Back-to-back and in black and white, the screening of Frankenstein (1931) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) was a definite Halloween treat.

Design Manchester’s film season closed off this year’s screening on Tuesday with the last two films of the ‘Reframing Reality’ series with a special double bill of the classics Frankenstein (1931) and the Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

In collaboration with the Gothic Manchester Festival, the DM17 film season had Gothic scholar and co-curator Sir Christopher Frayling introduce the screening.

With the near release of his new book ‘Frankenstein – The First 200 Years’, which heralds the bicentenary of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, the crowd was given a first-hand insight into the background of the book, plays and movies before the screenings began.

Mary Shelley was 18 when she initially told the story of Frankenstein, 19 when she turned it into a novel and 20 when it was published.

“One of the things which takes a bit of explaining is how on earth a book published on New Year’s Day in 1818, with only 450 copies for the public, made such a huge cultural splash,” said Frayling.

He went on to tell the audience how the story was made into several different adaptations and had eight different screenplay versions playing in the West End within three years of its initial release.

At a time where Intellectual Property hadn’t yet been invented, people were free to make their own dramatic adaptations.

Some authors of the day would create their own adaptation so to get a foothold in the theatre, but Shelley never did.

“The adaptations of the story, both on stage and in the movies, is what got Frankenstein into the cultural bloodstream,” said Frayling.

The first edition of the book, Presumption, although not an easy read, was a ‘subtle book’ and a huge hit.

Its outlined themes were those about a creature, pieced together from the bodies of dead people, who’s rejected by everyone because he’s strange. He was treated nasty, and therefore became nasty.

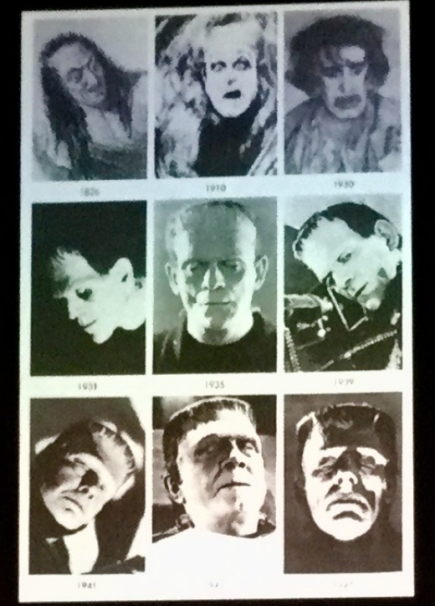

BECOMING A MONSTER: The many faces of Frankenstein over the years…

A “straight forward, melodramatic top thumper,” in the words of Frayling.

“It’s about a mad scientist who is mad from the word go, about a creature who can’t speak in the book yet can now grunt.

“From being rather beautiful in the book, where his parts are selected with great care, he’s well-proportioned with lustrous black hair.

“He’s built like a Chippendale and has been chosen with the best possible ingredients, on stage he becomes a monster.”

The screenplay also gives Frankenstein an assistant, Fritz or Igor, places his laboratory on top of a hill where you have to climb several sets of stairs to get to it, and there is a bubbling cauldron inside, implying the practice of alchemy.

These are all themes not in the original ‘pro-science’ novel.

Frayling continued to explore the different characters and looks used to play Frankenstein’s monster throughout the eras, from Michael Thomas Cook to O. Smith (the revival) showing pictures on screen and annotating them.

One of the pictures shown was of a water colour painting of the monster from a play in the 1820s.

It was the first time this photo of the painting has been seen in public since about 1822 and it depicted a bug-eyed monster rather than a ‘Chippendale’ character.

After reading a small section on the look of Frankenstein from the book, Frayling focuses on the eyes.

“There’s something about the eyes that give the game away, he’s sort of dead behind those eyes.”

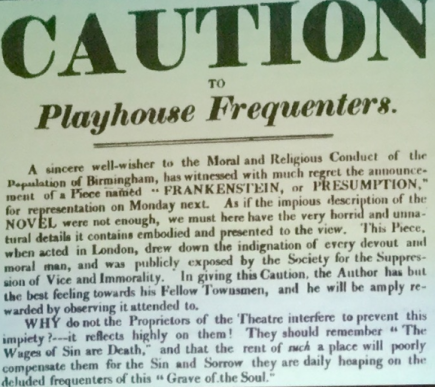

HORRID AND UNNATURAL: Frankenstein was viewed as ‘impious’ in 19th century England

The speech went on to explain that in 1831 Shelley rewrote the introduction, taking a lot of the science and complexity out of it, so the book resembled the play. It was the first proper step into making the story more manageable.

With a copyright on the novel, it was only in the late 1920s when Peggy Webling’s play version was discovered and bought by Universal Studios when the Frankenstein film came to life.

Frayling gave details about the producers, explaining their struggles in turning the three-part novel into a linear story.

He spoke about the cut scenes within the films, and hidden inspirations for certain parts, and touched on the make-up, which took four hours to do.

He ended off by showing the original ‘teaser’ poster, the first ever in movie history, as well as the original poster and spoke about how the groundbreaking film made $1million and was extremely successful.

So good in fact it made a sequel.

“One of the very few sequels in history, in my opinion, which is even better than the original,” said Frayling.

TOMORO! Sir Christopher Frayling presents James Whale’s ‘Frankenstein’ @MetrographNYC + @ReelArtPress book signing! https://t.co/KX8vSYf4uv pic.twitter.com/30YpOoYCiO

— ARTBOOK | DAP (@artbook) October 26, 2017

The back-to-back films had the audience glued to the screen, and, if not in sessions of suspense, bouts of laughter at the olden day ‘horror’ scenes.

Frayling indeed spoiled the audience by sharing his personal observations, discussed in his book, where he refers to ‘a celebration’ of Frankenstein, which added to the films.

It is one thing to be able to watch a movie and enjoy it, but a completely different thing to be able to watch a movie with an insight into the makings and history of it allowing you to appreciate it more.

Coming from a time when the plays first opened in Birmingham, where pamphlets were released by the Society for the Circulation of Vice disapproving strongly and discouraging people from watching the ‘disgusting play’, to a time where we can look upon the movies with admiration and a slight sense of humor, the evolution of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein has developed tenfold and the evening was a very big success.

Image courtesy of The Dancehouse via Twitter, with thanks.