Ofsted and the government should leave education to the teachers as a ‘climate of fear’ is forcing their finest to quit, claims the Manchester Teacher’s Union chief.

More teachers are quitting the profession than at any point in the last 10 years, according to the latest figures.

It is estimated that around 40% of new teachers quit within five years.

John Morgan, general secretary for the National Union of Teachers (NUT) in Manchester, believes that teachers are being forced out of the profession through ‘intolerable pressure’ by Ofsted.

‘Box ticking’ culture and a huge workload has changed a job that people did ‘genuinely for the love’ into a 60-hour working week that is ‘robotic in nature’, he claimed – adding that teachers were ‘terrified’ of Ofsted.

Mr Morgan said: “There is a real climate of fear in schools. When I joined the profession 20 years ago, there was a very warm atmosphere – more about working together.

“If you had serious issues, problems with a class, a senior leader would come in, give you advice and get you through it. But now, it could be the end of your career. The pressure is intolerable.

“Back off the profession and let the profession make the suggestions about how the education system should be run.

“Every four to five years we get a change in direction, but we went from Michael Gove to Nicky Morgan and the only thing they know about teaching is that they both went to school.”

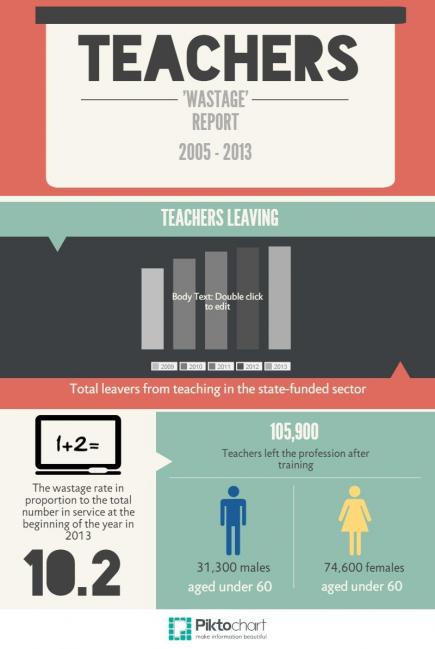

The most recent figures from the Department for Education show that 49,373 qualified teachers quit state-funded schools within a 12-month period leading up to November 2013.

This is the highest number of leavers in 10 years.

The report also shows that more than 100,000 teachers left the profession even after completing their training.

A survey report from the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) indicated that three-quarters of trainee and qualified teachers have already considered leaving the teaching profession.

A total of 76% said that they wanted to leave because their workload is too high.

“Teachers are working up to 60 hours a week,” said Mr Morgan. “It’s turned from a profession where people genuinely go into it for the love of what they do, to almost robotic in nature.

“In some schools, they’re terrified of Ofsted. They’re ticking boxes, and management have seen a teacher that is not quite getting the grade, so to prove to Ofsted that they’re doing the right thing, they put them through a six-week ‘competency’ process.

“They don’t give them any real support. Yet this teacher might be somebody who has worked for 20-30 years in some cases, who has had fantastic results and great rapport with kids.

“It’s often very, very small things that they say the teacher is not doing that don’t make any great difference. But because of the scare of Ofsted, and that’s the real motivator behind all of this, schools are terrified of them coming in.”

Avis Gilmore, regional secretary for the National Union of Teachers in the North West, believes there are two groups of teachers that are being forced out – the new recruits and the older, more experienced members.

The experienced teachers however, in some cases, seem to find the drastic changes more challenging.

“The general view is that because things have changed so much within education, it’s more difficult for people who have been teaching for 20-25 years to adapt. But in some cases they’re not being given the support to adapt,” said Ms Gilmore.

“Quite often the changes involve a lot more bureaucracy and a lot less teaching. It’s quite difficult for teachers who have taught successfully to cut back on what they’re teaching in order to fill in forms to prove that they’re doing it.

“The other reason is that they are more expensive. They’re likely to be teachers that have reached the top of their salary range.

“They’ve got additional salary responsibilities that they’ve taken on, and it’s much cheaper if schools are struggling financially to remove them from their post and employ newly qualified teachers.”

Liam Duffy, RE and history teacher at Loretto High School in Chorlton, 43, who has worked in the profession for 15 years, said: “As a teacher I feel it myself, but I know there are teachers out there who feel it significantly more.

“Usually there’s significant pressure on a head teacher at schools who work to attain results, which is obviously a government-led policy.

“I generally feel like across the board [in the UK], middle management – heads of department and heads of the year – suffer an increasing amount of stress because of the work rate they have to fulfil and the hoops they have to jump through.

“Bureaucracy is quite a prevalent situation where lots of people in government and locally say that they want to decrease it but it seems to have increased.”

Mr Morgan says that teachers are monitored ‘to death’ within schools, citing those with ‘excellent’ track records that hypothetically had one year’s bad results.

But he explained, rather than consider the socio-economic factors for poor results, they ‘point fingers’ at the teacher based on pre-set data.

“We [NUT] campaign against the absolutely mad focus on data now – it’s all that matters,” said Mr Morgan. “Rather than looking holistically at the whole aspect of performance, they look at data agenda and if you don’t meet targets in that data.

“And when Ofsted inspectors come in, they already know more or less what they’re going to say about a school because they’ve looked at the data that is released every year.

“Then they justify various numbers that have been generated. That’s not looking at the wide range of things schools do.”

When quizzed about Ofsted data, Ms Gilmore said: “There are occasions where they [Ofsted inspectors] will say to a head teacher in the school that their teachers are outstanding.

“But they can’t say the school is outstanding because the data they looked at before they even came to the school means you can’t be an outstanding school.

“So not only is there massive pressure, but the outcome before any inspection is pre-judged.”

Ms Gilmore added that socio-economic circumstances are not taken into consideration in Ofsted’s pre-set data which may have otherwise indicated ‘fantastic’ effort in challenging circumstances.

“It’s not based on schools in really deprived areas who actually make a huge difference to the pupils that are there, but because they’re not all getting A*s or A-Cs at GCSE then the school cannot be classed as a successful school,” she said.

“And yet, they pay money towards breakfast clubs, buy spare sets of clothes, wash them, bring them back to the kids – some of these things have got to be done so they can study properly to the best of their ability.

“But there’s no chance in all the data of those sorts of things that schools are doing for the most disadvantaged pupils. That’s the frustration of it all.

“Sometimes no matter how fantastic a job you are doing in really challenging circumstances, Ofsted will still condemn you as a school.”

When looking at a solution, Mr Morgan said: “They say they’re not, but we strongly feel that Ofsted reflect government policy.

“The country in Europe that has allegedly the best education based on the PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] tables is Finland, and they don’t have inspections.

“Schools regulate themselves, so they do self-assessment. Obviously there must be checks and balances to make sure that they’re actually still alive, but they do that themselves and there’s no inspections and teachers aren’t put under this pressure.

“So, there’s an example which is held as a shining beacon of success and yet they don’t do the things that we do.”

Julie Ward MEP, a minister for culture and education, whose sister is a teacher, said: “Teaching is no longer the valued and respected profession that it used to be, or at least that’s what it feels like if you are working at the coal face with more and more pressure to respond to government demands for data, instead of more and more time spent in the classroom.

“Teaching was always a vocation, which meant doing a job because you loved the work. With the shift away from pupil engagement, the profession will find it hard to retain those who feel most passionate.

“Teachers, more than anyone, want their pupils to succeed and for their schools to be recognised as ‘good schools’.

“But when measurements have a narrow focus that favours exam results rather than classroom practice and a pupil-centred holistic approach, it is demoralising for all concerned, and doubly those who operate in deprived areas with more challenging pupils.

“In a global market, Britain can’t be complacent about teacher retention.”

A Department for Education spokesperson told MM: “We all know the difference a great teacher can make to the life of a child.

“And we’re fortunate to have the most highly qualified teaching profession ever, with more graduates from top universities choosing teaching than ever before.

“We want to encourage even more talented people into the profession, to inspire young people to achieve their full potential.

We have launched a new recruitment campaign and want to see a new independent College of Teaching established that will give the profession greater responsibility over standards and development.

“And place teaching on an equal footing with careers like law and medicine, attracting more of the brightest and best.

“The Secretary of State has made clear to the teaching unions our commitment to working with them to help reduce unnecessarily high workloads, caused by needless bureaucracy.

“In October we launched our teacher workload challenge, which received more than 43,800 responses – we will use these to build on the steps we have already taken to tackle workloads.”

Ofsted recently announced that school inspections will now be shorter but more often, as part of their radical reform to education inspection.

Image courtesy of Bill Erickson, with thanks.