Instead of focusing on the ‘gender pay gap’ we should be looking at the ‘mothering pay gap’.

The gender pay gap is calculated by lining up men’s and women’s wages and making a median. This data does not account for nuances and differences in specific job roles, age, how many men and women work in a particular industry, or women with children or previous experience. The data is a measure across all jobs in the UK, not of the difference in pay between men and women doing the same job. It also does not consider what people studied at university and the field women and men are choosing to pursue and how this affects their wages. Rather than concluding that the gender pay gap is due to gender discrimination in the labour market (this is illegal as set out in The Equality Act 2010), these nuances and differences need to be analysed.

Parenthood is a major factor determining how many women are in the workforce. Rather than focusing on a gender pay gap, attention should be brought to the mothering pay gap and the reasons for this gap.

Why are women the ones staying at home or going part time?

The University College London (UCL) found that women returning to work after having their first child would earn on average 28% less in the first year. The study revealed that women experience a reduced salary of around £3,672 per year. The amount of earnings lost depend on how many children a woman has, whether she works part time or full time after having children and what type of career she has. Most couples who have children decide that the highest earner (generally the man), goes to work and the other person stays at home or works fewer hours.

Women struggle to return to full-time because their workplace does not offer remote work for them to be at home with their children. They are also not offered flexible working hours most of the time and are given part time roles instead. Mothers who are not given an option to work from home may have to take up part-time work as a result. They may even decide to pull out of work because they believe that part time is not worth it as there is not much wage progression. Monica Costa Dias, IFS associate director and an author of the report explained there are many reasons for the gaps in earnings of men and women but working part-time is an important contributing factor. She said “It is remarkable that periods spent in part-time work lead to virtually no wage progression at all.” Many mothers also want to be around for their child’s prime development years and also for practicality reasons such as breastfeeding, which is recommended to continue after the year maternity leave.

Why are women earning less than men?

Culture can influence people’s choices but the evidence suggests that this doesn’t play a huge role. In fact as countries become more egalitarian, meaning traditional gender roles are minimized and cultures become more gender neutral, the differences in choices of men and women maximise.

Multiple studies published in publications such as In Science and International Journal of Psychology have shown that although cross-culturally men and women are similar, the differences in personality traits between play a significant role in the choices that they make. For example, men are more interested in things whereas women are more interested in people. This is the largest psychological difference between men and women known so far. In order to become an engineer you have to be interested in things rather than people. Most of those people are men. If you want to become a nurse you have to be interested in people more than things. Most of those people are women. In the UK women make up 90% of all nurses and only 23% of the science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) workforce is female. Even more gender-equal countries produce comparatively fewer women in the STEM fields and women dominate nursing.

Women are generally going into fields that pay less. Let’s take the example of engineering and nursing. The average salary for an engineer is £48,000 gross per year. The average wage of a UK Nurse is somewhere around the £33,000 to £35,000 annually.

Attempts to ‘close the gender pay gap’ aren’t practical or helpful

The discussion around the gender pay gap has led some companies to put in quotas where they hire 50% women and 50% men. In theory this sounds fair but in reality it is not. Equality of opportunity gives free choice and people choose different things, so pushing for equality of outcome will take away choice. It is better to open up the market to all people regardless of their ethnicity or gender. Employers may not find 50% of men and 50% of women that are competent for the job. More men than women may apply for a particular job and more men may be competent for that job than women and vice versa. To get this 50/50 ratio it would have to be forced and therefore would take opportunity away from those qualified for the job.

The disaster of trying to enforce equality of outcome was exemplified when two white male creative directors at an advertising agency were fired on the basis of their sex. They were fired in order to increase female representation and change the company’s reputation of being “full of white, British, privileged men” according to a female director.

There is no correlation between sex and competence. Men and women are essentially equal in their intelligence, and they differ very little in conscientiousness. This is why the government and workplaces should focus on the mothering pay gap. If we want more women in the workforce we should give equality of opportunity to mothers and employers can do this by offering flexible work hours and allowing mothers to work from home if this is possible.

Having children impacts working women

Another reason women struggle to get back into the workforce is because employers see them as less valuable because they believe that their output will not be as strong due to having child commitments. One mother said that her boss sacked her after telling him she was pregnant. Another woman revealed that her work hours were incompatible with raising a child and requested to work part-time or on a job share. However, without any discussion she was fired. They were sacked for having children, not because of their gender.

Employers are also aware of women having children young. A survey of 500 managers showed that more than 40% admitted they are generally wary of hiring a woman of childbearing age, and 44% said the cost of maternity leave on their business is a significant concern. Participants said they would also be wary of hiring a woman who already has a child or hiring a mother for a senior role.

Small businesses struggle to take on pregnant women because they have to recruit someone on a temporary basis while the employee is on maternity leave. When the employee returns they often do not take up a full time position or may not return to work. Although employers can claim Statutory Maternity Pay back, not all of it will be claimed back due to the disruption in the business. If the government were to offer more financial support to small businesses this could help mothers stay in work.

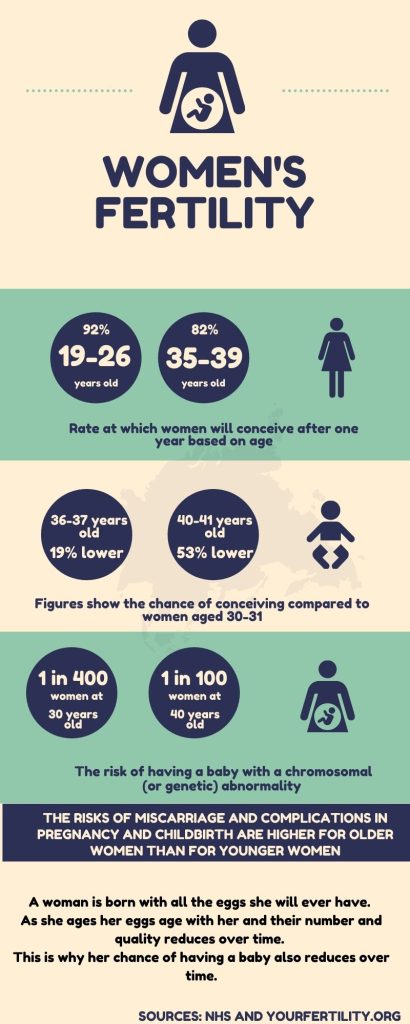

The prime years of career development is while people are young and climbing up the career ladder. If women have children young, they most likely have not yet climbed up the corporate ladder or received higher pay. Mothers find their careers become stagnated after having a child. However, many women have children earlier in life because of the biological factors of having a baby at an older age.

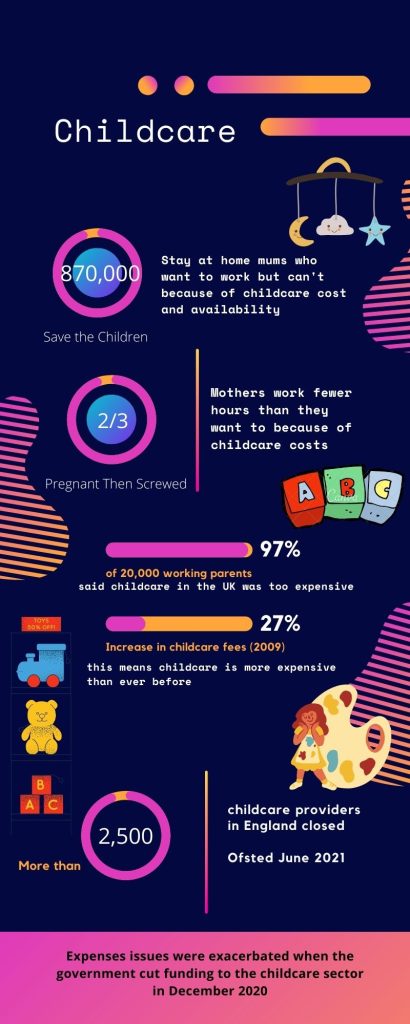

Expensive childcare is costing mothers their careers

The UK has the second most expensive childcare system in the world. A study conducted by UCL revealed that mothers need better and affordable childcare if they wish to return to work or work full time. The median salary is £585 a week and yet parents with two children are spending an average of £526. Most women are staying at home because going to work would mean spending more money on childcare than what they earn. Some mothers make the choice not to go to work and others do not have a choice.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ paper ‘Does more free childcare help parents work more?’ revealed that full-time early years childcare rather than part-time is crucial for getting women back into the workforce. The study was conducted in England and found for mothers whose youngest child is eligible, free part-time childcare “only marginally affects” female labour force participation. However, full-time free childcare led to “significant increases in labour force participation and employment”.

The government offer 30 hours of free childcare per week if the applicant lives in England and has a child between the ages of three and four. However, maternity leave is only for a year which leaves mothers with children younger than three struggling.

The data suggests that having children will inevitably have an impact on women’s career trajectory and earnings. To close the mothering pay gap the government need to support small businesses to help them keep mothers in employment. Workplaces, if they are able to, should offer mothers flexible working hours and an opportunity to work from home. Equality for opportunity for everyone is the way forward.