“Everyone just assumed I was being lazy or not trying hard enough” . Each week, the monotone voice would reel off sums which came from a CD player sat at the front of the classroom, with each sum her frustration would grow as she would stare down at the empty answer boxes on her A5 sheet of paper.

Her paper would be handed in as blank as it was when she started.

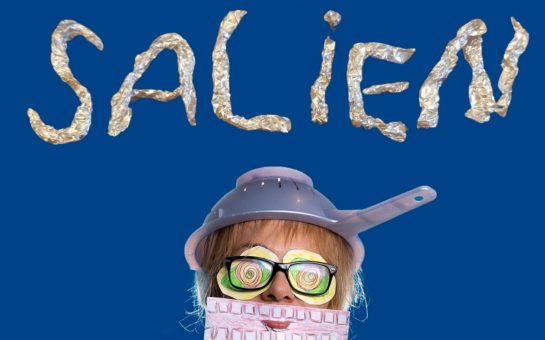

This is Bonny Hazelwood, 20, from Brighton. She first noticed she was neuro diverse when she was forced to sit weekly timed mental maths tests in in primary school.

“I wouldn’t get a single answer down I would just sit there miserable. Everyone just assumed I was being lazy or not trying hard enough,” she tells me.

Bonny is not alone in her experience, ‘lazy’ is a word people with a condition called dyscalculic are often labelled with at some point in their life.

According to the British Dyslexia Association (BDA) dyscalculia is a “specific and persistent difficulty in understanding numbers which can lead to a diverse range of difficulties with mathematics.”

However, the prevalence of this disability is hard to suggest because definitions and diagnosis of dyscalculia are still in their infancy.

This official definition was only released in summer 2019 despite 5% of the population being affected by dyscalculia.

The impact this condition can have on people’s lives can be massive so how come there are so many people that have never even heard of it and why is it so behind the likes of dyslexia and other learning difficulties?

As someone who is also dyscalculic (diagnosed just before secondary school) I can relate to Bonny’s experiences.

I still vividly remember the feelings of dread and anxiety that would consume me every single day as I would wait in line outside my maths classroom.

Like Bonny, I started to notice my brain wasn’t like the other people’s when I was in primary school.

In one maths lesson the teacher called us to the front of the class one at a time to stand in front of an interactive clock on the white board.

The fingers would spin around and we would have to stop the clock when it landed on a certain time.

I still remember how my legs would begin to shake the closer it got to my turn, how the feelings of nausea and panic would consume me instantly.

It would make me so dizzy I was sure I was going to faint.

I used to silently pray the teacher would have mercy on me and give me a simple ‘o’clock’ time, at least I knew that meant one of the hands needed to be pointing at 12 even if I wasn’t sure which one.

When it got to my turn I stood in front of the whiteboard red-faced and mortified as the dreaded clock loomed above me.

I would be reeling from the panic so much so that I could barely hear what my teacher was even saying to me.

Not that it mattered; I was never going to get the right the answer any way.

I was 10-years-old and could not understand why I did not know how to tell the time properly when all the other children around me could.

It wasn’t just that I was not very good at maths it was that no matter how many times something was explained to me involving sequences, quantities, or any mathematical procedure it just didn’t make any sense.

No matter how hard I tried it was as though my brain just couldn’t comprehend.

In simple terms, dyscalculia is like dyslexia but with numbers.

However, it’s more than just not being able to recite all your times tables (which I still can’t do).

Dyscalculic people can struggle with sense of direction, processing information or map reading.

Rules of card games, still having to count on fingers, not being able to work out change or learning to tell the time – don’t even get me started on the 24-hour clock.

Dyscalculic people feel it’s impact in everyday life.

It crops up in day to day tasks most people would take for granted such as calculating measurements and timings for cooking or route planning for a new location.

A dyscalculic is forced to find a way around it that helps them cope.

Tony Attwood, Head of the Dyscalculia Centre in London, says dyscalculia is where dyslexia was around 30 years ago.

“It’s a much more complex genetic disorder that hides in the shadows and there are all sorts of issues lurking around it. Not only is it more difficult to understand, as well as it’s late arrival, but there is also a general acceptance around not being good at maths.”

It’s true.

Whenever I tell somebody that I can’t do maths it’s often laughed off and met by people telling me their rubbish at maths too.

Whereas, if you heard someone openly admit that they couldn’t read or write to an acceptable standard you be unlikely to react in the same way as it would be seen as taboo in this society.

So, by creating this narrative that ‘everybody is a bit bad at maths’ are we collectively masking the fact that there are many unidentified dyscalculics out there in our society and undermining the real struggles they experience?

Brenda Ferrie, Dyslexia and Dyscalculia Specialist at the British Dyslexia Association tells me that up until now it’s always been blamed on bad teaching and lazy children.

“It’s the same as it was for dyslexia but now there is a lot more interest and research in dyscalculia. There is a specific area of the brain that is under developed so it’s not functioning properly and it’s hereditary.”

Brenda tells me how much of a difference having a formal definition of dyscalculia has made to helping fellow dyscalculics. “It shows that it really does exist which means we can test for it and give people a proper diagnosis,” she says.

Due to the lack of awareness and testing, Bonny wasn’t formally diagnosed until she was 19 which meant she didn’t receive proper support until she was in her first year of university.

This meant she was faced with multiple battles during her time at school due to her condition being so misunderstood.

“One teacher approached me and just outright told me she thought I could be autistic, another tried to give me Sudoku’s in the hopes it would straighten out my maths problems.

“It even got to the point where although I was so obviously struggling with my maths and always had since I started school, when it came to sitting my GCSE’s the teacher insisted I enter for the higher maths paper,” she says.

The underlying anxiety that stems from inadequate teaching not suited to a dyscalculic person’s brain can be damaging for students and continues to follow them into adult life.

“I know for me it was a massive struggle. To this day it’s a miracle I passed my maths GCSE,” Bonny adds.

Like Bonny and I many other dyscalculics will go through similar frustrating experiences during their time at school.

Something which Tony tells me is common.

“The real tragedy is dyscalculics go through life feeling like an idiot,” he says.

“They feel blocked from doing what they could be quite good at because they can’t do something that everyone else around them can and feel stupid.

“When in fact it’s because using the same method of teaching doesn’t work with dyscalculics brains,” he adds.

I relate to what Tony tells me as I still have feelings of shame when admitting that it took me four attempts to pass my maths GCSE.

I was told I wasn’t allowed to take certain A-levels because I did not have a ‘suitable grade’ in my maths.

Whilst my peers got stuck into their new exciting A-level topics I was forced to sit in a classroom revisiting my secondary school syllabus that still filled me with the same stress and anxiety it did during primary school.

It also meant that, without it, I wouldn’t be able to progress to university to study my dream career in journalism, despite there being no correlation to maths.

I’m not alone as Tony continues to tell me: “I’ve had adults come to me saying they just thought they were an idiot and I think that’s really quite profound. There’s really bright people who think they are so stupid because of this condition.”

“If you’re dyslexic and you don’t know how to spell ‘receipt’ it doesn’t stop you learning how to spell ‘because’, whereas dyscalculia is purely sequential, you can’t do multiplication without knowing how to add. I think a big step forward is knowing that it’s not your fault,” he adds.

Brenda tells me that humans are born with a sense of number, it’s part of our survival mechanism but dyscalculic people tend not to develop these numerical reference points innately they have to be taught.

“For example you could have a group of apples and pears and the apples may be bigger in size compared to the pears but there’s a larger quantity of pears. For a dyscalculic person it won’t be an instant reaction, it takes an extra amount of time for their brain to recognise that,” she says.

“It can be very debilitating not having that natural instinct for numbers, it creates anxiety and worry and can be a huge emotional setback for some dyscalculics.

“It can be a question of not taking certain opportunities or avoiding certain jobs in case they require any kind of relation to numbers.”

Bonny finds processing information is one of the main issues she deals with.

“It can crop up in lots of different ways. When people talk to me and say something too quickly it will go in one ear and out the other and I won’t have processed it at all.

“If they have never met me before they might be annoyed and think I’m not listening. They don’t get that I might need a little bit longer to respond or some extra time to work something out,” she says.

During her fresher’s week at university, Bonny went to play a game of pool with her new flat mates.

“I just couldn’t put it altogether in my head when it came to getting the cue lined up to the balls. It was quite overwhelming. I just wanted to socialise with my new friends but also not cause a fuss and have to bring it up,” she says.

Luckily for Bonny her university offered free assessments and getting a formal diagnosis meant she could receive support from a personal tutor which was funded by disabled student allowance.

She said: “I wanted the official diagnosis for validation and I’m very lucky to have one. People think you make it up and that it’s a fabricated thing.”

Bonny says her diagnosis was incredibly beneficial and hopes to become an occupational psychologist after her degree. “The diagnosis has given me a path in life I would never have been inspired to do if I hadn’t been identified as dyscalculic.”

She adds: “People need to understand that it exists and it is common. Many people are dyscalculic and most of us are probably not diagnosed or identified. It is a real serious thing.”

So next time you’re out and about just remember you have probably been served by a dyscalculic at some point in your life.

The server isn’t incompetent when they’re relaying your order back to you for the second time or if they’re taking a little bit longer to get you your change.

The person who double booked your appointment didn’t mean to mess up your plans that day.

And the person who approached you and asked for directions isn’t trying to annoy you when they ask you to repeat it, they’re probably stressed from getting lost for the fourth time that day after finding Google Maps confusing.

To all my fellow dyscalculics out there just know that it’s not a childhood phase, or something that stops when you leave school, it’s not just a numbers thing, or an academic thing.

It’s a very real condition and it’s who you are as a person it just means we have to do things a little bit differently sometimes.