Forensic psychologist Kerry Daynes told MM why the police often fail to intervene in stalking cases, and how they can improve safeguarding of vulnerable women. As trustee of a leading authority on stalking – The Suzy Lamplugh Trust – she’s using her trauma to advocate for others.

Her suburban sanctuary was shattered in an instant, two words sprayed across her garden fence: JILL DANDO. After decades as an expert witness to rapists and murderers, Kerry Daynes said that stalking usually escalates to violence. She felt “blindsided” – fearful she’d die at the hands of a stranger. Famously, we still don’t know who killed Dando on her doorstep, and Kerry’s stalker was only issued with a warning for harassment – she reckons “institutional misogyny” in policing hasn’t gone away.

According to the latest ONS data, one in five women has been a victim of stalking and as Daynes is all too aware – having made a living expertly testifying in court- on average a man kills a woman every three days. Officials say violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a “national emergency”.

As of March 2024, around 42% of victims said their stalker had used online methods to threaten or harass them – just like hers did. Sadly, that risk of harm often goes overlooked when it’s not an ex-partner.

She thinks authorities often fail to intervene because women’s safeguarding is neglected in police work – safety measures haven’t been as “proactive”.

A man with “no professional connection, no personal connection” to Daynes, had been relentlessly abusing her online – for months, despite having only seen her on TV. As well as the message on the fence, her cat was found dead.

The torment changed her life. She suffered from so many physical symptoms of stress, because of his threatening behaviour and harassment. Built up anxiety from mentally risk assessing herself every day – she’s now completely deaf, she revealed.

She said she really needed to tell that story – recently she’s taken a step back from the courtroom to focus on advocacy.

“I’ve been able to convert that adversity and that really hideous experience into something that is useful and meaningful.”

Daynes said we have problems with the police responding to stalking effectively. Despite doing her best to make authorities aware of her nightmare, at the time they couldn’t really do much, legally – She said: “They didn’t even know what stalking was until 2012.”

It’s true – Stalking Protection Orders were only passed into law in March 2019, when Daynes went through her ordeal, the CPS had no legal definition to go by, so were unable to prosecute her stalker.

She told MM: “It remains the case that police just don’t have adequate understanding of what stalking is.

“They don’t take it as seriously as they should.

“I think recognising and responding to that risk of harm – it’s something that is an ongoing issue.”

Daynes thinks looking for ways to put the onus on vulnerable women is more common than safeguarding, victim blaming and downplaying risk feels like the norm amongst authority figures.

She said the idea we’re responsible for everything that happens to us is intertwined with all kinds of different stereotypes and “the whole fabric of our society”.

“I understand this desire for us to want to believe that we are safe and that we are somehow in control.

“If you say, well, this woman was doing absolutely nothing wrong, and then a man chose to rape her, then we have to acknowledge that actually – at some point in our lives, we might be totally minding our own business, and somebody is going to choose to offend against us in some way.

“And that is a frightening thought.”

Highlighting media’s impact, she added: “You don’t notice the different things that influence you – it’s woven into our language.

“We talk about however many women got raped this year and we very, very rarely say, X number of men raped women this year.

“We need to start putting the agency where it belongs.

“We can’t fully protect ourselves against being offended, but the more people that maybe change the language – it’s those little things, the more that they drip down into society, [and]the more that we talk to kids, the better life will get.

“It’s just that unfortunately, we’ve also got the Andrew Tates of the world.”

Daynes said police often mistake stalking for harassment from disgruntled exes or people with grudges, but intimate partner violence is not the only factor to consider.

Women are significantly more likely to be abused by someone they know, but feeling disenfranchised and angry without someone to blame, more men are indiscriminately turning to sexism on social media.

Figures suggest the highest number of online harassment and cyberbullying incidents in the UK are in Greater Manchester, accounting for 46.7% of all reports.

The distress caused by stalkers is long lasting, yet most cases are handled without truly acknowledging the gravity of the situation.

“It has such profound psychological impact on victims,” Daynes said.

Areas of Greater Manchester have some of the highest stalking rates in the country, but just 6% of reported cases result in a charge.

Three years ago, The Suzy Lamplugh Trust submitted a super-complaint against the police, on behalf of the National Stalking Consortium, for systemic issues in the response to stalking across England and Wales.

The charity is on a mission to reduce the risk and prevalence of abuse, aggression, and violence through education, campaigning, and support.

Legislation must reflect women’s risk: “The government needs to help police with their understanding,” Daynes said.

At the end of 2023, the Minister for Safeguarding and VAWG, Jess Phillips, and Home Secretary Yvette Cooper announced they were issuing Right to Know rules to crack down on online stalking.

And in April last year, it became easier for police to apply for legal protection for staking victims – previously, the threshold for evidence was a high criminal standard.

But the Home Office has not made misogyny a hate crime, as to do so would be “more harmful than helpful”, according to a 2021 Law Commission report.

As a trustee of the Suzy Lamplugh Trust, Daynes recommends investment into training police officers to recognise stalking – so they can gain understanding of the real psychological impact and potential physical harm it causes, to deal with victims effectively.

She told MM that empathy was “really, really lacking” when she went to police and she’s not alone.

“Time and time again, victims are just not feeling that they’re being taken seriously,” she said.

Her expert suggestion is that a multiagency team should handle cases where a dangerous person has been identified, working with both victim and offender to put protection at the forefront.

Daynes thinks we should be looking at stalkers holistically, as whole people, to effectively minimise risk.

She said police should put particular emphasis on the potential for them to cause harm to another person “and what we need to do about that”.

“There are no monsters here, there are only human beings.” she added.

She stresses the need for rational compassion – understanding why offenders behave the way they do, and the mental health struggles they’re experiencing – which is not the same as empathy.

Violence and aggression usually stems from mistreatment in childhood, but she clarified there’s no simple cause and effect between being a victim and then going on to become an offender.

Daynes described her experience in the late 90s and early 2000s, with former Wakefield prison warden and convicted rapist John Hall, in her collection of anecdotes The Dark Side of the Mind, a Sunday Times Bestseller.

More than 20 years later, things haven’t much changed. Take for instance, the child protection investigation unit “making it worse” for victims; or disgraced former officer from Oldham Dean Dempster and the 98 GMP officers accused of sex offences in 2023.

Lamenting on the “institutional misogyny” within today’s police forces – men seeking to wield authority and abuse their power over women and girls – she added: “It saddens me that we’ve not made the progress in that time that I hoped we would.”

According to her memoirs, self-policing with outdated attitudes has enabled preventable VAWG for years. Rape culture was so commonplace in the past, prolific predators notably avoided jail – things have improved but “there is more to be learned and there’s so much more to be done.” Daynes told MM.

In a blog, she wrote: “I was let down by the police.

“They failed to join the dots and recognise my stalker’s repeated actions as the psychologically harmful, illegal offence they were.”

GMP’s website says approximately a third of all arrests made in the region are for domestic abuse offences, including stalking. So, the force has developed a specialist programme, for the next three years, to ensure it’s equipped to “protect people, change perpetrator behaviours and keep people safe”.

If you’ve been affected by stalking, you can call the National Stalking Helpline for advice at 0808 802 0300.

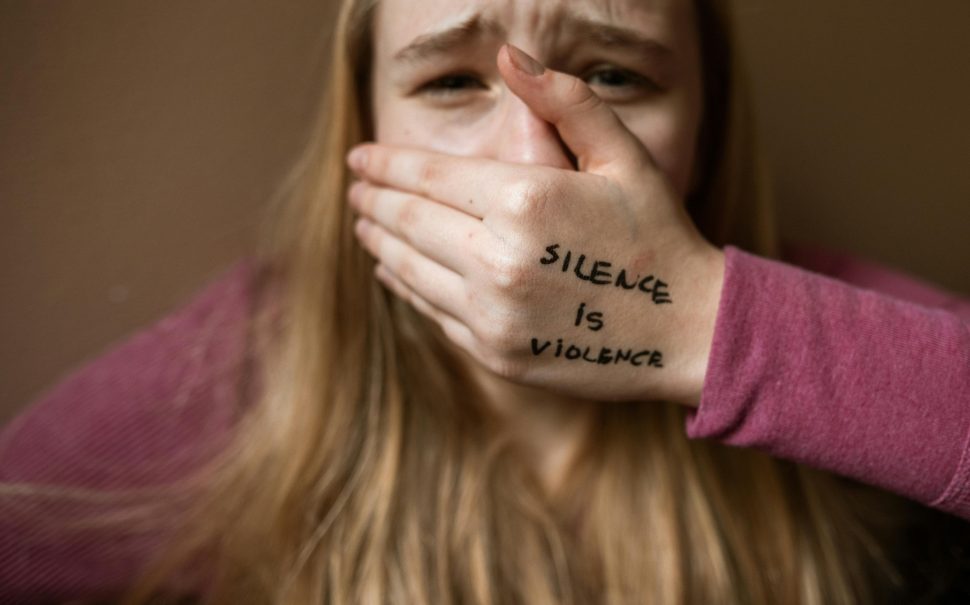

Featured image: Scared woman covering her mouth. Image provided by Pexels.