Human zoos containing ‘freaks’, dwarves, albinos and black people existed in Manchester as recently as the late 19th century, MM can reveal.

And last week two Norwegian artists hit headlines when, as part of celebrations to honour the country’s 200th anniversary of the constitution, they were awarded government funding to re-enact one to highlight the country’s racist past.

In 1885, the ‘Scramble for Africa’, the annexation of vast swathes of African territory by European powers, was well underway.

At the same time, human zoos, called ‘anthropological exhibitions’ back then, became increasingly popular across Europe as thousands flocked to see the demonstrations of exotic people put on by entrepreneurs.

These exhibitions toured the largest cities including London, Paris, Berlin, New York and it appears that one also found its way to Manchester.

Terry Wyke, senior history lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University, told MM: “Leisure entrepreneurs, of whom the German Carl Hagenbeck was probably the best known, arranged for whole ‘tribes’ to be displayed living and working in exhibitions, wearing their native costumes, singing and dancing, which people paid to visit and observe.”

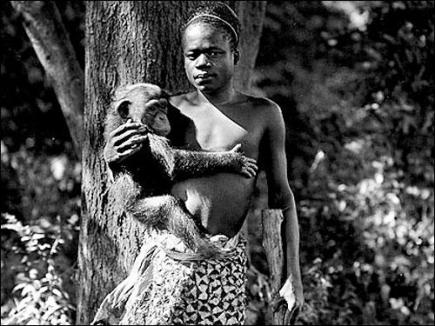

HUMAN EXHIBIT: Ota Benga, 23, brought from South Central Africa

It appears that 19th-century Mancunians were also eager to observe the ‘natives’ of the countries their government were colonising – and not just Africans.

“Hagenbeck brought his Ceylonese village to Manchester in about 1885-6,” Mr Wyke said.

“They were displayed for the instruction and amusement of Mancunians at Pomona Gardens, one of the last big shows there before it went under the shovel [it closed in 1888].”

Pomona Gardens was sited around 1.5 miles south-west of the city centre, between the River Irwell and Hulme, and contained a hedge maze, camera obscura and archery ground.

It was also home to Britain’s largest music hall, the Royal Pomona Palace, which could accommodate at least 20,000 people.

Mr Wyke explained that it wasn’t just people who were considered the stars of the shows, but so were exotic animals.

He said: “The natives included dancers, snake charmers and musicians and so on, but the real stars of the show were the elephants.”

“‘Freaks’ were a staple entertainment in the travelling shows that called in at Manchester in the early nineteenth century.

“Had you visited the saturnalia that was the Knott Mill Fair in the 1830s you would have paid money to see – and possibly touch – dwarves, albinos and black people.

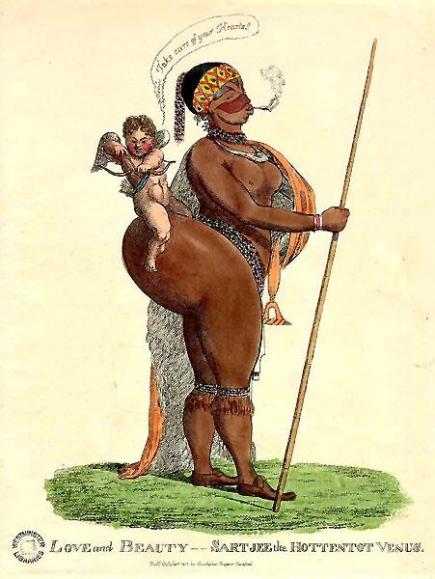

“The Hottentot Venus is famous and has been the subject of books and plays, and if she did not visit Manchester herself then I am pretty certain that one of the other Hottentot Venuses who travelled with the fairs would have done so.”

The ‘Hottentot Venus’ was the name given to a number of Khoikhoi women, taken from South-West Africa and exhibited across Europe – the most famous of these, Sarah Baartman, was shown in Britain for four years from 1810.

VISITOR ATTRACTION:Caricature of ‘Hottentot Venus’ Saartjie ‘Sarah’ Baartman

The later exhibitions put on Hagenbeck and his contemporaries were designed to entertain the public, but were also used to justify imperialism as it was believed to bring ‘civilisation’ to the ‘savages’ and theories of Social Darwinism.

Ethnographic collections were used for these purposes right up to the Second World War after which point attitudes finally began to change.

It is this dark past that the Norwegian artists Mohamed Ali Fadlabi and Lars Cuzner seek to highlight through their ‘human zoo’ re-enactment but the project – which is to exhibit volunteer ‘inmates’ – has already polarised opinion.

Ian Thomas, a director of Black History Month who, until recently lived, in Manchester, told MM: “I don’t see any problem with it – it’s not racism, it’s highlighting historical racism.

“It’s good that this project has provoked debate and raised awareness. However, I don’t think this is an issue, nor is it in bad taste.”

On the other hand, a note of caution comes from Manchester’s historians and anthropologists.

Dr Ian Fairweather, lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Manchester, said the Norwegian project could backfire.

He said: “There’s always a risk in reproducing categories in order to challenge them, but there are better ways to do it.

“For example, a psychology experiment, segregating people by eye colour, that sort of exercise. You could create a human zoo without exhibiting Africans, and then bring race into the discussion.”

He added that the two artists were vulnerable to criticism similar to that levelled at the organisers of an African cultural festival held in a zoo in Augsburg, Germany, in 2005 with all of the connotations that location entailed.

His concerns were echoed by Stephen Welsh, curator of living cultures at Manchester Museum.

“With a project like this you have to do extensive community engagement, across the board,” he said.

“You need to keep the channels of dialogue open and transparent, as your best intentions can be interpreted in many different ways.

“An exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto [Into the Heart of Africa, 1989-90] sought to critique imperialism but there was no level of engagement, so it was not perceived as intended.

“It was seen as light-hearted and poking fun at imperialism, and those who had suffered from racism did not appreciate that.”

FAMILY AFFAIR: Sisters who were exhibited in Southampton, USA in the 1800s

Another point of view came from Kathy Whalen, cataloguing librarian at Chetham’s Library, who argued that we must not be too presentist in our interpretation of these exhibitions.

She said: “Remember that the Victorians and Edwardians did not have television, which allows us to indulge our voyeuristic natures from our living rooms.

“Today we go to ‘them’, rather than bringing ‘them’ to us, but our enthusiasm to gawp remains undiminished.”

Attitudes towards race and ethnography have changed considerably since the 19th century, when Mancunians were eager participants in British imperialism.

However, the ‘other’ will always hold a fascination for us, whether in ‘anthropological exhibitions’ or on shows like Embarrassing Bodies and My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding.

Perhaps the Norwegian artists’ ‘human zoo’, for all its potential pitfalls, will go some way to demonstrate that we are not so different from the curious visitors to Pomona Gardens in 1885-86 after all.