Days before I went to see Imitating the Dog’s production of Night of the Living Dead, about the effects of an indiscriminate virus ravaging the planet, an indiscriminate virus ravaged the planet.

George A. Romero revolutionised horror cinema in 1968 when he released Night of the Living Dead, the first in a long series of zombie movies spanning more than four decades, and cementing the tropes that still characterise the zombie archetype today.

Before his debut zombie flick, the zombie was often a normal person enthralled by voodoo magic in their sleep, or under the power of a curse. They could still move at pace, and weren’t always cannibalistic.

However, Romero realised the metaphoric potential of the monster early, and would soon create what have proven the finest uses of the zombie trope, in his first two ‘—- of the Dead’ films, which dictated what the zombie would become: the ambling, brainless, flesh-eating virus victim that horror fans know and love.

I had planned to be at HOME Manchester the week that theatres were forced to close as part of the national Covid-19 countermeasures, to see Imitating the Dog’s production of the Romero classic.

Luckily, the production has been made available for audiences to stream online, with the proceeds going to a development fund for freelance artists.

In response to the Covid-19 restrictions, we’re releasing a selection of past work, including Night of the Living Dead-Remix, online on a pay-what-you-like basis. The income from this will go to a development fund to support freelance artists & practitioners to make new work1/2

— imitating the dog (@ImitatingtheDog) April 2, 2020

I spoke to the show’s director, Andrew Quick, about Imitating the Dog’s production, and what drew them to this film in particular.

“It’s been on our radar for a few years, partly – originally – because it was out of copyright, and it was a movie that I and Pete (the other director)… We liked it. We liked its themes and its politics, and the rough-and-ready way it was made, so we thought it would suit our style. Then it sort of went on the back-burner for a few years.

“So that was the starting-off point of our interest. We’ve been interested in trying to do a shot-for-shot remake of a couple of movies before, as well, one of them being Psycho, which we did a student-led version of, and it’s a great movie to do that. So, we knew it could work – though it’s very, very tough – so we joined the two projects together, if you like.

“That’s how it developed, and of course, we were always very interested in the film’s presentation of a 1960s America falling apart – and this was before the present crisis – but we thought, even with Trump’s divided America, it felt like an interesting, telling moment, to go back to this idea, of what our version of America, through the movie, might look like: revisiting the 60s, in a political moment.”

Romero’s film was produced on a shoestring budget, but with astonishing care and attention to detail. It has since been regarded as an influential classic of the genre, prompting a move away from angular sets flooded with dry ice, such as the graveyards and imposing castles of Karloff’s Frankenstein and Schreck’s Nosferatu, towards recognisably everyday locations: a nondescript Pennsylvania cemetery as evening draws on, and a lonely farmhouse.

The original script itself would be an excellent basis for a stage production, unchanged. Like many of the best horror films – Evil Dead, Halloween, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre – it follows Socratic laws which dictate that the best scripts track a small group of main characters in a single location, and trace the events of a single 24-hour period, lending itself to the demands of a stage performance.

However, this adaptation comes with a twist. Paradoxically, it confounds viewer expectations by conforming precisely to the original film.

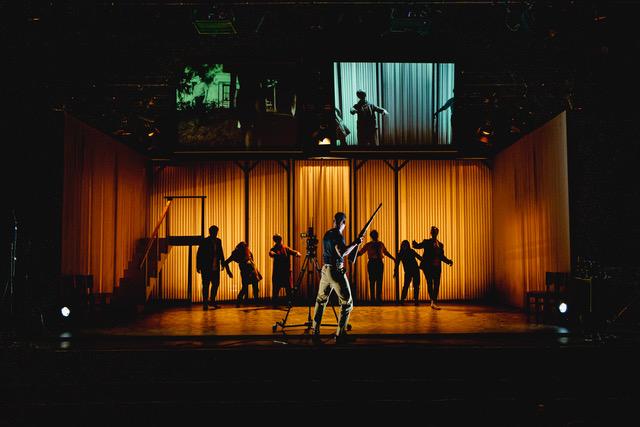

As the performers take to the stage, Romero’s film is projected behind them. Beside that projection is a live feed from several onstage cameras, and the actors reproduce the film line for line, shot for shot, in real time as the original plays behind them.

The live mirroring of the original film adds the potential for elements of comedy at times, which neatly complement what, even in 1968, was a very melodramatic screenplay. The title itself feels so hackneyed and baldly descriptive that it is hard to believe this was the first time a film by that name had been released, though it was far from the last.

“We wanted to be very faithful to the film: to not change it, not romanticise it. It’s funny at times now. Its representation of women is, you know… problematic. But we thought, we’ll present it as it is, in all its flaws and all its glories, and see how we negotiate it, really, through this rule that we set ourselves, that we’ll show the movie in real time, and at the same time, we’ll remake it shot-for-shot, as it plays.

“In a way, you’re remaking the spirit of the film. I know it sounds a bit romantic but when I saw it last in Dundee, I thought “Oh my God, it’s kind of like we’re breathing life into this movie.” Some of the actors are now dead, you know. Some of them are quite old. It felt like we were resurrecting it, really, in an interesting way.”

Romero’s film has a famously whirlwind opening. A pair of siblings, Johnny and Barbara, place flowers on their father’s grave, and Johnny teases his sister that a nearby gentleman might be a ghoul raised from the dead: when his joke turns out to be an accurate appraisal, he tries to save his sister, assuming his place as the hero of the film, only to be killed by the monster, all in the first five minutes.

Imitating the Dog similarly immerse the audience without wasting any time. Their production begins with a group of cast members and camera operators clustered around a table at centre stage, where Johnny and Barbara use toy cars on sticks against A4 backdrops propped up on a table to recreate the opening shots of the film.

The constant shifts between different perspectives, models, areas of the stage, and even actors create unexpectedly comedic moments. Depending on the scene in the film, there can be many Barbaras, Johnnys and ghouls on stage at any moment, running on the spot, peering around cricket bats that simulate the corners of a house, or being represented by miniature figures in a model set offstage.

The results of this can be quite jarring. At once, an audience member can see the carefully edited original film, beneath it, a series of incredibly energetic and minutely choreographed stage performances, and beside it, the breathtakingly accurate product of those performances.

After our apparent hero Johnny is felled is the opening scene, a new one soon emerges to fill the void. Ben is practical, level-headed, and seeks consensus rather than division, but beyond that, he bends the tropes of the horror hero significantly for 1968.

Firstly, he is African American, which says more about Romero’s casting than about this film in particular: many of his films featured black leading actors at a time when there was still widespread prejudice in the film industry. Secondly, he is so focussed on the nightmare scenario unfolding around him, that he can find no time at all to develop a romantic interest in the catatonic Barbara.

The film manages to be at once suspenseful and occasionally terrifying, despite cheap special effects and a mixture of professional and amateur actors, but the film’s capacity for terror is balanced by a satirical edge common to much of Romero’s filmography.

In one iconic horror movie moment, after the ragtag team of desperate and exhausted survivors have zombie-proofed the house, they immediately wheel out the TV, and flick on the evening news.

A talking head confirms what the occupants of the house already know all too well, and declares that “it’s hard for us here to believe what we’re reporting to you, but it does seem to be a fact.”

The news transitions in no time at all from this disbelieving news anchor to Police Chief McClellan. This chillingly calm sheriff is nursing a coffee and organising a huge posse of officers, whose ranks are bolstered by a militia of farmers and rifle enthusiasts.

The facts of the matter are as plain as day to these men, who nonchalantly utter phrases like: “They’re dead, they’re all messed up… if you got a gun, shoot ‘em in the head, that’s a sure way to kill ‘em.”

I ask Andrew if this “shoot ‘em in the head” mentality still characterises the United States of the present day.

“It’s hard not to think that, especially with the way they’re reacting at the moment, because there’s a kind of very simplistic, bullish reaction to the present crisis. And of course, what you know in hindsight is, in the original movie, it seems that although our hero is killed, some sort of collective continuity is maintained. It seems like the sheriff’s posse have won, but if you go to the next movie, Dawn of the Dead, you realise that they haven’t. That “oh yeah, we can deal with it, oh yeah, we can knock it on the head, it’s quite easy”: ‘They’re dead, they’re all messed up’, the sheriff says.

“Actually, the sheer volume of the dead, the sheer weight of the numbers overwhelm the living, and you get part two, which is a classic movie that Romero makes ten years later, set in a shopping mall.

“That sheriff… The brutality, the simplicity… “Force is gonna work.” Rather than trying to work it out in a different way, that still feels quite horribly relevant today, as we sort through this present problem.”

Once the eponymous night is over, Ben is the sole survivor of the terrible onslaught of ghouls, and emerges from the cellar of the country house to be rescued at dawn. Seeing him through a window from afar, a militiaman immediately shoots Ben in the head.

“Good shot,” says Sheriff McClellan. As the credits roll, the militia move on to the next house, and our brave hero is dragged out on a butcher’s meat hook, and burned. In its societal critique and satirical qualities, Night of the Living dead was more thoroughgoing than any other horror film had ever been, and the political symbolism of the film is something that Andrew and Imitating the Dog were keen to emphasise in their production.

“I think there’s two things that I can immediately think of. One is the presentation of the end of an idealised version of America, as we put in the programme notes, the tearing apart of the “white picket fence” version of America. It was something that we thought was good to return to in the Trump era.

“The other thing that we were really interested in was obviously the race politics, that the original makers say was completely accidental, but it felt coincidental, anyway, that in 1968, the year the movie came out, obviously Martin Luther King was assassinated, and Robert Kennedy was assassinated. In ’65, Malcolm X was assassinated. They don’t reference that in the movie, but all that was bubbling up underneath in the way it was made.

“That’s why we put quite a bit of that historical context in. We just tried to layer it in a little bit, in the moments of the film – which in the film work really well – which onstage feel like too-long pauses, really. When he’s boarding up the house, for example, we felt that was a moment where we could bring this historical filtering of what was happening the same year the movie came out.”

Finally, I asked Andrew how he and Imitating the Dog have been coping since the theatres were closed.

“I remember, in December, or maybe early January – and being a hypochondriac geek – reading about the Chinese situation, saying to Pete, the other director, “oh God, this looks crazy. What happens if this comes over here?” That was during our rehearsals.

“I remember buying tubes of hand sanitiser. “Just in case,” I said. He laughed at me, and said I was being an idiot. I’ve still got those bottles of sanitiser, from January the 3rd or 4th, before we started rehearsals in Leeds again.

“We’re trying to think of other projects that might work. We’ve been talking about one at the moment which may get online if we can stream it live, like a live performance, around isolation and dreaming, alternative realities. A lot of our shows have been about that, so it feels like a theme we can follow through.

“The government are furloughing salaries, which means that they’ll pay 80% of salaries for businesses that can’t operate, but weirdly, we found out that they’re not furloughing any businesses that already get government funding: which includes theatres. So, one minute we thought, at least we can stave off our operating costs, which are our salaries, because the government is in effect subsidising them. But they’ve taken that off the table.

“The Arts Council, as far as I know, are fighting back. Irony of Ironies, those of us in the company that were on salaries felt really quite good, and obviously really quite worried for the people that worked for us freelance. We were thinking of ways of cross-subsidising our salaries to them. We could share out the costs of our income, but now the people on freelance now look to be in a slightly better position. Individually, it’s difficult to know how people are going to cope, but we’re trying our best to support what we call the ITD (Imitating the Dog) family, the family of artists that regularly work with us.

“But, we’re all well. At this stage, that’s all you want. You want your family and you want your friends and your neighbours to be well, and safe, and to think about the future.

Again, it comes back to that movie. That film is kind of saying in 1968, amid all that optimism, and all that hope around the Kennedys and civil rights, we’ve still got a long, long way to go.”

If you find yourself bored in week three of self-isolation, you could do much worse than to check in with Imitating the Dog’s brilliant production of this late ‘60s classic, and in the meantime, hope that troupe still remember their lines, let alone their complicated prompt books, for when the theatres do eventually re-open.

All images courtesy of Ed Wareing, with thanks.