“50 years from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county (cricket) grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers, and – as George Orwell said – old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist.”

So said former British Prime Minister John Major in 1993. Interestingly, this was his vision of Britain in Europe.

However, does his view of English county grounds reflecting the British character still resonate nearly 30 years on?

Much has been made over significant changes to the English game of cricket over the last 20 years or so.

From the advent of Twenty20 revolutionising world cricket from England in 2003 to a decline in attendances across the world and England’s triumph in the 2019 World Cup, the game has been through a lot.

One factor that has always remained with cricket, and it does also apply to many other sports such as hockey and rugby, is that it is an exclusive sport played by those from a better off background.

A report by the Sutton Trust in 2019 showed how cricket ranked highest, above rugby union and Olympic medalists, in terms of the percentage of professional players who attended independent school.

With the 2019 sports personality being won by England’s World Cup and Ashes hero, Ben Stokes, and the England cricket team as a whole winning the team of the year at the competition is cricket closer to the people than ever before?

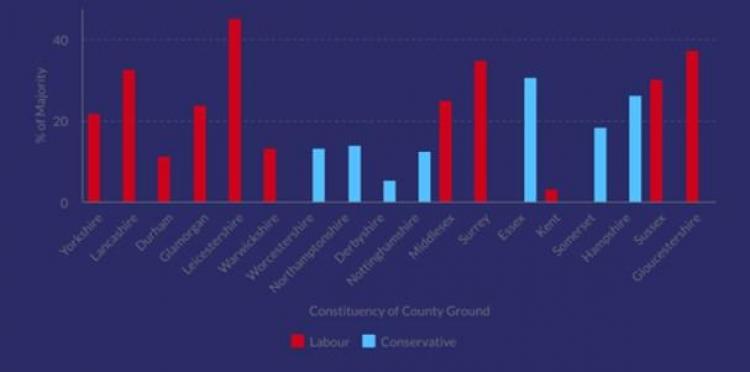

The spread of county championship grounds in relation to their parliamentary constituency brings up what may be an unexpected result for many people who believe cricket to be an upper class game.

The majority of the 18 first class grounds are situated in Labour constituencies, with only Kent’s ground in Canterbury not commanding a decent majority of the vote.

Many of these constituencies have also recently changed parties in the last two elections.

Kent famously switched to Labour in 2017, having traditionally been a Conservative safe seat, with a large student population being blamed for this.

Derbyshire’s ground in the Derby North constituency is very much a swing seat with it switching between Labour and Conservative on many different occasions over recent elections.

The Liberal Democrats also controlled three of these county grounds until 2015; Somerset, Hampshire, and Gloucestershire, with these losses to the two main parties creating the polarised picture of county cricket politics we see today.

While the political landscape of English county cricket may give us some indication as to how closely related the sport of cricket is to the public, it is more the makeup of these teams and the national team that will answer this question.

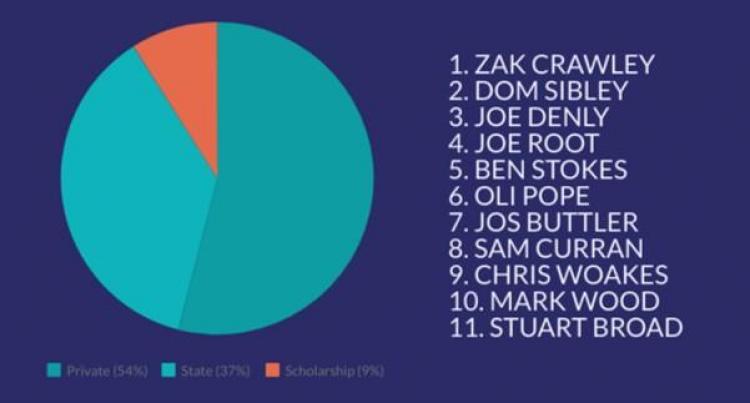

While the England team does vary a lot its composition of state or privately educated players tends to stay fairly similar.

As an example, the starting XI that started the fourth test vs South Africa is very even in terms of education, with many variables to this.

As most people would probably guess there are more privately educated players in the England team compared to those that are state educated.

Joe Denly, Ben Stokes, Chris Woakes and Mark Wood are from various parts of England and are the only players to have been fully state educated.

One variable in this squad is that the captain, Joe Root from Dore, Sheffield, was in state education before being offered a scholarship at an independent school.

This is a variable that the England Cricket Board (ECB) likes to stress that many players start off in state primary education but win scholarships to fee paying schools with a strong track record in sport.

However, as only 7% of English children are in private education, it must be said that having a cricket team that gets 54% of its players from the private school system, may not be representative of the country as a whole.

Compare this to football where the England men’s team is often over 80% state school educated, and cricket is always going to look unrepresentative.

Although, compare cricket to rugby and the numbers are pretty much even between the two, highlighting that this is not just a problem for cricket.

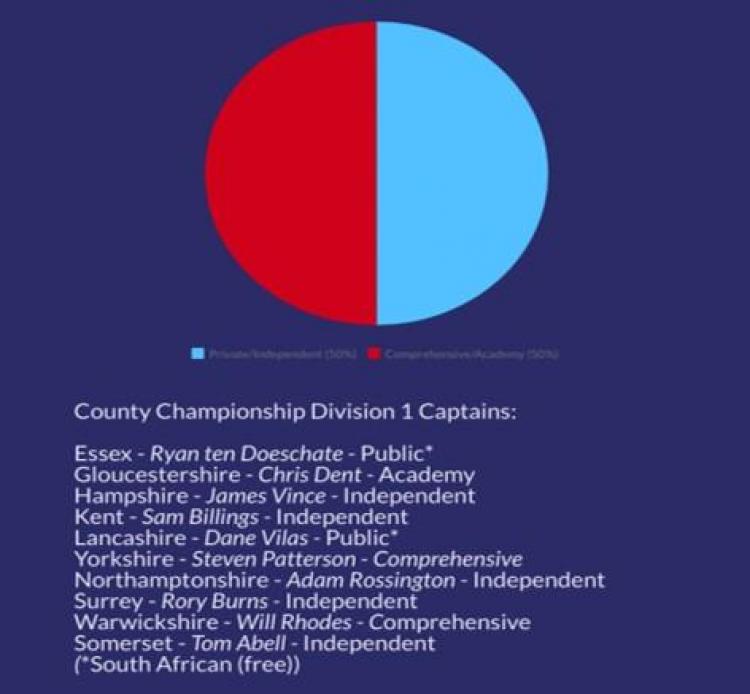

Further down the structures of professional cricket in the county game the results for the education of the captains of division one teams is evenly split.

50% of captains attended an independent school with the other 50% going through state education before becoming professionals, with many of these also going on to play for England.

Overall, while a large percentage of those who play professional cricket are from an independently educated background, especially compared to the population as a whole, this does not consign cricket to the label of an ‘upper-class’ game.

The percentage of privately educated players in many sports is significant and an issue that should be and is being addressed.

Cricket leads the way with many charities, including: Chance to shine, Wicketz, and Cricket without boundaries, providing cricket for disadvantaged people.

Hopefully England’s recent triumph in the World Cup can inspire a new generation to take up cricket, where educational and family backgrounds are irrelevant.

Image courtesy of JR P via Flickr, with thanks.