The city of Manchester is undergoing a facelift.

The iconic Town Hall and the neighbouring Albert Square are being transformed as part of a £328million project and numerous new developments are popping up across the city.

With every aspect of the modern city having its roots somewhere in the past – from science to politics, the arts to business – there’s more than just one story for the city. Here are 10 iconic Manchester buildings that tell the story of the city…

Shudehill Mill – 1782 (population at the time: ~16,000)

For generations, Manchester was principally defined by one thing. Something that created thousands of jobs, that poured money and people into the city, and spread its name across the globe, from the southern states of the USA to the department stores of Australia. Cotton.

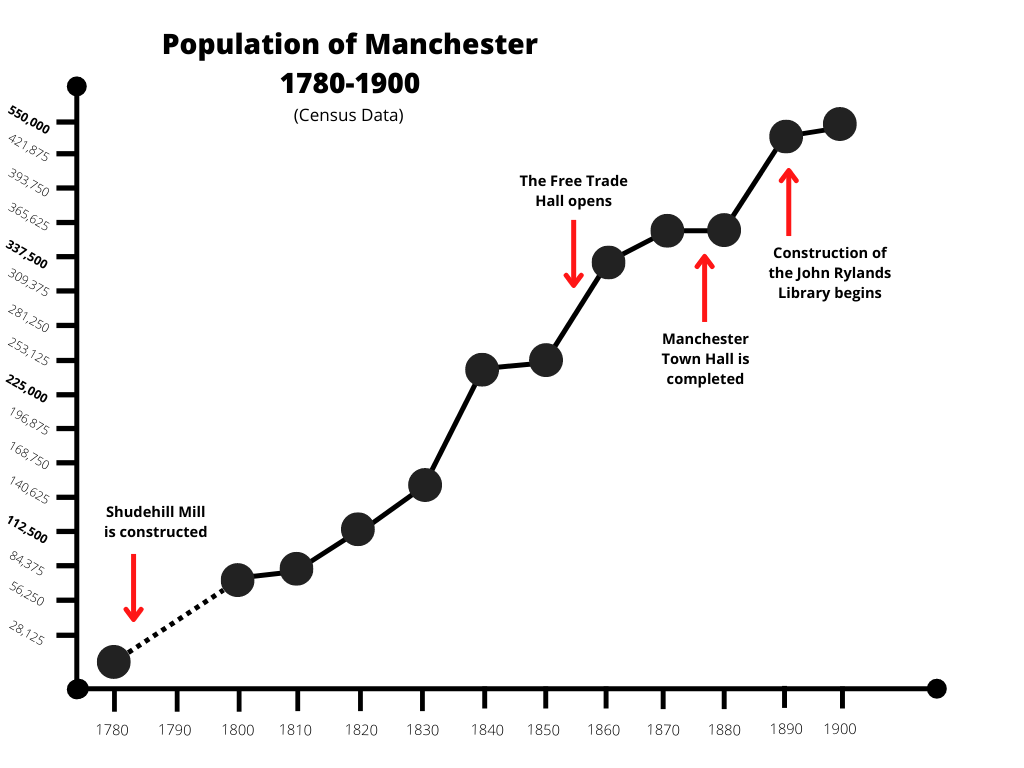

Shudehill Mill is one of the very earliest cotton mills in Manchester, that utilised the latest technology to create an automated spinning machine using a nine-metre diameter water wheel. In its day it was humongous, a five storey building that ran 4,000 spindles. In the late 1700s, cotton represented 16% of the whole of Britain’s exports; a short time later, in the early 1800s, this had grown to 42%. By 1871, 32% of global cotton production was coming from Manchester—now Cottonopolis. And the industry wasn’t the only thing that was growing. In the mid-18th century, Manchester was not much more than a large town of around 16,000 people, by 1801 it had exploded to 75,000—and just 20 years after that it was over 100,000.

The 20th century saw the gradual and then collapse of the cotton industry in Britain; other nations could produce materials locally and at lower costs, and by the 1980s mills were closed as often as once a week. The site of Shudehill Mill lay fallow for years before finally being redeveloped into another of the city’s skyscrapers; once a place of technological and mercantile explosion, it was bombed during the Second World War, when the industry was already in decline, and never reopened.

Free Trade Hall – 1856 (population at the time: 250,000)

The Free Trade Hall could represent so many different aspects of Manchester. Before the hall was even constructed, it was already the site of an infamous Manchester event in the shape of the Peterloo Massacre, where the army killed 17 people and injured up to 600 who were gathered to campaign with the Manchester Patriotic Union for the right to vote and in response to the artificially high bread prices imposed by the Corn Laws.

The Free Trade Hall itself was built less than 50 years later, and was to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws that had sparked the movement. And its political relevance never left it. As a premiere venue in the city for public meetings it saw both cultural icons such as Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, as well as major political figures such as Benjamin Disraeli and Winston Churchill.

Most famously, in 1905 Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney, two Women’s Social and Political Union activists, were forcibly ejected after the speaker, Liberal Politician Sir Edward Grey, refused to respond to their questions on votes for women. The two immediately began a meeting outside and were shortly arrested—this moment is seen as the beginning of the militant aspect of the campaign for Women’s Suffrage.

Manchester Town Hall – 1877 (population at the time: 351,700)

By the late 18th century, Manchester had proved its mettle as a city. It was no longer just a small town but instead a metropolis with incredible ingenuity in both industry and politics. Now with a population 20 times larger than it had been less than a hundred years prior, Manchester needed a home for its local government that matched its stature in the country.

The hall was commissioned in 1863 by the Manchester Corporation who said it should be “equal if not superior, to any similar building in the country at any cost which may be reasonably required”. They knew that Manchester had become a national symbol, and they needed a town hall to match.

It cost up to £1,000,000 in 1877 (with inflation that’s £98,270,000 in 2022) and took nine years and 14 million bricks to build. Inside, Ford Madox Brown’s Manchester Mural depicts the city’s history, and busts of prominent Mancunians, John Dalton and James Pescott Joule among others, were placed.

The Town Hall has always been utilised as a symbol of Manchester and its offerings, even being used for Manchester’s bid for the 1996 Olympics.

Since 2018 the Town Hall has been undergoing significant refurbishments, and is set to reopen in 2024, so its neo-gothic spires and crenelations are hidden from view by scaffolding and tarpaulin. But when the time comes, it will once again epitomise the heart of Manchester.

John Rylands Library – 1890 (population at the time: 505,343)

By the late 19th century, Manchester was no longer the small town it had once been, neither in size nor outlook. The cotton industry had a grip on Manchester, dominating its skyline, its streets, and its canals. And for the select few at the very top of the pile, Manchester was bringing previously unimaginable riches.

John Rylands was Manchester’s first multi-millionaire, a Lancashire-born man who built up his company to a height of 15,000 workers, 17 mills and factories, producing 35 tons of cloth a day, and when he died in 1888 his wife Enriqueta inherited his 2.5 million pound (£305 million in 2020) fortune.

Later in life, John Rylands had begun using some of his wealth to benefit the city that he had gained so much from. Enriqueta kicked that into high gear.

She decided to build a neo-gothic colossus in the centre of the city, built from a pink sandstone that was almost instantly turned black by the coal dust from the mills; a library to rival the ancient ones of Oxford and Cambridge, and, importantly, open for anyone to come and use.

Immediately, the Ryland’s made headlines as it acquired vast collections of rare and valuable books and brought them north to Manchester. Something John Hodgson, Associate Director: Curatorial Practices, says caused great debate:

“When Enriqueta was buying these outstanding collections of rare books, that caused quite a sensation, there were comments in the London press about ‘Why are these collections coming to Manchester?’ Where the people just won’t appreciate these treasures, they’re heathens, basically, uncouth Northerners.”

But that’s precisely why the Rylands had to be built, and the books had to be brought there—to shake off this reputation Manchester had gained as a city of only dumb industrial might.

John explained: “The Rylands is part of a wider endeavour in Manchester to fashion itself as the cultural capital of the north of England in the second half of the 19th century. It wanted to shrug off its reputation of being that shock city of the industrial revolution and to acquire the cultural institutions like the Rylands, the Halle orchestra, the art gallery, and so forth.

It opened to the public on the first day of the 20th century, an icon of the intellectual capacity of the city, and a step forward to prove what it could do.

Sackville Street Building – 1902 (population at the time: 543,742)

The 20th century brought scientific discoveries and developments the likes of which were unfathomable just a short time before—and Manchester wasn’t going to be left behind.

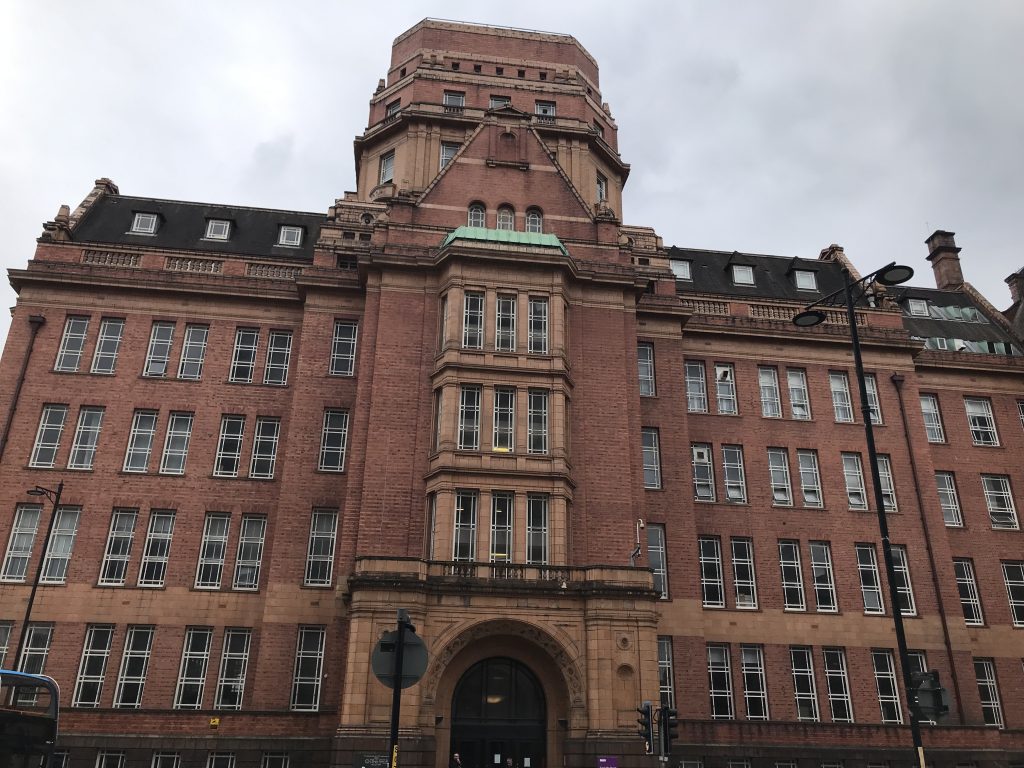

The Sackville Street Building was the bespoke home of the Manchester Municipal Technical School, later the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, when it opened in 1902.

With state of the art lecture halls and science labs, the building drew the eye with its startling looks, and drew minds with its academics.

The likes of Britain’s first female neurosurgeon, Carys Bannister, and World War 2 codebreaker, mathematician, and father of the modern computer, Alan Turing, were just some of the minds who passed through these doors.

The Sackville Street Building stands as a further indication that Manchester was not interested in resting on its proven power during the Industrial Era, but instead was ever-pushing onwards into the future.

Manchester Central Library – 1934 (population at the time: 766,311)

The John Rylands is not the only impressive library that Manchester possesses. The Central Library, when it was opened on the 17th of July, 1934, was the largest public library that was provided by a public authority in the whole country.

As King George V said: “the Corporation have ensured for the inhabitants of the city magnificent opportunities for further education and the pleasant use of leisure.”

Manchester Central Library was not only the largest library of its kind, but it was immensely popular too; not only as a place of study, learning, and relaxed reading, but also because of its unique style.

It was said that between the first stone being laid in 1930 and its opening four years later, the people of the city were curious about what the final building would look like. Its rotunda shape reminiscent of Ancient Rome was unlike anything Mancunians were used to.

In 1968, it was estimated that there were over a million volumes in the library; 2,000 reading places; and 10,000 visitors a day.

Just off St Peters Square, the Central Library is impossible to miss and symbolises the dedication to learning and public good that is fundamental to the city.

Granada Television Studios – 1962 (population at the time: 2,424,000)

Manchester not only was a place of technological and scientific innovation, but it had also become of great cultural significance to the UK.

With authors like Elizabeth Gaskell in the 19th Century and Anthony Burgess in the 20th, the Halle Orchestra founded in 1858 and the many other musicians from the city, and artists like L.S. Lowry, Manchester was the ideal place for the latest cultural development in the middle of the 20th century—television.

Granada was originally a cinema chain that began to move into television in the 1950s, and its founder Sidney Bernstein knew that the north of England, and particularly Manchester, held an ‘X’ factor that he wanted his new channel to harness.

He said: “The North is a closely knit, indigenous, industrial society; a homogeneous cultural group with a good record for music, theatre, literature and newspapers, not found elsewhere in this island.”

Its headquarters on Quay Street was also the site of many of its studios that created its most famous series, including Coronation Street, University Challenge, and Countdown, and, in its first year it broadcast the first ever television performance of The Beatles.

Although most TV production has moved over to the MediaCityUK space in Salford Quays, some of the studios are still used.

Arndale Centre – 1975-1996 (population at the time: 2,370,000-2,316,000)

Covering just under 1.4 million square feet, the Manchester Arndale is Europe’s third largest city-centre shopping mall, serving 41 million visitors annually.

The Arndale has a complicated legacy, being cited as a monument to everything wrong with commercialism and described as a “brutal obliteration” of the city centre.

In fact, on opening day in 1975 the Mayor of Manchester said: “I didn’t think it would look like that when I saw the balsa wood models.” It was seen as ugly, too big, and too modern. On top of that, just five years after it opened, renovation work began, and it has since been redeveloped another three times at great cost.

But this isn’t a list of Manchester’s best loved buildings, but instead historically significant ones, and the Arndale is certainly significant.

The Arndale, and this era, also represents a period of stagnation for the city. Arndale centres were built across the country, a seemingly direct-contradiction to Manchester’s uniqueness. And between 1975 and 1996 is the only time that the population of the city decreased.

By 1975, most if not all of the mills were long gone, Manchester had changed completely and now was a modern city. The Arndale might represent the rise of hegemony that comes with commercialism, and how, for a brief period at least, Manchester somewhat lost its way.

Of course, the Arndale was also the site of the famous 1996 IRA bombing, where a van packed with 1,500 kilograms of explosive were detonated, causing 700 million pounds in damage.

Ironically, it has been said that this catalysed investment in the city, bringing money in to redevelop the site and spurring economic growth. Of course, it also allowed for an Arndale redesign which, hopefully, people find more appealing.

Beetham Tower – 2006 (population at the time: 2,455,000)

As we enter the 21st century, it’s time for some of Manchester’s most recent notable additions to the skyline.

The Beetham Tower was completed in 2006, and was the tallest building in Manchester and the UK’s tallest building outside of London.

It’s an architectural marvel, as it’s one of the thinnest skyscrapers in the world, with a height to width ratio of 10:1.

Not only does it stretch high above the rest of Manchester, it also makes its presence known on windy days when the blade that reaches beyond the top floor emits a spooky hum (the note is a B below Middle C if you were wondering) that can be heard up to 300 metres away.

Beetham Tower is probably one of the most recognisable projects of the modern regeneration of Manchester, built beside a redundant section of the railway viaduct.

The sheet of glass stretching upwards is a stark contrast from the red and blackened bricks that had been so ubiquitous with Manchester for so many years, but it’s a sign of how far Manchester has come, and how it still has much to give.

Deansgate Square – 2018 (population at the time: 2,690,000)

And now, the most recent addition to Manchester’s skyline, the Deansgate Square development.

This cluster of four towers was in development since the early 2000s but was only fully completed in 2020.

The tallest of the four towers, the South Tower, was 30 metres higher than the previous entry on our list, the Beetham Tower.

But I know what you’re thinking. ‘So what? Another set of towers?’

While yes, Deansgate Square is bigger and more ambitious than anything in recent Manchester history, it’s inclusion on our list is more to do with what is yet to come.

As of January last year, additional towers are being constructed nearby, as part of the Great Jackson Street Development Framework.

This speaks to the unresting dynamo that exists within Manchester, even today, that the city is constantly changing, building, demolishing, and rebuilding and is truly a city of the moment.

There are many histories of Manchester, but a throughline throughout all of them is the constant striving for something new.

Already there are ambitious projects underway that won’t be completed for many years, and those that haven’t even started yet, which will change the face of the city forever.

Whether that be office buildings and commercial spaces, hotels and apartment blocks, or the current development ‘The Factory’ which will be home to the Manchester International Festival that broke ground in 2019.

Needless to say, this continues the tradition of Manchester for using the gains of the old to chase the new.