The Manchester-born guitarist for legendary American Beat poet Allen Ginsberg returned to his birth-city this week for a celebration of the 60th anniversary of the poet’s groundbreaking 1955 epic Howl.

Steven Taylor, who toured with Ginsberg for almost twenty years until his death in 1997, performed and spoke at Still Howling, an event which took place at The Wonder Inn on October 10.

It was the first time he had returned to visit his birthplace of Gorton in over 40 years after touring the globe with one of the world’s most renowned poets.

He said: “I’ve always had tremendous nostalgia for the place. The difficulty of being different in a foreign land makes the home town important.

“I’ve come through the city a couple of times with Allen and my band, but always for one night and in unfamiliar districts. This is big for me.”

Steven first started working with Ginsberg after being introduced to him by a professor whilst at college because Ginsberg was on the lookout for a guitarist.

Their relationship was productive from the very beginning, as Steven had to perform with Ginsberg immediately.

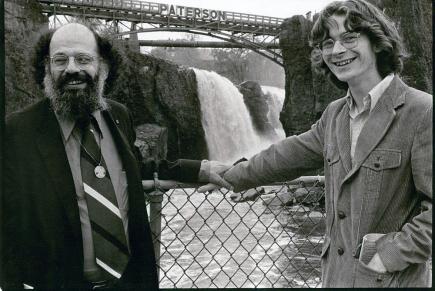

FRIENDS: Poet Allen Ginsburg (left) with Manchester-born guitarist Steven Taylor (Pic: Terry Saunders)

“The actual first impression happened on stage in poetry and music. I was playing along with songs that I had never heard before, and I thought they were terrifically clever,” he said.

It is this role as a vital link between the different artistic forms of poetry and music – a role in which Steven Taylor played a major part – that ensured Ginsberg’s influence would be so far-reaching.

For Ginsberg, the aural aspect to poetry was paramount – the musicality of the natural rhythm and intonation of the spoken word was an interest of his inspired by Ezra Pound.

Steven referenced Bob Rosenthal, Ginsberg’s secretary, who pointed out: “when Allen wrote a new poem, before he committed it to a book, he’d perform it dozens of times for live audiences all over the country – like a jazz musician refining a new piece on tour before committing it to a record.”

The importance of poetry as something to be heard is central to Taylor’s involvement with the Beats.

He chaired the committee at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, which preserved and ensured public access to thousands of audio recordings of Beat poets and writers performing at the university.

These recordings document an important historical shift from poetry on the page to performed poetry that continues today, as demonstrated by performances at Still Howling.

Performance poetry together with music has significant foundations in the San Francisco Renaissance in the late 40s, which drew inspiration from jazz-influenced poets like Langston Hughes in the 1920s.

MEMORIES: Steven Taylor recounted tales of his days with Ginsberg at Still Howling

Ginsberg and the other Beats popularised these performances in coffee shops and bars, most notably at the Six Gallery Reading in 1955, where Howl was first performed to an audience.

Steven said: “Then aural poetry came to New York. Allen told me that it was considered so unusual for poets to read in coffee houses that the New York Daily News did an article about it.”

This shaking-up of the way poetry was perceived as an art form was to have a global impact, as can be seen in Manchester and in the city’s cultural heritage.

John Cooper Clarke – perhaps Manchester’s most influential poetic voice of recent times – is an obvious connection to this favour for performance poetry instigated by Allen Ginsberg.

Another celebrated performance poet, Clarke primarily released his work in audio format with musical accompaniment from his band The Invisible Girls.

The parallels are clear: the relationship between Clarke and his band, which was led by legendary Joy Division producer Martin Hannett, echoes that of Allen Ginsberg and Steven Taylor.

Ginsberg’s relationship with Manchester can be traced throughout the city’s musical history due to his early efforts in ensuring that the Beat generation succeeded as a cultural movement.

Steven explained Ginsberg’s extensive influence on the early movement: “He was influential, starting on a small scale in his social circle in the early 50s, when he pushed everyone to publish.

“He got Burroughs a first publisher, acted as agent for Kerouac for a time, insisted that Gregory Corso perform and publish. In a sense, he made the Beat movement.”

Therefore Ginsberg can be credited, to significant degree, as influential in every piece of art that claims to have been inspired by the output of the Beat movement.

A primary example is in punk: a movement which jump-started Manchester’s musical dominance in later years with Buzzcocks’ DIY organisation of The Sex Pistols’ performance at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976.

Symbolising the relationship between punk and the Beats, Joe Strummer famously invited Ginsberg on stage with him in 1981 in Manhattan, referring to him as ‘President Ginsberg.’

The pair performed together on The Clash’s album Combat Rock from the same year, with Ginsberg providing spoken word parts to the song Ghetto Defendant.

Alongside his Beat commitments, Steven has been a member of influential proto-punks The Fugs for over 25 years and was part of 1980s punk band False Prophets.

He suggested that the compatibility of Beat and punk lies in the fact that both ‘tend to foster misconceptions regarding history,’ drawing criticism from people mistaking the knowing choice to focus on the moment over honouring old, established forms for a lack of knowledge and skill.

“The Beats were not illiterate yobs glorifying illiterate yobness; neither were the founders of punk ignorant of the roots of rock and the larger context of art,” he added.

This accessibility and immediateness that Beat and punk shared would go on to influence more of Manchester’s musicians in years to follow.

Joy Division would pay explicit homage to the Beat movement with the lifting of the title of their song Interzone from the short story collection by William Burroughs, for whom Ginsberg worked as an agent early on.

At the Still Howling event, The Isnes – an offshoot from Manchester band Folks – and Brighton based Chris TT both performed, acknowledging the influence of Ginsberg on their ongoing projects.

The relevance of Steven Taylor returning to Manchester in order to celebrate at Still Howling therefore goes far beyond his own personal heritage.

When asked about Ginsberg’s relationship with the city, Steven provided another perspective.

He said: “Allen started out a Marxist, going to university at seventeen with the intention to become a labour lawyer to help the workers.

“The industrial mind that inspired his Beat rebellion starts in Manchester. If you read Engels, you’re in Manchester.”

Unfortunately Ginsberg only came to read in Manchester once, which is in a sense even greater testament to the far-reaching influence of his work with its impact on the city.

However, his reading on June 5, 1979 at the Library Theatre – below the Central Library that still stands by St. Peter’s Square today – does provide another major connection between poet and city.

The reading took place, at the suggestion of fellow poet Anne Waldman, at a fundraiser for the Tibetan Buddhist Centre in Chorlton, organised by Lama Jampa Thaye.

It was not well documented: the only photograph was taken by Salford photographer Kevin Cummins and only one review was written for the New Manchester Review.

Organiser Lama Jampa Thaye remembers: “The reading itself was a great success. Allen read Howl and others including, at my request, Kaddish.

“We arranged for Allen and the party to stay at the Britannia hotel in Didsbury as my flat was a little too small.”

Also reading at the event was Ginsberg’s long-time friend Peter Orlovsky and Anne Waldman.

According to Lama Jampa, Manchester’s Beat scene was in fact in full-swing long before Ginsberg visited the city in person.

He recalled a ‘quasi-Beat poetry scene between 1965 and 1968,’ and attended Manchester-based readings by British Beats such as Michael Horowitz and others who featured in Horowitz’s Angels of Albion anthology.

The importance of Wilshaw’s Bookshop on John Dalton Street near Deansgate was also highlighted, as it was the place where publications released by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s essential Beat press City Lights Publications could be accessed.

This combination of the wide-reaching influence of the Beat generation, the heritage of his guitarist and his occasional appearance in the city indicates that Ginsberg’s direct impact on and connection to Manchester is often under-appreciated.

Steven summarised Ginsberg’s ability to instigate cultural change: “If you were his friend, you had all these tags attached to you. This is Steven Taylor, composer, poet, watercolourist.

“You had to be part of this vast network of cultural activism he was constantly spinning. You couldn’t not be important.”

Although he acknowledged that Howl is not as prevalent in the minds of young people as it once was, Steven said that the poem still has things to say that are applicable to society today.

He said: “Howl is still relevant because the post-world-war alienation of youth that Kerouac called “Beat” (meaning beaten down, ripped off) is still with us.

“Allen said that if you tell the real, deep truth about yourself, if you say the things that everyone feels but is afraid to say, then it will resonate with everyone.

“That’s what Howl did.”

In the 60th year since the first public reading of Ginsberg’s seminal Howl, it is worth paying attention to what the poem and poet had to say, and acknowledging its relevance to society and the underground culture that is around us today.

Images courtesy of John Lynch, with thanks