Take a walk around Manchester – a thriving city centre with gleaming high rises, and it’s easy to become lost in the present.

But hidden behind the regular day to day hustle and bustle, there’s a treasure trove of history providing us with echoes of the past.

This month, the Glade of Light memorial was unveiled, honouring the 22 people who lost their lives during the terrorist attack on the Manchester Arena five years ago.

This may be poignant for many of us, happening in our lifetimes.

But what clues are there around the city centre which tell us about the sort of Manchester previous generations lived in?

With the expertise of Chris Nelson, from Manchester’s History Society, join me on a tour as we visit 12 sites which have shaped the city we know and love today.

- Roman Fort, Castlefield

We’ll start with what is widely regarded as the birthplace of Manchester.

It all started in 43AD, when the fate of Britain changed forever. The emperor Claudius succeeded where Julias Caesar had twice fell short, overseeing a complete military invasion of the British Isles.

After landing off the coast of Kent 36 years earlier, it took the Romans until 79AD to establish this Manchester fort, incidentally the same year that Pompeii burned in volcanic ash.

They named it Mamucium, and it became an important base, protecting the route from Chester to York, two major Roman fortresses. Around 500 men were stationed here in its day and it’s become the sight of numerous archaeological projects, uncovering approximately 10,000 artefacts.

Chris Nelson, from Manchester’s History Society explained: “The route to Chester in particular would have marked one of the main thoroughfares in the first century. Although it would have been mostly converts rather than Roman citizens who constructed it, the fortress protected it; nobody would dare to try to trespass here.”

After being levelled off for the industrial revolution, the walls have been reconstructed and now in 1982 formed the UK’s first protected urban heritage park.

From roads to plumbing, Christianity and many latin words we still use today in the English language, the legacy of the romans is impossible to ignore all around us.

2. Liverpool Road Station (Now Science and Industry Museum):

It might be a museum now, but in 1830, this site was alive with the clatter and roar of steam-powered locomotives.

It was here, at Liverpool Road Station that the railway age took off. Pioneered by the engineer George Stephenson, the first inter-city train line in the world ran from the cotton- rich capital of manufacturing Manchester, to the major trading port where it was exported; Liverpool.

Faced with a choice between 12 hour canal journeys, or horse and cart- dominated roads, the railway became a viable alternative for transporting goods.

After the success of the Liverpool-Manchester line, significant investment led to the creation of a national network of lines.

And it wasn’t just industrial cities who benefitted from being able to get around – coastal towns thrived as holidaymakers flocked to their shores.

Liverpool Road Station became a freight station after passenger services were moved to Manchester’s Victoria Station in 1844.

Part of the site was used for the production of Coronation Street after being sold to Granada Television in the 1970’s.

Now a grade I listed building, it survives as part of the Science and Industry Museum.

This isn’t the only invention we have to thank pioneers of the 19th century for…

3. Queen Victoria Postbox Manchester

Whilst there are more than 115,000 post boxes in the UK, around 60% display the letters ER, being built during the reign of our current monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. The R is for ‘Regina’ or Queen in latin.

However, approximately 6% survive from the tenure of Queen Victoria, who reigned from 1837 to 1901.

This post box dates from 1887, and you can spot the ‘VR’ engraved on the front of it to mark the Victorian monarchy.

The Victorians were very much the architects of the postal system we’re accustomed to today. Before them, the postal system was unreliable and recipients had to pay to receive a letter.

It was them who brought in the first adhesive stamp, known as the Penny Black in 1840.

This stamp featured an image of Queen Victoria herself, and costing just a penny, it meant that sending items were now affordable for all.

In the decade following the introduction of the penny stamps, 350 letters were posted annually.

4. Alport Lodge, St. John’s Street

Sound the alarm! Step back to 1642 and the sound of church bells ringing in on this street corner would be a signal for battle in the English civil war.

The two factions fighting were the royalists; loyal to King Charles I, and the parliamentarians; who wanted England to become a republic.

Trouble had been brewing since Charles had become King in 1625. Propelled by his belief that he had a divine right to rule from God, he dissolved parliament for over a decade, until he needed to bring them back to raise taxes for a war with Scotland.

Manchester History Society’s Chris Nelson points out: “This is known to historians as the short parliament. Charles’s army had been defeated by the scots near Newcastle and they were refusing to leave, so Charles recalled them for just three weeks then did away with them again!”

Nelson continues: “It was a double whammy disaster for Charles. They wouldn’t agree to the money, so he fought the war anyway and lost. Then he had the humiliation of having to bring them back and listen to their grievances.”

Parliament had drawn up 204 points they were unhappy about, known as ‘The Grand Remonstrance’, but Charles not only ignored this, but in January 1642, he arrested five MP’s he thought were the ringleaders.

This sparked an all-out war as supporters of parliament (known as the roundheads) and of the King (nicknamed cavaliers) raised their armies and went into battle.

The cavaliers had at Alport Lodge, the site where the plaque is on St John’s street now. When the roundheads descended on Manchester on 26th September, they refused to surrender, and legend has it that they fired their cannon as a warning to parliament’s men as they approached.

The English Civil War was only part 1 of Charles’s downfall, as after losing to the parliamentarians, he tried to ally himself with the scots – his former enemies.

However, after a decisive second defeat in 1648, Charles was put on trial for treason and beheaded the following year.

With all that drama, it’s surreal to think that this quiet street was a part of it during that autumn day.

Next we’re visiting another site which has also seen its fair share of battle cries…

5. Free Trade Hall

To celebrate the successful repeal of the controversial Corn Laws, the symbolic Free Trade Hall was completed in 1856. The building you see today is now The Edwardian Hotel, built a third on the original site.

Benjamin Disraeli, a protectionist turned free trade supporter the Corn Laws, took to the stage to offer his memorable ‘One Nation’ speech in 1872, two years before he became Prime-Minister.

But there was another rising star who would eventually go onto become our leader who gave one of his most famous speeches in the hall. Winston Churchill, a passionate advocate of free markets, gave an address lasting over 90 minutes here in 1904. The Times described it as ‘the most powerful and brilliant’ talks he gave.

Nelson tells me: “This was the epicentre of free enterprise and thought, a place for the Alan Sugars’ and Richard Bransons’ of their day to congregate and mingle. Everybody who was anybody was in that hall that night as Churchill raised the roof!”

Everyone from Charles Dickens to Bob Dylan has held an audience here, but one of the most colourful days seen by the hall was in 1905.

On 16th October of that year, suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny were arrested for interrupting a Liberal Party meeting. They burst onto the scene and demanded election pledges were made to incorporate votes for women. After being swiftly ejected from the venue, they were both arrested for disruptive behaviour and spat at a police officer on their way out.

It marked a more militant turn in the approach of the suffragettes, including a bomb being detonated in 1913 back at the Hall.

This would one eventually lead to success for the women’s suffrage cause, but it would be an uphill struggle, as we’ll found out later.

6. The Midland Hotel

With its grand opulence beaming from the entrance, you might recognise this hotel as the venue which Boris Johnson gave his speech at the Conservative Party Conference last October.

Designed as a gateway stopover to Manchester for wealthy businessmen entering from Manchester Central Station, this Edwardian building also welcomed Winston Churchill, who gave a speech here in 1904 to the Free Trade League.

But also in that same year, it was the scene which introduced Henry Royce and Charles Rolls back in 1904.

The duo went on to export their iconic luxury brand of Rolls Royce Motors around the world, and in 1915, were commissioned by the Royal Airforce Factory to supply engines for World War I.

Everyone from the Queen Mother to The Beatles stayed here, and in the 1990s, David and Victoria Beckham checked in on their first date here.

It’s even reported that Adolf Hitler stayed here, and was so impressed that he wanted to spare the area around the hotel as he wanted to use it as a base, in the case of a Nazi invasion.

Clearly, endorsements for the building derive from all quarters, however dubious!

7. The Peterloo Massacre

It might be difficult to imagine now, but 200 years ago, St Peter’s Square was a field. A field with a bloody history.

In 1804, the introduction of the Corn Laws restricted the importation of cheap corn from abroad. It had been designed to protect British farmers from being undercut, but had the knock on effect of dramatically increasing prices of bread for the working classes.

By 1819, the mood in Manchester was febrile. And on the morning of the 16th August, a crowd of 60,000 gathered to protest against the hardship they felt.

However, when troops were called in to disperse the crowd, things turned violent. Eleven people died and 140 were injured.

The event got the name of ‘The Peterloo Massacre’ by the Manchester Observer, and was compared to the Battle of Waterloo which had taken place four years earlier.

Three years ago, in 2019, Manchester City Council commissioned this memorial by the artist Jeremy Deller, which has 11 steps, engraved with the names of each of the victims.

As Nelson informs us, this would mark a turning point for change:

“What happened in Peterloo that day certainly wasn’t pretty but it was real people power. It terrified the authorities and galvanised radicals to call for representation and reform, and the right to meet and protest.”

Next we’re heading somewhere which has long been a focal point of social equality…

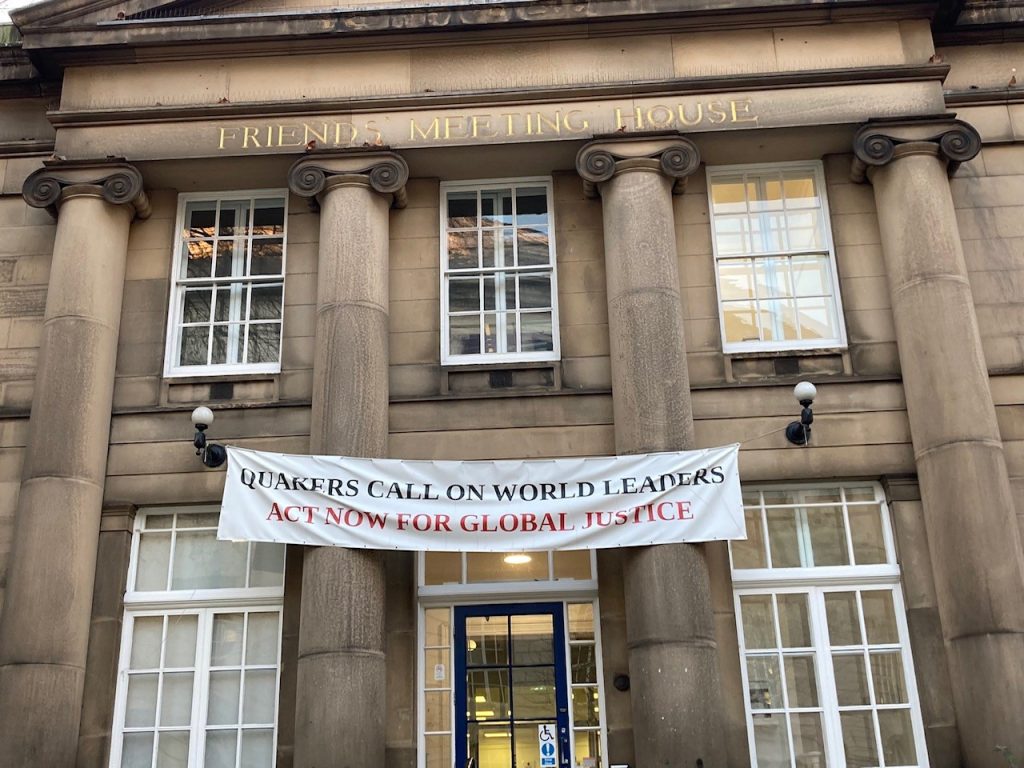

8. Friends meeting house

Whilst this building on Mount Street welcomes friends of all kinds through its doors, the religious society of friends is actually another name given to the Quaker faith.

Built in 1828, the church you see today was funded using donations from local followers of the Quaker religion. Among these was one attendee name you who might have heard of – John Dalton.

Dalton was the chemist who introduced the world to the concept of Atomic theory. Inspiring later geniuses such as Albert Einstein and Marie Curie, the theory that all matter can be subdivided into cell structures has enabled us to live with the medical treatments and vaccines we have today.

The Quakers were no stranger to supporting social causes. Using this meeting house as their base, they backed the abolition of slavery and boycotted products grown on slavery plantations, such as coffee and sugar.

The campaign to abolish slavery found a strong voice in Manchester, as we’ll see with our next site, just around the corner…

9. Abraham Lincoln Statue

Unveiled in 1919, the inception of Abraham Lincoln’s statue celebrated Manchester as an ally to him during the American Civil War.

Lincoln was the president overseeing the victory for the Union over the Confederate States in 1865, with the capture of Richmond, the Confederate capital. He also initiated the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing three million slaves.

Having been at war for the cause for almost all of his presidency, Lincoln was sadly assassinated just five days after the formal victory, inside Ford’s Theatre in Washington.

Manchester had helped Lincoln by boycotting cotton trade with Confederate states who were adopting slave labour.

Lincoln responded by personally penning a letter of thanks to Manchester’s residents.

With America progressing from the ashes of war, Manchester would also rise as united through tragedy in 2017.

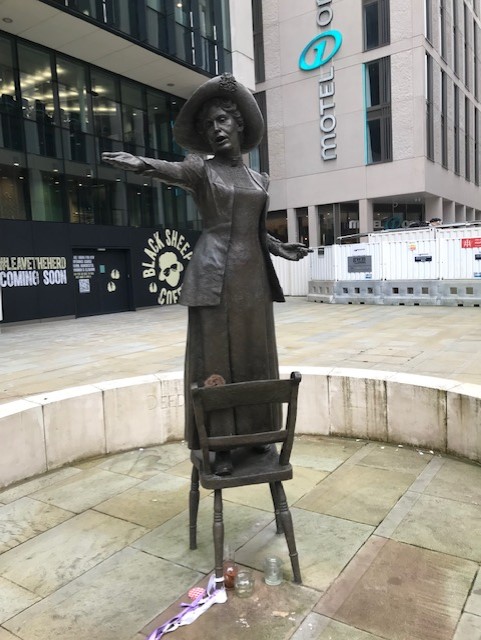

10. Emeline Pankhurst statue

Here stands one of the key architects of twentieth century social historic change, one that would permit women the opportunity to vote.

This statue of Emeline Pankhurst was unveiled in 2018, 100 years after women were granted the right to vote in elections.

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was finally passed. This allowed married women over 30 who lived in a property charging at least £5 per year, or university graduates, the right to vote.

It wasn’t until 1928, that all women were afforded truly equal voting rights as men, after the passing of the Equal Franchise Act.

However, Emeline wouldn’t live to see this second milestone, as she tragically died two weeks before it became law.

It had been a long and hard fought battle for equality. Together with her daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela, the Women’s Social and Political Union, or as we know today, the suffragettes.

Frustrated with the slow progress, the new group would adopt the motto ‘Deeds not words’ and set about disrupting political speeches, property damage and hunger strikes in prison. Whilst Emeline was imprisoned three times, it was Emily Davidson, an ally of Emeline’s, who perhaps took part in the most shocking act of all. In 1913, she fatally threw herself in front of the King’s horse at The Derby.

However, in spite of all these fierce tactics, it is debated by historians as to whether it was this, or the contribution of women towards World War I, which eventually secured them the vote. It’s estimated that a million women helped work in munitions factories and the land army from 1914-1918, filling in for men who were away in the forces.

Emeline, who was born in Moss Side in 1858, remained in the city and used her home in Nelson Street as a base for organising suffragette campaigns.

Take a 30 minute walk up Oxford Road on Thursdays and Sundays and you can now visit the family home of the Pankhursts. For now, Emeline invites you to be part of her meeting circle here, as you transport back in time to the early twentieth century.

11. Queen Victoria statue- Picadilly Gardens

Next we move onto Piccadilly Gardens. The land you see around you 300 years ago was a labyrinth of clay pits, dubbed ‘Daub holes’.

In 1755, Lord of the Manor Sir Oswald Mosely donated the land and it became the site of Manchester’s Royal Infirmary, later a Victorian pleasure garden a century later.

But one feature with a presence nobody can ignore here is that of Queen Victoria.

Here, sitting proudly on her throne we see the statue which was constructed to commemorate her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, but wasn’t placed here until her death in 1901.

Spending 64 years on the throne, Victoria is our second longest serving monarch, after the current Queen Elizabeth II, who reaches an incredible 70 years this year.

Empowered by the industrial revolution, Britain extended its enterprise and influence across the world during Victoria’s reign. Gaining access to cheap labour and raw materials, the Victorian Britain offered technical improvements such as railways, new medicines and education. From the jewel in the crown of India to much of Africa, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 only accelerated imperial expansion.

Nelson sums up Britain’s success during the Victorian period: “That old saying that the sun never set on Britain’s empire couldn’t be more true. Queen Victoria went a bit quiet after Albert’s death but the steam engines kept rolling as our empire kept sprawling. Britain was the most powerful nation in the world.”

We have one last site to visit before the sun sets on our tour, and we’ve saved the most important until last.

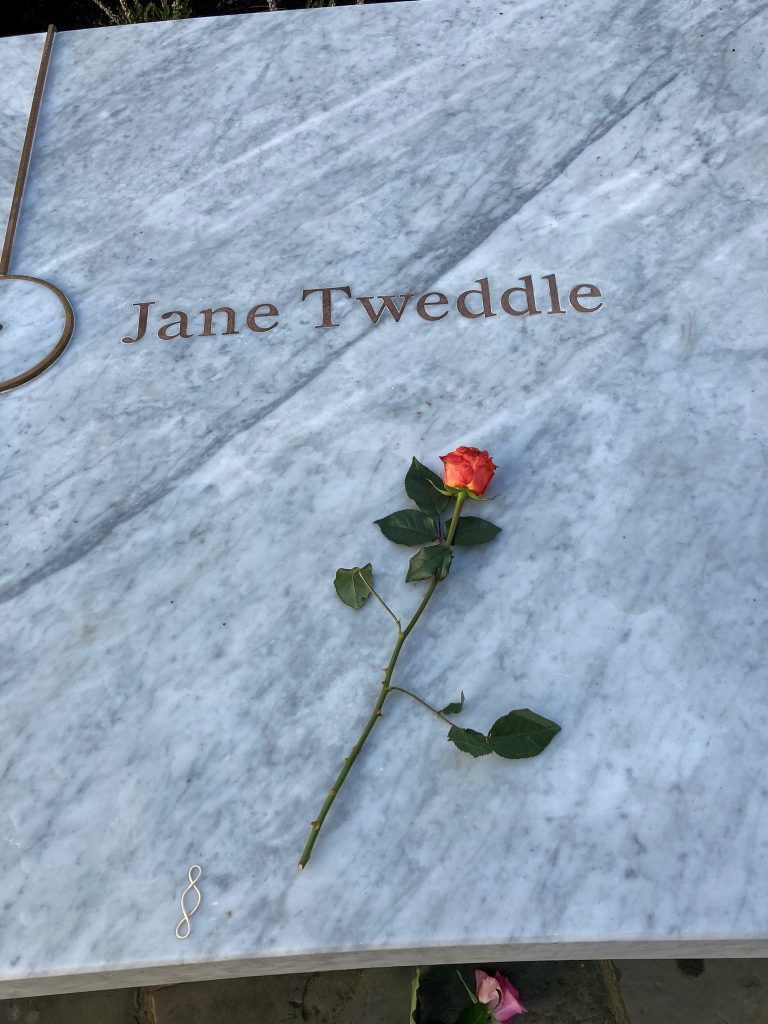

12. Glade of light memorial

Our final tour stop takes us to a site still very sensitive to many living in this city.

The AO Arena as it is now known became a scene of tragedy during an Ariana Grande concert on 22nd May 2017.

Twenty two people lost their lives that night, along with 1,017 suffering injuries, as a bomb was detonated as customers were leaving the venue.

The white marble circle you see here not only lists the names of the 22 victims, but there are memory capsules contained inside, made by their families.

The empathy felt by the city and further afield in response to the attack was one of overpowering unity in the face of adversity. Thousands attended a vigil in Albert Square the following night, and a nationwide minute’s silence was held three days later.

Her majesty the Queen visited the Manchester Children’s Hospital to where she met some of the injured victims and staff looking after them.

Ariana Grande returned to the city two weeks later, where a special concert was organised at Old Trafford Cricket Ground to remember those who died. It was watched by a peak of 14.5 million viewers, the highest for a live event that year and raised £2 million for those affected and bereaved by the attack.

The mother of Martyn Hett, who lost his life during the bombing said: “It is beautiful but I cannot wait until spring and early summer when everything is green. Martyn’s space is under a big old tree and I want to sit underneath it and remember him.”

She added: “It is very heart-warming to see everyone being remembered in a space together.”

So that brings us to the end of our tour. Whether you know someone affected by the attack or remember the devastation five years ago, take a moment to reflect on the solidarity of Manchester as we vow to remember all those affected, as part of our history.