New Labour, to his many detractors, had long been deemed a corny vestige of a past which had promised much and delivered little to the communities who needed it most.

However for all the wisdom of Guardian columnists that forewarned of a lurch to the right in British politics – something unthinkable in the early days of the glossy, smiley New Labour – it was three words that would reduce the Labour Party to its worst showing at the polls since before the Second World War.

If there is one image that will undoubtedly find its way into the history books of the future as a standout microcosm of this election, it will be one of Boris Johnson standing in front of three-words: ‘GET BREXIT DONE’.

It is interesting that policy no longer seems to sway voters. A gaffe-laden campaign from Johnson which included numerous attempts to avoid scrutiny that began with his dodging of an interview with the BBC’s Andrew Neil and concluded with him hiding in a fridge to avoid the inspections of the presenters of ITV’s Good Morning Britain, some of the former Mayor of London’s ill-advised exertions during this campaign alone made Gordon Brown’s ‘Bigotgate’ look decidedly tame.

Seemingly, voters no longer trust politicians to enact these promises anyway – Labour offerings of a fully-funded NHS, nationalised railway and wi-fi and investment in public services, despite widespread support, were not enough to make Leave voters back the policies of Corbyn and McDonnell.

The Labour Party even produced so-called ‘local manifestos’ which outlined how they would restore the communities that had been left behind under Thatcher and New Labour. The vow to bring investment to towns in Britain’s metropolitan hinterlands through better transport links and the roll out of high speed internet clearly simply failed to register with voters who, perhaps, seemed wary of voting for a party of hope and progression.

In these towns, it seems, there is no longer a belief that Westminster politicians can deliver this.

Just as ‘MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN’ had done for Donald Trump in the United States; ultimately, ‘GET BREXIT DONE’ would be enough to swing voters in the towns that had been changed forever, and not necessarily for the better under Thatcher, from Labour Red to Tory Blue.

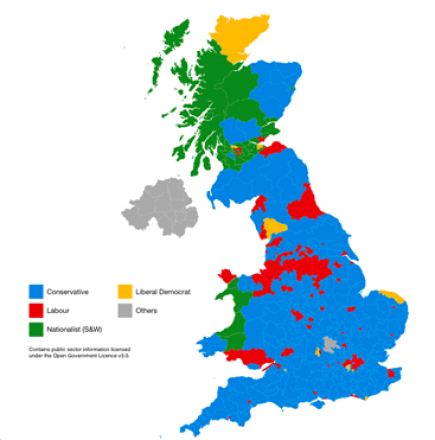

For any Labour voter old enough to even recall the days of Blair and Brown, the UK constituencies map that first emerged in the early hours of Friday December 13 2019 must register as a nothing short of dystopian.

The final embers of Gordon Brown’s doomed stewardship of the UK through the stormy waters of the worldwide financial crash of 2008 may have settled only nine years ago. Public distaste surrounding Britain’s entry into the Iraq War in 2003, coupled with the need for someone to blame for the ‘boom and bust’ economy that New Labour had overseen as a government during their 13 years at the helm, probably left their case for forming the next government damaged and broken from the outset, in retrospect.

The coalition of the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats would sound the death knell on what many political observers had called the ‘form realised’ when Tony Blair entered Number 10.

Famed historian Fukuyama dubbed the politics of the 1990s as representing the ‘end of history’- the admittedly Whiggish implication being that the left-leaning Neo-liberalism of Clinton and Blair would represent the epitome of progress in terms of political policy.

It may look hubristic now but for thinkers such as Fukuyama the emergence of the nationalistic right-wing administrations of Trump and Johnson were, quite simply, never meant to happen.

Such notions now seem regrettably quaint.

Thursday’s General Election took place little more than nine years since Gordon Brown departed Downing Street for a final time, however, that now feels like a lifetime ago.

Thatcher may be dead but her rhetoric of the ideas of ‘society’ being no more than mere illusion is alive and well in the towns her own policies left behind.

Thatcherism may have reduced working-class communities in the North of England to breaking point, however, it is clear that many in those areas feel for all the front of New Labour’s vows to piece such communities back together again; little was achieved.

Whether metropolitan Labour supporters feel the narrative that the governments of Blair and Brown achieved little in these towns is wrong is, frankly, irrelevant. Undoubtedly, this is how voters in these towns feel and, ultimately, this disconnect would fatally cost Labour in last Thursday’s General Election.

The former mining towns of Workington in Cumbria, Blyth in Northumberland and Bolsover in Derbyshire will be spoken about for years to come when historians ponder the question of just how the unthinkable – the fall of Labour’s once-indomitable Northern ‘Red Wall’ – had occurred.

The latter particularly resonates with me as the dust begins to settle on a dismal few days for Labour. Dennis Skinner, a former pit-worker, a man who held this seat since 1970, had become part of the political landscape.

Affectionately known as the ‘Beast of Bolsover’ as a result of his impassioned service to his Derbyshire constituency, stretching back nearly five decades, the Beast of Brexit would ensure his seat would fall into the hands of the same party that rendered his constituency economically obsolete in the days of the monetarist government of Margaret Thatcher.

He would thank nobody for suggesting he had become part of the Westminster furniture, in fact, he would unquestionably resent such a notion of entitlement, so I will refrain from entertaining such a notion.

However, on Thursday, the Westminster veteran of 49 years, at the age of 87, would finally lose his seat. His finger-pointing, embittered defence of the miners during the days of Thatcher may divide opinion but, surely, it wasn’t meant to end this way for a man who had committed, with such honour, the majority of his adult life to his constituents.

What’s more, he would lose his seat to a Conservative, Mark Fletcher. Maybe the memory of Thatcher no longer burns as bright as some of us believe. That much is clear following the loss of seats such as Bolsover.

And, in many ways, this is why so many Labour voters, including myself, now feel so wounded; it is as though all everything we once took as gospel has been dismantled by the propaganda machines of Nigel Farage and Dominic Cummings and, on the morning of Friday 13th, suddenly the Britain we once knew, had transformed into a country we no longer recognise.

Wasting no time in letting the dust settle on Labour’s resounding defeat, within days a new splinter group had emerged, a curiously named faction called Blue Labour.

Such a concept has existed from the days of Blair’s government, however, as their oxymoronic name would perhaps suggest, they have struggled to find a discernible position in the political landscape in Britain until now.

Over the weekend, the pressure group have vowed to deliver ‘a socialism which is economically radical and culturally conservative is the future of the Labour Party’. Frankly, this notion sent shivers down my spine like Boris Johnson hiding from GMB in a fridge. It is no laughing matter, of course, but after the last few days, perhaps as the old adage goes, if one didn’t laugh, they would cry.

Jonathan Rutherford, who has been described as one of the movement’s “leading thinkers” claimed that the results of the election had left their protestations against Labour’s shift towards the socialist left under Corbyn ‘tragically vindicated’.

It is clear that Blue Labour feel their opportunity for political relevance now knocks. For them, the so-called ‘Brexit Election’ – as it was dubbed by shadow chancellor John McDonnell following the exit poll that emerged on the night of the election on Thursday – has given them a mandate to push for Labour to embrace what they are terming ‘culturally conservative’ values.

This presumably means a tougher stance on issues such as immigration and Brexit. Such language is alarmingly vague and a stark departure from the progressive overtures of Corbyn’s campaign.

It is worrying that ‘culturally conservative values’ could suddenly become a political device and, for Remainer Labour voters such as myself, such a lurch into what I can only deem to be the cultural past as opposed to the present, seems like an almighty show of selling-out at a time when defiance is so pivotal.

It’s time for Labour to stand by their basic principles. A move towards the centre in terms of economic policy is seen by some as the only way forward, which is a debate those from across Labour’s wide-Church must now be willing to embrace, and Keir Starmer, in this respect, seems to represent a safe pair of hands that may go some way to reuniting a party that was so split for periods under Corbyn.

For now, the emphasis must, rather, be placed in ensuring that the values upon which Labour has always stood for – tolerance above all else – is maintained.

Perhaps for a party that has lurched between the camps of Neo-Liberalism and socialism during the past 20 years, it may be time to face the tough reality that within the party, Labour is now facing a very real identity crisis.

Only time will tell whether the results of this election, including the puncturing of Labour’s once impenetrable ‘Red Wall’, were simply a reflection of the Brexit culture war. There seems to be a strong argument to suggest it may be.

However, Labour’s next step is crucial. For all Corbynism achieved in its undeniable enfranchisement of 18-25 voters, it appears that its traditional support is hanging by a thread.

What is for sure, regardless of whether the party moves central or sticks with socialism, the adoption of so-called ‘cultural conservative values’ would undoubtedly alienate the voters they still have left.

Labour must now ensure that, in trying to claw back it’s ‘Red Wall’ support, it does not lose everyone else in the process.

Image courtesy of ITV News via YouTube, with thanks.