Cocaine and low-level public disorder are becoming increasingly prevalent in English football as the country returns to post-Covid normality, according to academic experts.

Professor Geoff Pearson, a senior lecturer in criminal law at Manchester University and leading expert in football hooliganism, believes a host of lockdown-related factors have caused the nationwide increase in fan disorder.

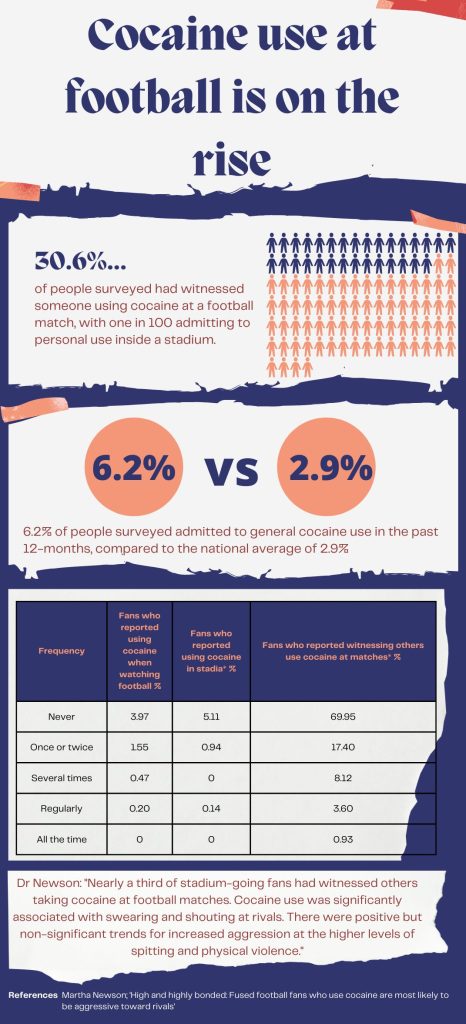

This comes after a research paper by Dr Martha Newson – published in the wake of the scenes that surrounded the Euro 2020 final at Wembley, in which thousands of ticketless fans stormed the stadium – revealed almost a third of football fans had seen someone taking the drug at a football match.

Pearson said: “I think the increase in lower level disorder – anti-social behaviour and low-level criminality and drug taking and that kind of thing – I think there are a number of lockdown related explanations for that.

“One of which is people just haven’t had the opportunity to get out there with their mates and have a bit of a sing song, get drunk and take drugs in social situations. People are catching up on that.

“The other explanation related to lockdown, there’s been a big turn over fans. There’s a lot of new fans who don’t necessarily know the rules and conventions about where the limits are and how to behave.

“A Lot of young fans, that for two years would have been slowly drip fed into football fandom, have suddenly arrived en masse, and that’s created a bit of an issue.”

The excitement of returning crowds for the 2021/2022 campaign soured quickly, with post-pandemic nostalgia giving way to abusive chanting, missile throwing and – in the recent case of one Nottingham Forest fan, who head-butted Sheffield United’s Billy Sharp – violent attacks on opposition players.

But the problems lie not just on the supporters side, with the pandemic forcing those in the security industry to look elsewhere as events, pubs and football shut their doors – with many staying put at jobs that are often better paid and less confrontational.

Police have also had two-years away from football in which fan-supporter relationships have dwindled, and Pearson explained that football policing relies upon the development of such relationships between fans and authority.

He said: “For two years, you just haven’t had those relationships and that’s damaged the extent to which the police officers know where risk at matches lies. It also has prevented them from laying down tolerance limits and negotiating behavioural limits with people.”

The rise in cocaine use is being seen on the ground and in the stands. Dr Newson’s study in July 2021 found that 30.6% of people surveyed had seen someone taking cocaine at a football match, while 6.2% admitted to general cocaine use in the last 12 months – significantly higher than the national average of 2.9%.

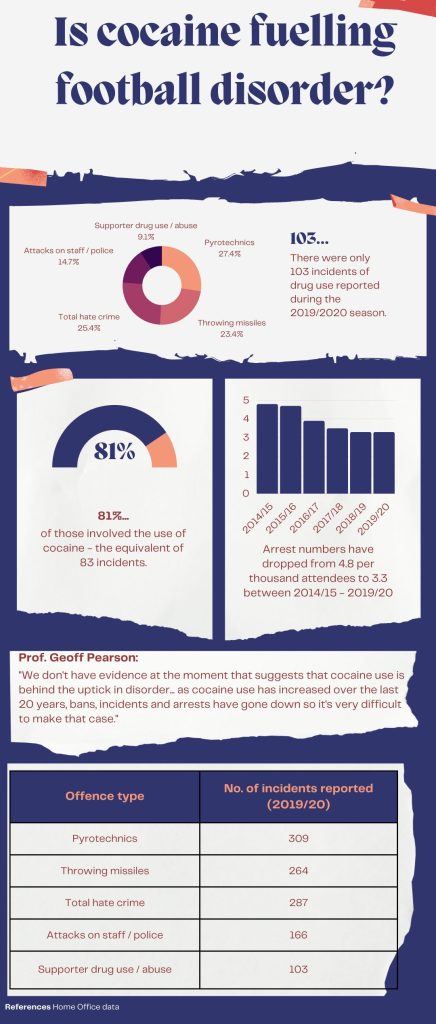

But despite the increase in prevalence of the drug, arrests and incident reports have remained relatively low. According to information gathered from the Home Office, there were only 103 incidents of drug use/abuse reported during the 2019/2020 season – the final full season before the pandemic – 81% of which involved the use of cocaine.

Furthermore, arrest numbers in and around football matches has decreased generally, with an average of 3.3 per 100,000 attendees in 2019/2020, compared to 4.8 in 2014/2015.

The data casts doubt into exactly how influential the rise in cocaine use has been on the rise in what Pearson described as ‘low-level disorder’.

He added: “We don’t have evidence at the moment that suggests that cocaine use is behind the uptick in disorder.

“The bottom line is if you drew a graph of cocaine use at football against football incidents and football arrests and banning orders, you would see that as cocaine use has increased over the last 20 years, bans, incidents and arrests have gone down so it’s very difficult to make that case.

“There quite clearly is a relationship between the type of person that might set off pyrotechnics and get drunk and the type of person that takes cocaine.

“It’s not at all a surprise that those groups which engage – that sort of push the edges in terms of transgressive behaviour – are also taking cocaine, but I think cocaine is an outcome of what those groups do rather than being a cause behind their behaviour.

“There’s a relation but definitely not a causation.”

Craig (a pseudonym used for anonymity purposes) has been going to Manchester City games and using cocaine for nearly two decades. He started taking the drug recreationally during the 1990s at clubs and illegal raves, before deciding to try it at a football game.

He now uses cocaine roughly once a month when attending a match, particularly if he is going to a big game or an away-day with a large group of friends – he insisted he had never done the drug when going with his two sons.

When asked why, he explained: “It’s everything that surrounds a match really, like going to the pub before and seeing your mates. If you’re going to have five, six, seven beers before the game why not have a bump or two just to kick things up a bit you know?

“It enhances the togetherness, that almost tribal connection between you and your mates and then against whoever’s in the away stand wearing different colours or whatever.”

And Craig added that he’s never felt a risk of getting caught with the drug, describing how security in and around the ground has never been stringent enough to pull him up – as is the same with the pubs and bars that surround the ground.

When asked about security at the ground, he explained that he smuggled the drugs in his trousers and that there is never more than a couple of sniffer dogs on site and the odd pat down.

He said: “I mean, what are they meant to do? There’s 60,000 people coming in through the turnstiles every game.

“At the pubs and bars before and after game. Same as anywhere else really – quick pat down, maybe look in your wallet – as long as you’re not f****d up, you’re in.

“I probably do more than most anyways, to be honest, some of my mates just have it in their pocket.”

The Premier League was asked for comment on the security protocols at the grounds.

A spokesperson said: “The Premier League condemns the use of drugs at our stadiums. Possession or use of cocaine is a criminal offence and can result in a football banning order.

“Ground regulations clearly state that drugs are prohibited and measures such as detection dogs are used frequently to combat it. Our clubs continue to work closely alongside the police on this issue.”

Manchester City were also approached for comment on the club’s individual security measures but did not respond.

Craig echoed a lot of Professor Pearson’s comments, agreeing that cocaine use in football has risen while maintaining it is not the drug that’s causing the problems.

He added: “I don’t think the problem is as bad as people make it out to be from being honest. It’s no different than it has been for the past 10-15 years.

“If anything, I’d say doing coke at the footy has become more common, but it’s become more normalised. People aren’t getting off their heads and smashing up stuff, they’re just doing a few bumps and enjoying the buzz with everyone around them.

“I mean look, when I go to game and I’m doing coke, I’m not screaming, I’m not swearing, I’m not throwing stuff or racially abusing any of the players or any of that.

“So, for me and my group of friends, I don’t think we’re really bothering anybody, to be honest.

“Like I said, we’re not throwing things, we’re not swearing, we’re not being aggressive, we’re just trying to enjoy our time as we can you know. That’s all I can say about it really.”