Billed as a future ‘American classic’, Sweat promises big things. While it may be too early to call it a classic, Manchester’s new production is a tensely-wound, warm-hearted portrayal of a community in decline, with tragic consequences.

Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama is set in the slowly deindustrialising Rust Belt town of Reading, Pennsylvania, around the Olstead steel plant. Based on extensive interviews Nottage did in Reading, which the Census Bureau recorded as the poorest city in the US in 2011 – not long after the play’s action ends – this is both social realist drama and sweeping national story.

Directed by Jade Lewis for the Royal Exchange and set amid the backdrop of the 2000 presidential election, this revival is well-timed ahead of another one, with the disaffected community at its core paralleling those that voted Trump in their droves.

Nottage focuses on a community of tight-knit friends and family, helmed by steelwork factory workmates Tracey and Cynthia, who have stuck by each other in thick and thin for more than two decades. But with management looking to cut corners and outsource to cheaper, less troublesome workers, old and new resentments put the characters on a collision course, spiralling them towards an inevitable tragedy.

The action also veers forward eight years, into the aftermath of this tragedy. Two scenes which bookend the play are set in parole meetings, where parole officer Evan (Aaron Cobham) keeps dignified order over his charges.

The first of these introduces us to Jason (Lewis Gribben), a disaffected young white man with Aryan Brotherhood tattoos; the second, his old friend Chris (Abdul Sessay), a thoughtful African-American who is trying to turn his life around.

We then jump back in time, but the unsettling knowledge that something happened to put the two in prison haunts even the light-hearted scenes of the earlier timeline.

You may feel like you know where the play is going, and to a certain extent the writing is on the wall. But even as the strings of Nottage’s tightly-wound drama fray to breaking point, the drama never feels predictable, and there’s a shattering twist that upends the final tragedy.

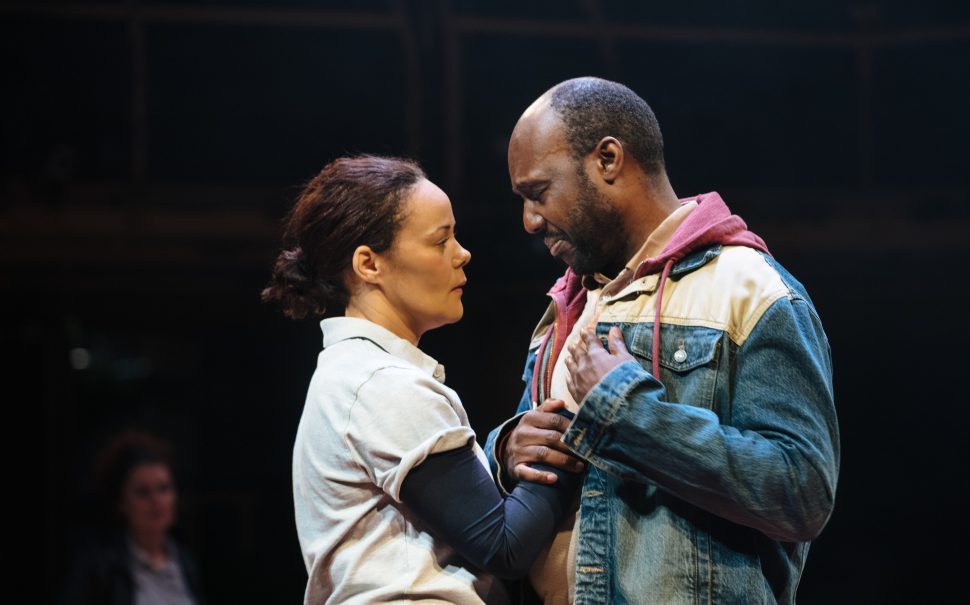

It’s a true ensemble play, with the friendship between Cynthia and Tracey, and peacekeeper Jessie, at its heart. Carla Henry is excellent as the sympathetic but tough Cynthia, a black woman who has spent two decades on the factory floor, while Pooky Quesnel brings a brashness and brittle temper to white, increasingly embittered Tracey.

Colombian bar worker Oscar (Marcello Cruz) is another standout in a quieter but still impactful role, desperate for a better life and increasingly frustrated by the casual racism thrown his way.

When Cynthia is promoted to management at the plant, old relationships – including with Tracey – begin to break down. This is a dark story with a simmering undercurrent of racial and economic tension, but it’s also frequently laugh-out-loud funny. Kate Kennedy’s comedic timing as Jessie was particularly brilliant and the pitching between moments of high drama and comedy was faultless.

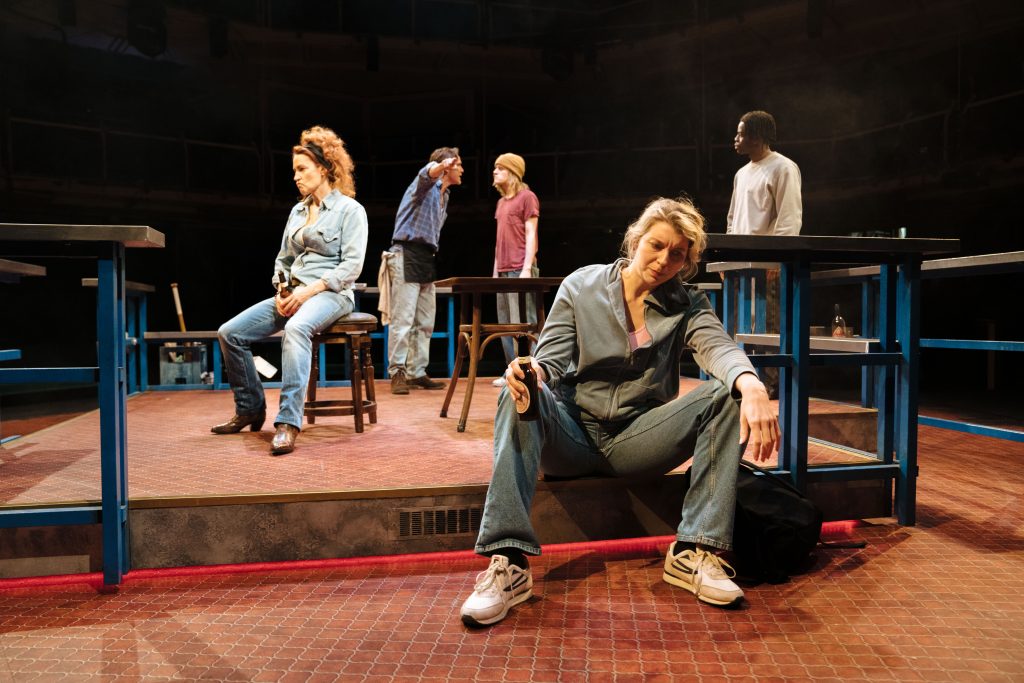

Staged in the round at the Royal Exchange, the set is austere and institutional, with just a dingy brick floor, a few chairs, and a simple surrounding square of bars at different heights that form the outer perimeter of the action. Imposing steel blocks hang from the ceiling, a constant reminder of the machines the characters depend on. The lighting and soundtrack are equally minimal, subtly shifting as the mood darkens, while a spark machine on the ceiling is another clever touch.

Sound designer Elena Peña transitions between most scenes with a medley of news headlines, positioning the Reading community as a pawn in a much larger national story, while a succession of hit noughties tunes lead in the raucous birthday celebrations early in Act 1. The transitions are seamless and ensure the action never lags, while the costuming also feels well-chosen. We rarely see the ambitious and dedicated Cynthia out of her work gear, with her sleek business suits visually clashing with the increasingly shabby other characters.

With no walls and a brutalist space, there are few of the trappings to indicate that we’re in the bar where most of the action happens, which makes the play feel somewhere rootless. The characters’ uneasy movement and interactions make good use of the in-the-round staging, but the stage design feels better suited to the parole scenes, and some dialogue is slightly muffled when the characters turn away.

This is both a state-of-the-nation play and also an intimate drama of relationships within a close community, and part of its power is how resonant it feels more than two decades on and across the Atlantic. The divisive rhetoric about immigrants, the scapegoating, and the disenfranchisement of the working class, all ring uncomfortably true against our own current politics.

There are some flaws: occasionally the dialogue feels unrealistically poetic, especially compared to the snappy, wry tone of the majority of exchanges. Some characters feel slightly one-note – Jason’s restless energy and latent rage keep the audience on edge in his scenes, but mean there’s little room for him to manoeuvre in the heightened moments of tension, and the mother-son relationships feel somewhat underdeveloped.

But this is an ambitious, taut drama that feels pacey and gripping despite its near three-hour run time. Sweat continues at the Royal Exchange until Saturday 25 May.

Images credit: Helen Murray. Images used with permission of the Royal Exchange Theatre.