Beth said it took ten minutes for the DMT to infuse into her blood.

In the room with her: two psychiatrists, two therapists, two nurses.

This was Beth’s second day in the clinic, and it had taken several rounds of medical screening to get to this moment. It was important that she was psychologically stable enough to withstand what was about to happen.

The trip itself was over in 50 minutes.

“They say that you live your life in a tiny box and whatever’s going on inside that box is your whole world,” said Beth. “With any kind of psychedelic experience, it just opens that box a little bit and gives you a bit of a different perspective.”

She wouldn’t go into too much detail about her trip because she was concerned about influencing others’ experience of the drugs. “In some ways you might want to know what you’re getting into, but in some ways you need to just let them have their own experience.

“Mine was completely dissociative, I didn’t see entities [but] I didn’t really know what kind of being I was,” she laughed. “That’s all I’ll say on it.”

The psychedelic that had been administered to Beth was dimethyltryptamine. Otherwise known as DMT, it is the same psychoactive ingredient found in ayahuasca. The researchers running the study from the MAC institute in Manchester hope the class A psychedelic could become a treatment for major depression.

But Beth wasn’t depressed.

She was there because she’s perfectly healthy.

Beth was volunteering on a phase one medical trial. It’s the first stage in testing new drugs on humans, in which healthy volunteers – who have no therapeutic need for the treatment – are used to investigate the safe dosage and potential side effects of a new product. And they get paid to do it.

Apart from alcohol, Beth had never participated in recreational drug-taking, so she saw the trial as a chance to experiment safely. She would even do it for free.

She is 31 now and has been taking part in phase one trials for a number of years. When she reflects on the first trial she took part in, she can see a shift in her approach over time.

“Back then I think I was more financially motivated, so I was probably a little bit less interested in what the risks were,” she said.

“I did read about them. But you meet with doctors first, and they explain it in a lot of detail, and it is quite reassuring – I don’t remember having any reservations.”

One of the issues with phase one trials is that the financial rewards offered by trials can be high enough that volunteers would feel incentivised to overlook, or not properly engage with, the risks involved. For example, for the three days that it took Beth to participate in the DMT trial she received £1,700. Another study she participated in required her to visit the centre every day for 28 days, including two overnight stays – one two night and another three nights, for which she was compensated £4,500.

The latter went straight into a house deposit. “It is life-changing sums of money,” she said. Adding that she has met people who approach trials as a career, or work from the facility while they are staying there.

The payments need to be big because, in most cases, altruism just isn’t enough. There would not be sufficient volunteers, and new drugs would never it to market.

“There’s a problem about operating a fiction that this is just compensation, whereas in reality it is a payment for work.”

Professor Søren Holm is a biomedical ethicist at the University of Manchester. He said that the question of what volunteers are paid is one of the main ethical concerns when it comes to phase one trials.

“They are volunteers in the sense that they choose to participate,” Professor Holm explained. “But in most cases we could be fairly certain that those who participate, participate primarily because they’re paid.”

The payment is calculated according to factors like loss of time and the inconvenience or invasiveness of the trial. But that doesn’t negate the power of money as an incentive.

“There’s a problem about operating a fiction that this is just compensation, whereas in reality it is a payment for work,” he said.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Professor Holm said that lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to take part in phase one trials, and facilities tend to be located in cities with large student populations from which they recruit very successfully. It makes sense – a combination of very little money and very flexible schedules makes students ideal candidates.

Student populations are also distinct in the sense that their lower economic status is not associated with lack of education. In theory, this should make them better able to engage with information provided about possible risks. In other words, they are more able to give informed consent.

One way that volunteers are protected is through the ‘The Over-Volunteering Prevention System’ (TOPS). Every organisation that runs trials in the UK must register participants on TOPS, and through this database they exclude volunteers participating if they are currently enrolled in another trial or participated too recently.

The system reduces the risk of medicines interacting, and it also makes it harder to use trials as an alternative to regular employment.

Beth said that she learned the hard way not to rely on the money from a study. In the past, she has been turned away as a volunteer shortly before she had planned to participate in a study either because of a minor medical issue, or because she had been recruited as a ‘reserve’.

She stressed that her experience at MAC Medical Research was a positive one, but this has not always been the case elsewhere.

Some facilities will recruit more volunteers than they need because of the likelihood of a portion of those volunteers being turned away on medical grounds. If that doesn’t happen, the ‘reserves’ are sent home anyway.

Beth said that, in the past, she has been led to believe that she was not a reserve, only to be taken out of a study at the last minute. In these instances, she was only paid for the time she had already given.

“As a volunteer you’re treated as quite expendable. There’s doctors, nurses – they’re very thorough in that way – but you feel like a bit of a lab rat,” she said.

The medical student

Laura, 21, is a medical student at Cambridge University. The studies she has taken part in at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit aren’t phase one trials – some of them an even be done online.

But like the students Professor Holm described, the £10 to £15 per hour the studies have paid her is still the main motivation.

“Cambridge are quite funny about us having jobs,” she said, referring to Cambridge’s policy of discouraging students from taking on paid work during term time. “So I don’t really make any money in Cambridge – I’ve got a job back home, but I’m not home very often. Small amounts of money here and there is good.”

She also thinks that the experiences she has had during these studies will be helpful in her career.

“If I’m sending someone to an MRI scan, I know what that’s like and it’s quite a horrible experience,” she said. “At least I can now understand why a patient might be worried about it.”

In the particular study she is referring to, Laura met with a researcher prior to the MRI. Based on the information gathered in this meeting, they read out 10 scenarios tailor-made to make Laura feel anxious. Then they watched how her brain reacted.

The risk here is not akin to ingesting a new drug, but it can’t have been particularly pleasant either. Even if it was a useful experience, Laura says she prefers studies that can be done from her laptop.

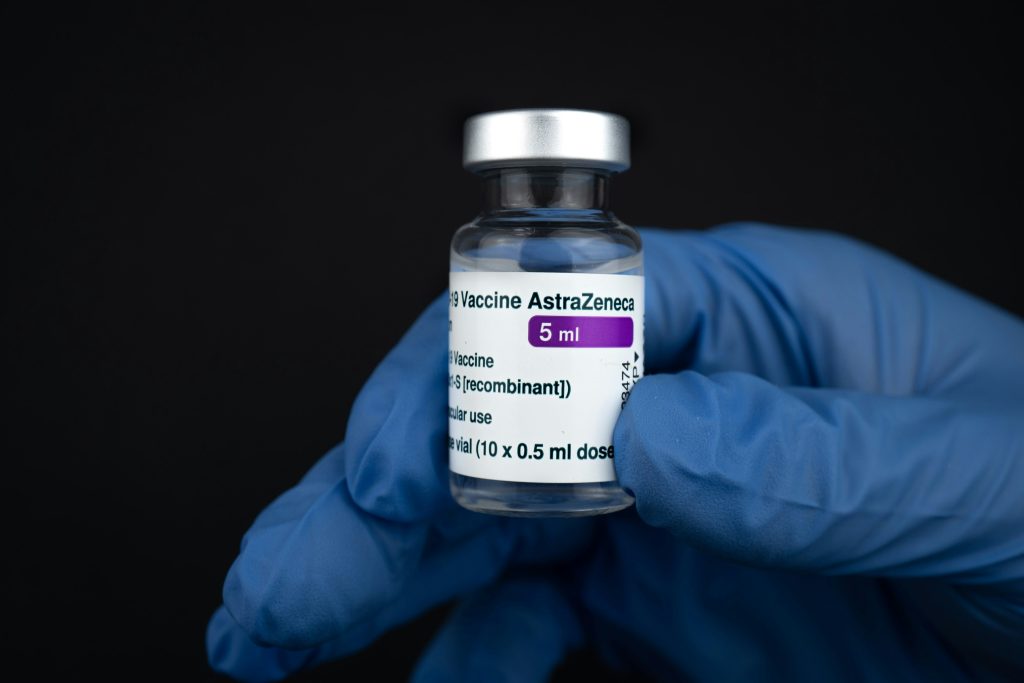

The AstraZenaca volunteer

Sarah couldn’t remember how much compensation she received when she was inoculated with the AstraZeneca vaccine in May 2020: “£20? £50?” she guessed.

“I remember the nurse saying something like: ‘Oh, you must really want to do this because this payment is rubbish’”, she said.

Sarah usually works in theatre and there was only so much she could do over Zoom. “I can’t stress how bored I was,” she said. “I just needed something to do.”

She turned to neighbourhood WhatsApp groups, but no one else needed help with shopping. Then she saw that her local hospital was recruiting for a vaccine trial.

“It was kind of selfish. There was a sense of: ‘I’m doing it for the country’, but there was no part of me that was like: ‘God, if I don’t do this, who’s going to do it?’”, she said.

“I was like: ‘Well, I’m sure this is going to be quite over-subscribed, but it will give me something to do. It’s a good way to check my health. And it also gives me early access to a vaccine.’ Because I was pretty scared of getting [Covid].”

She knew going into the trial that there was a chance she would be given a placebo. But she quickly came to the conclusion that this had not been the case.

“I was so ill the first night,” she said. “Every few hours you had to take your temperature and log it. My temperatures was really high, and it was that night that I was like: ‘Oh no, what have I done? Is this really bad?’”

Sarah’s fever subsided and the following December it was confirmed that she had received the vaccine rather than a placebo.

Overall, the experience was a positive one. It gave her structure and a sense of purpose in a period that was otherwise defined by fear and helplessness.

She said that she wouldn’t consider taking part in a challenge trial – whereby participants are deliberately infected with a disease – like the one conducted by Imperial College London the following year. But, were the same scenario to arise again, she would make the same choice.

The DMT might have worn off in less than an hour, but Beth had to stay one more night at the clinic. They needed to make sure she had genuinely returned to reality.

“They do a lot of questionnaires to make sure that that you’re feeling alright, and a follow-up call with an actual psychiatrist – they don’t palm you off with any trainees,” she said.

Irrespective of the results of the trial, for Beth, it had been a success.

Money was important. It felt good to know that she was contributing to medicine. But this was an opportunity for her to experiment too.

“When else can you take a psychedelic and two psychiatrists and two therapists literally be holding you hand while you’re doing it?”

Feature photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Some names have been changed.