To tick the boxes of a sporting all-rounder today, you could both take wickets and score runs on the cricket field, or maybe set up goals and defend your own on the football pitch.

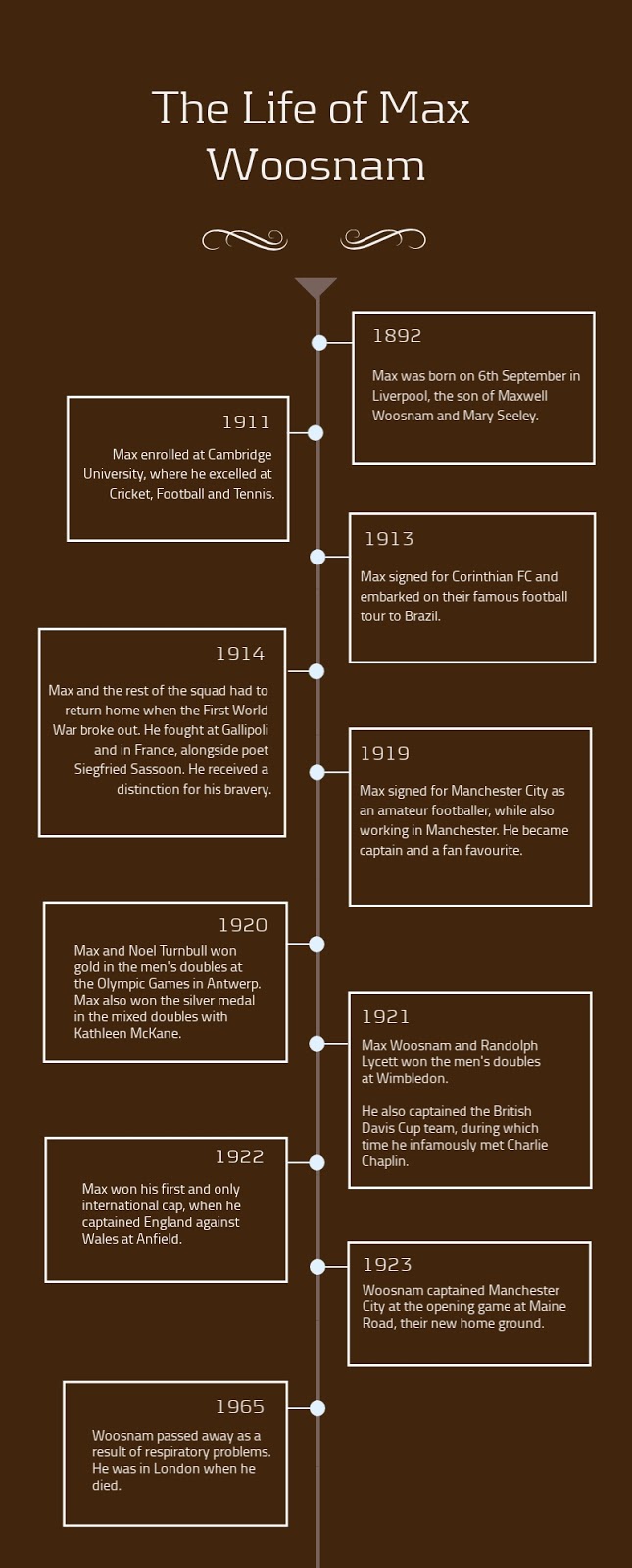

Max Woosnam created his own boxes to tick. He was a Manchester City and England footballer, a Wimbledon champion and an Olympic gold medallist.

He rubbed shoulders with world stars and took them on in their own home, and bravely fought when called upon when the planet plunged into war in 1914.

What Max Woosnam achieved in his life went beyond sport, but it is sport where he will be fondly remembered, or perhaps forgotten, as one of the greatest ever.

He was born in 1892 into a family of landed gentry. His father was the Archdeacon of Macclesfield and he lived in mid-Wales for most of his childhood.

Woosnam attended Winchester College, where his sporting exploits began. He captained the golf and cricket teams, while also playing squash.

His finest hour while at the college came at Lord’s cricket ground, when he scored 144 not out for the Public Schools XI against the Marylebone Cricket Club.

Continuing his fine sporting form, he attended Cambridge University in 1911. It was at Cambridge where he started his tennis career, as well as representing the prestigious institution at cricket and football.

LOW BUDGET STAR: Max Woosnam refused to accept payment for his sporting exploits

In 1913, Woosnam was invited to join Corinthian FC, a well-known football club based in London, on their tour to Brazil. He signed for them in the same year, and also played the odd game for Chelsea in 1914.

The Corinthian squad were called home from the tour amid the outbreak of World War One, Woosnam faced a treacherous journey back before immediately enlisting for the Montgomeryshire Yeomanry.

Woosnam fought in the unsuccessful Gallipoli campaign which lasted eight months between 1915 to 1916, where it is estimated that around 21,00 British Empire troops were killed.

After that, Woosnam was sent to the trenches in France where he fought alongside the famous war poet Siegfried Sassoon. Both men received distinctions for their bravery upon their survival.

The war concluded and Woosnam resumed his sporting exploits. In 1919, he began playing at centre-half for Manchester City as an amateur.

Ernest Mangnall, who managed Manchester City from 1912 to 1924, once said of Woosnam: “I have known time after time when the arrival of Max Woosnam in a town has been regarded as a social function in itself. People have swarmed around the team on arrival and have excitedly asked if he were with them.”

The idea of being paid to play as a professional seemed ‘vulgar’ to Woosnam, who was one of the many of his era to participate through their love of sport, with no financial gain.

He didn’t play in away games, which caused hostility from the club’s supporters towards Woosnam’s employers, as City’s results on the road dwindled.

In 1921, the Daily Mail reported Woosnam’s performance from a 1-0 victory against Chelsea.

It said: “The outstanding feature of the game was the wonderful play of Max Woosnam, the City centre-half, who was by far and away the best player on the field.

“The first-time passes to the forwards were splendid, while if the backs were in difficulties the Old Cantab was always there to help them.”

In the early to mid 20th century, it was not uncommon for men to be both first-class cricketers and international footballers, or vice versa.

Arsenal and English cricket’s Denis Compton and Hampshire and English football’s Ted Drake are among those to have mastered both fields.

But it was in 1920 when Woosnam burst on to the world stage of tennis, extending his incredible career. At the Olympic games in Antwerp, he and his partner Noel Turnbull won gold in the men’s doubles, and silver in the mixed doubles with Kathleen McKane.

Below is a video that shows the attendance of spectators and the dress code of the players who competed at Wimbledon in Woosnam’s era.

In the following year, Woosnam partnered up with Randolph Lycett to win the Wimbledon men’s doubles title, he also captained the British Davis Cup team that competed in America.

It was during this trip to America that the British side were invited to meet Charlie Chaplin at his home, and it is fair to say Woosnam left his mark.

He beat Chaplin at a game of tennis, and is also said to have beaten the Hollywood star at table tennis, despite using a butter knife instead of a bat. It is also said that the pair took an immediate dislike towards each other as Woosnam was not keen on Chaplin’s ego.

He did not experience as much success in individual disciplines. He was unfortunately beaten by Sir Cecil Campbell in the 1921 Wimbledon men’s singles, but the Daily Mirror credited a great display.

They reported: “Woosnam played a wonderfully animated game. Many of his shots could not have been better, but perhaps, his game would lose nothing if he restrained his very energetic rushes after impossible balls.”

In 1922, Woosnam resumed his football career and was awarded his sole England cap when he captained his country to a 1-0 victory against Wales at Anfield.

Possibly one of Woosnam’s proudest moments came in the following year, when he captained Manchester City in their first ever game at Maine Road upon its official opening, with the Lord Mayor present.

HONOUR: Woosnam presenting the Lord Mayor of Manchester to each player at the Maine Road opening in 1923

Unfortunately, 1923 was also the year Woosnam suffered a broken leg, an injury which would have a lasting effect on the rest of his career.

Between 1924 to 1926, Woosnam played sparingly for Northwich Victoria but called time on his career after different injuries prevented him from regular appearances.

He finished his illustrious sporting career having been an international footballer, an Olympic gold medallist, a Lords’ centurion and a Wimbledon champion.

And if I forgot to mention, he was also a scratch golfer and made a maximum 147 break at the snooker table as well.

He worked for ICI, a chemical industry, in his later life until his death in 1965 which was caused by respiratory problems, possibly down to a life of heavy smoking.

A career like this could only be a dream in the modern sporting world, with each athlete bred and trained for specific sports and positions.

Nonetheless, not only the career, but the life of Max Woosnam keeps his place safe in history as one of Britain’s great but forgotten icons.