Roy Alexander Weise’s take on the Tennessee Williams classic is a vivid interrogation of truth and mortality where the director’s own complex relationship with the play is front and centre.

Maggie (Ntombizodwa Ndlovu) steps into The Royal Exchange’s round. Rihanna echoes through the Great Hall. And a record of R&B hits thrust the audience into 21st-century Mississippi Delta.

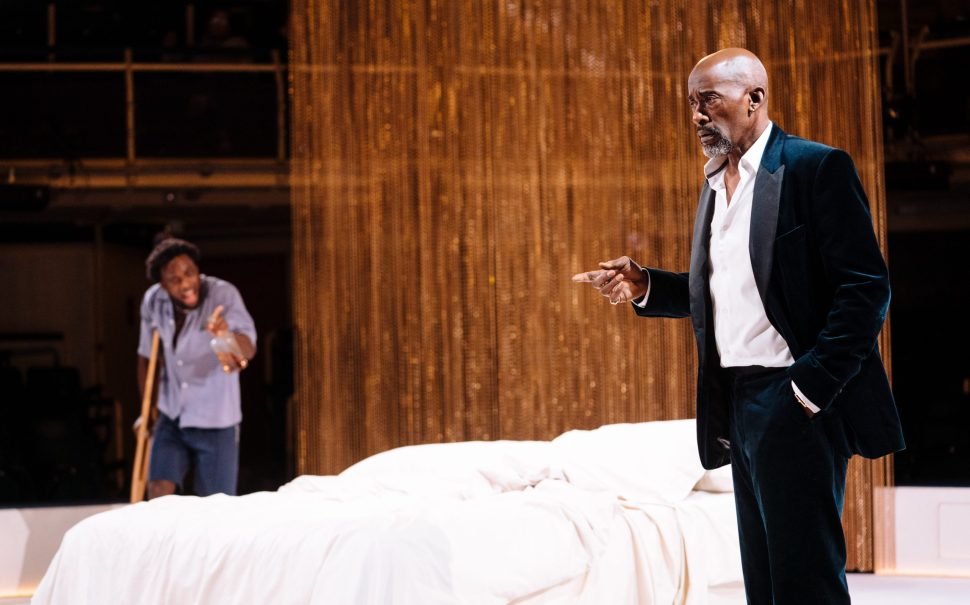

The play follows Williams’ traditional narrative where the Pollitt family are intertwined in a network of ‘mendacity’. The alcoholic Brick (Bayo Gbadamosi) grapples with his love for his wife Maggie while Big Daddy (Patrick Robinson) meanders to his tragic end, unaware of his crippling cancer.

The predominantly black cast uniquely inhabit the stage as new capitalist plantation owners. It is unconventional, conflicting and even more chaotic. The constant battle over Big Daddy’s will within the family is as relevant today as it was in the 1950s.

This has been done before. The Novella Theatre’s cast of 2009 also depicted a black Pollitt family, but they remained within the Deep South of the 1950s. This time, Weise clashes contemporary issues in a contemporary setting.

In an attempt to question where capitalism has led this generation, Big Daddy is a hyper-masculine plantation owner – a complete dichotomy where lines take on a whole new disturbing meaning.

The husky voice of Big Daddy is exacerbated by his evidently modern vape, but the mood of the Deep South pervades costume and language – a struggle as the play enters a new era.

The revolving stage is a picture of consumption. It is littered with whiskey bottles, toy cars, underwear and a hairbrush. The items are scattered around Brick and Maggie’s bed in the dense Pollitt household where privacy is a rarity.

Designer Milla Clarke creates a stunning framework for the action. Williams’ vivid staging is brought to life in the round. The stage is often sweltering – a hazy concoction of yellow light consumes the characters with lies whilst the occasional cold hard blue exposes the tragic truth and Big Daddy’s end.

In moments of relief, Big Mama (Jacqui Dubois) is a joy. She exploits humour in those classic lines at just the right moment. Though in true Williams fashion, there is a distinct uneasiness with the treatment of women, heightened by this modern setting.

In Weise’s dense re-imagination, some of the high drama gets lost. The director described how he is typically ‘allergic’ to the classics and this personal strife unsettles the play, moving it further and further away from realism.

It’s bold and it’s difficult and Weise should be admired for transforming this play, but some of the tragic elements of family struggle become obscured.

Williams’ plays have a large history in this theatre where tragedy hits audiences right in the face at every turn. Among the politics and the humour that Weise finds, the climaxes are distant as the audience engages deeply with the multiplicity of issues he explores.

It’s confusing, and some of the pinnacle moments fizzle. At points, it’s as messy as the room at the play’s opening – though perhaps this is exactly what the performance should achieve.

In more than three hours of action, the task of confronting Williams and reclaiming the lexicon of the Deep South is so complex it becomes its own labyrinth.

It’s visually effective but this metamorphosis asks for stamina, patience and constant engagement from the audience.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is on at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester until 29th April. You can book your tickets here.

Image: Helen Murray