As the threat of the coronavirus has continued to spread throughout Britain, so has the quest to develop a vaccine.

In March, the first human trial of a vaccine to stop the pandemic began in Seattle in America, however it will be many months until the results of this trial will be discovered.

If a potential vaccine is to take on a similar model to the current national flu immunisation programme, it could be some time before we see progress on a mass scale.

In 2012, the Department of Health, Public Health England and NHS England decided to begin the programme the following year.

It also began a distinct branch aimed at childhood with an end goal to give influenza vaccinations to all young people aged between two and 16.

Within it was a school pilot programme, which was extended to target primary school-aged children in geographically distinct areas of the country.

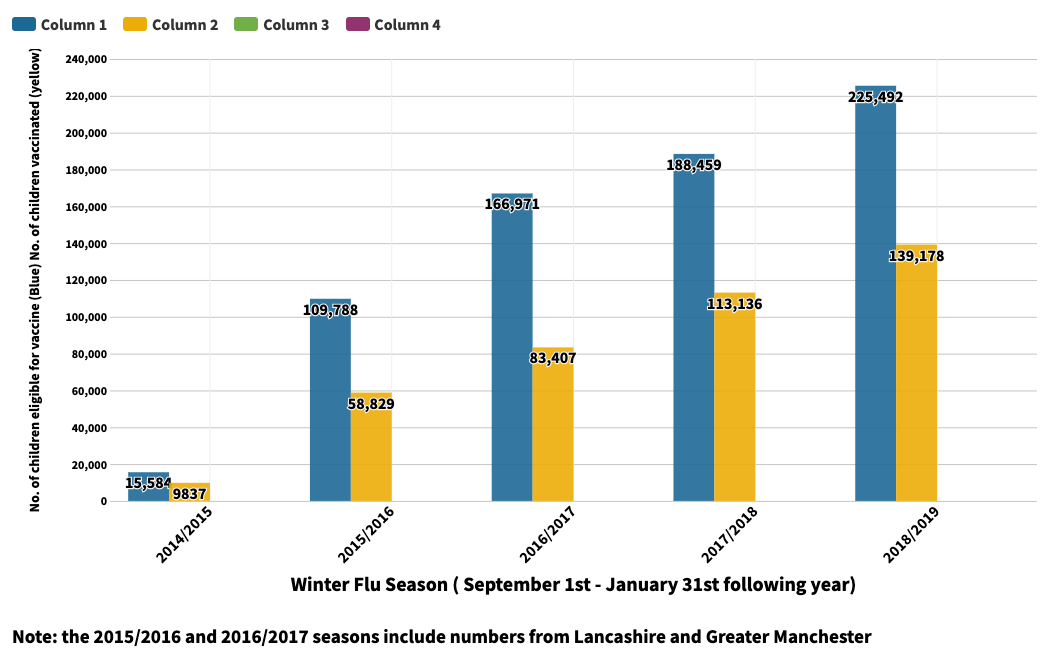

Since 2014, there has been a large increase in the number of children in Britain that were given the Influenza vaccine, as a result of the National Flu Programme.

Below is the table that shows the increase in the amount of children in primary school 1,2,3,4 and 5 in Greater Manchester that were eligible for the vaccine, and the amount that were vaccinated in each winter flu season since 2014.

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-flu-reports

The aims of the childhood branch of the National Flu Immunisation Programme foreshadow the aims of the entire effort; to increase the uptake of flu vaccination for those who are eligible.

On March 22 2019, the annual programme’s letter stated that there would be certain groups of people who would be eligible and prioritised for the vaccination in the winter of 2019 to 2020.

This included children aged between two and 10 years old, as well as pregnant women, people aged 65 and over and other clinical risk groups.

Who is most at risk when contracting the flu?

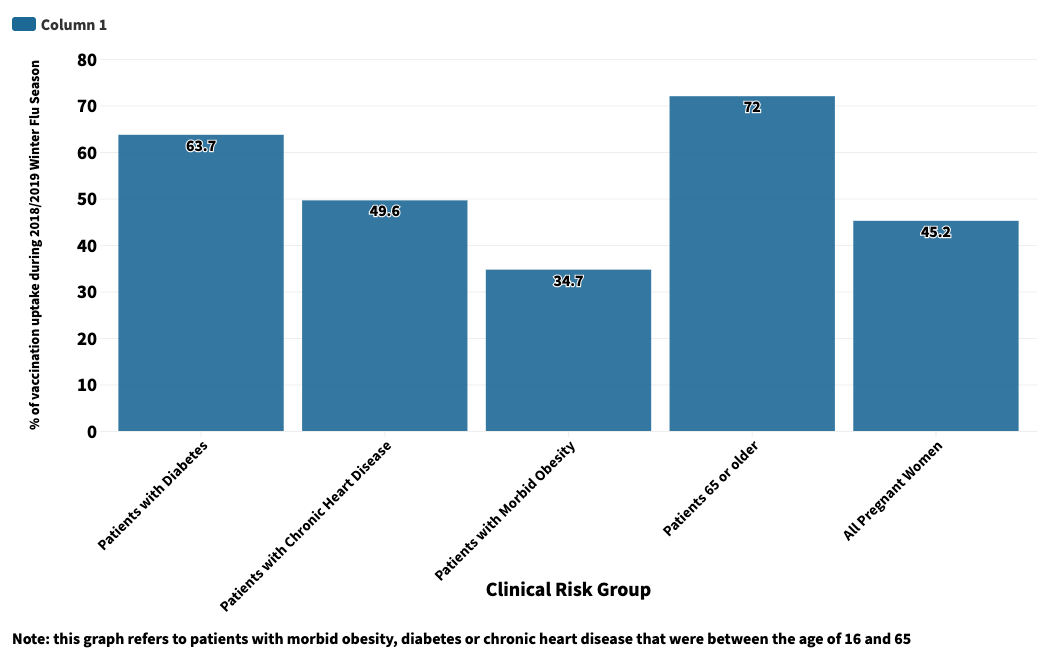

Clinical risk groups include people who are most vulnerable to flu, this is where the Coronavirus carries similarities as its contagious nature presents a threat to these same groups.

Pregnant women, people with diabetes, chronic heart disease and children under six months old are amongst those to be most vulnerable to flu.

Flu causes complications such as bronchitis and sinusitis, mostly found with children. Meningitis and primary influenza pneumonia can be products, yet uncommon products of flu.

The graph below shows the proportion of people in different clinical risk groups who were eligible for and received the flu vaccine during the 2018/2019 winter flu season.

Source: Public Health England

Source: Public Health England

A vaccine not only protects people from death, it prevents the spread of flu to those around them and it can reduce the pressure placed on the NHS if more people become immune.

It is also important to increase the effectiveness of the vaccine each year. Vaccine effectiveness, as much as it is an approximate statistic, is a figure adjusted by the consideration of different variables such as age-group, sex and pilot area.

In the 2018/2019 winter flu season, the vaccine effectiveness was 48.6% for 2-year-olds to 17-year-olds and 44.3% for all age groups.

The programme adopted the World Health Organisation recommendation to aim for 75% uptake in clinical risk groups in the 2019/2020 winter season, meaning three-quarters of all adults who are eligible would be vaccinated. The results for this season are yet to be published by the government.

What vaccines are available and how is the search being escalated?

In Britain, there are two main types of flu vaccine. An inactivated vaccine is given by an injection and a live attenuated vaccine is given by nasal application.

These vaccines protect against two viruses of influenza: Influenza A, which causes seasonal flu and potentially a pandemic, and Influenza B, which mutates at a slower rate than A. These are then divided into two further types of vaccine: Trivalent and Quadrivalent.

Last month, Dr Melanie Saville, from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), suggested that an eventual vaccine could need emergency authorisation for use, considering the normal timeframe for vaccine productions could be up to 20 years.

CEPI is a global partnership that was formed in 2017. The group’s aim is to accelerate the quest for vaccines against infectious disease and is currently playing a vital role in funding the international effort to find a Coronavirus vaccine.

On April 1, the Norwegian Government announced that they will inject 2.2 billion Norwegian Krone for CEPI to continue pursuing the vaccine.

Upon the announcement, CEPI Chief Executive Officer Dr Richard Hatchett said: “We hope to deliver a safe and effective vaccine within 12 to 18 months, but we can only do this through a coordinated international effort, the likes of which have never been seen outside of war.

“Developing this vaccine and, most importantly, making it globally accessible, is our only long-term path out of this pandemic situation.”

The National Flu Programme has been successful in the vast increase in children and older people who have been made eligible for the vaccine. From 2014 to 2019, the number of children vaccinated in Greater Manchester alone increased by nearly 130,000.

A model as effective as the National Flu Programme would need to be condensed into the incredibly short time frame that Dr Hatchett is hoping for, in order to mass-produce an effective antidote to the Coronavirus.

The key issue with the development of a vaccine is that this urgent need for immunisation is unprecedented, and the world’s scientific capacity will be pushed two its limits like never before.